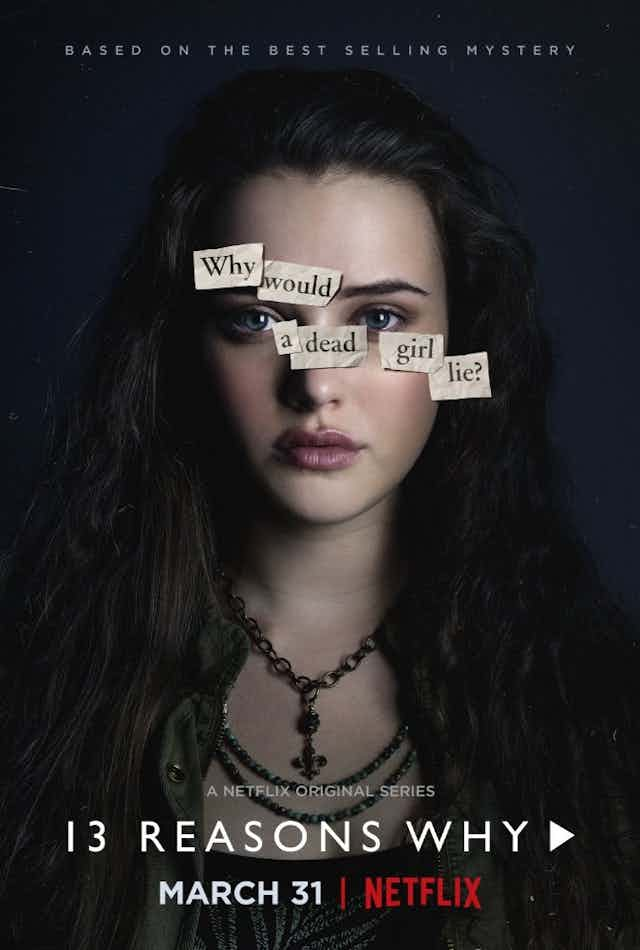

13 Reasons Why is a misnomer. There is only one reason in this “whydunnit” from Netflix. The miseries borne by its protagonist, Hannah Baker, and chronicled over the course of the narrative – bullying, slut-shaming, stalking, loneliness and gossip – are nothing when compared to the rape that “breaks her soul”. It is the reason for her suicide.

Or at least, it is the reason as presented by a show that seems more interested in how it tells its story, than in its psychological realism. As has already been pointed out, one of the show’s most problematic features is that it presents suicide as a rational, if extreme, response to external forces, rather than as a product of acute mental distress.

Each episode is structured around a side of a cassette tape recorded by Hannah before her death. Each tape is addressed to a different person, with the now heavily parodied: “Welcome to your tape”, launching an explanation of the harm the addressee caused Hannah.

But the cumulative force of these injuries – and the implication that her suicide was a result of “one thing on top of another” – is belied by the rape in episode 12 (or “Tape 6, Side B”). “In that moment”, as Hannah said on the tape, she “had felt like” she “was already” dead. Indeed, it is previously suggested that her other hardships are all things that she might have lived with.

We have heard this story before. The twinning of rape and suicide – and further, of rape with a death that anticipates bodily destruction – is a classic scenario.

Lucretia

It is a pattern followed by one of the most famous rape victims of antiquity: Lucretia. Her story, recounted in Livy’s compendious Roman History (c.25BC), tells of how Sextus Tarquin, son of the Roman king, tries to seduce Lucretia. Finding her unwilling, Tarquin threatens to kill her and a male slave, swearing to place their bodies together so that it will look like Lucretia had committed adultery. Livy writes that rather than endure this “dreadful prospect”, Lucretia’s “resolute modesty was overcome” by Tarquin’s forceful and “victorious lust”.

The next day Lucretia explains to her father and husband what had befallen her and, after imploring the men to avenge her, stabs herself to death. In the tale, her family carries Lucretia’s body through the streets until the citizens, enraged by the sight of her, rebel against the Tarquins and banish the king, founding the Roman republic.

Another early account, Ovid’s Fasti (c.8AD), describes how Lucretia’s male relatives returned to find her preparing her funeral. This detail, memorably recalled in Chaucer’s The Legend of Good Women (c.1386) when Lucretia is asked by her attendants for whom she is in mourning, serves to reinforce the idea that Lucretia is, in effect, already dead – her suicide is a formality.

This impression is made explicit in Shakespeare’s narrative poem, The Rape of Lucrece (1594), when the matron declares her soul to be polluted and chained with “wretchedness” after Tarquin’s attack – her suicide is presented as a means of preventing the spread of this contamination. Shakespeare was to return to this theme in Titus Andronicus and Measure for Measure.

In the mid-18th century Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa (1748) used the Lucretia story to analogise its heroine and her evocatively named rapist, Lovelace. After the rape that forms the novel’s central action, Clarissa, too, declares her soul to be divided and warring within her before making a welcome, even willing, embrace of death.

Victim shaming

The overwhelming impression in each of these narratives is of rape as a violence that attacks the mind or spirit as well as the body, and of suicide as an inevitable – even logical – response to this violation.

But part of what is so insidious – and so disturbing – about this pattern is the culture of the victims’ shame, rather than the attacker’s guilt that seems to drive these actions. It is they, and not their rapists, who are dishonoured by the violence.

We see this misogyny firmly on display in the 21st-century in 13 Reasons Why. It is the reason why the counsellor Hannah consults hours before her suicide tells the teenager to “move on”. It is the reason her rapist declares that “every girl in the school wants to be raped”. It is the reason that reports of the sexual assault of a young woman at Stanford University in 2016 regularly referred to her attacker’s swim times as some kind of mitigating evidence, repeatedly calling him a swimmer rather than a rapist.

For Hannah, if this culture is not going to change, she’d “better get on with it”. Determining that “no one would ever hurt” her again, she hurts herself. Her suicide is, on the face of it, an act of revenge, a call to arms that highlights the leniency of a malignant culture that is detrimental to the physical and emotional well-being of any person who might in any way inhibit it.

But, in marking her rape as the turning point on her road to suicide, in presenting her death as the actualisation of a murder that has already taken place, the show does more to uphold the misogyny it purports to revile than repudiate it. Hannah neither outlives nor survives rape. Like Lucretia, her rape becomes a story presided over and disseminated by men. There should be no reason for any of this.

The Samaritans can be contacted in the UK on 116 123. Papyrus is contactable on 0800 068 41 41 or by texting 07786 209 697 or emailing pat@papyrus-uk.org. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Hotline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is on 13 11 14. Hotlines in other countries can be found here.