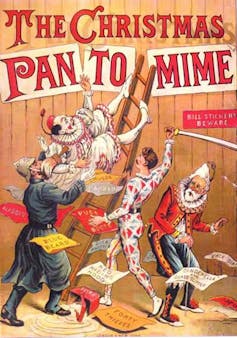

It’s the time of year when drag collides with family entertainment. Yes, the British pantomime season is upon us, complete with all its bizarre conventions and creative casting. Among the ex-soap stars, reality TV veterans and retired sporting heroes will be a small band of middle-aged men who have cornered the market in that pantomime staple, the Dame. They will portray grotesque caricatures of women and deliver lines filled with sexual innuendo – all for the amusement of children (and, sometimes, their parents).

In her latest Prima magazine column, actress Caroline Quentin has questioned this practice.

I wonder why, in progressive 2016, we still like to see men dress in drag for entertainment… Is it appropriate, in this age of inclusion, for middle-age women to be ridiculed by blokes in skirts and too much make-up?

A reasonable question to ask, though one whose implications might not be welcomed on the drag circuit – where blokes putting on skirts is rather the point. And besides, the “tradition” of the pantomime dame is about much more than just cross-dressing.

‘Oh no he didn’t’

The role came about in the early 19th century, developing from the “travesti” tradition of theatrical cross-dressing. Early masters (mistresses) of the role, included Dan Leno who, like many of his successors, came more from a music-hall tradition, rather than a dramatic one.

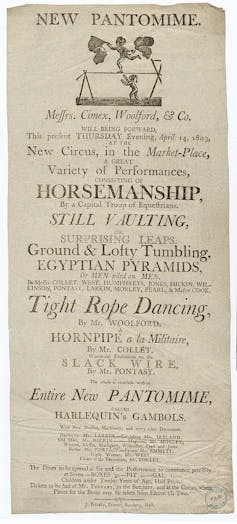

By Leno’s time, pantomime –in one form or another – had already been established for at least a century – first as a performance known as a “harlequinade” using stock characters drawn from the Italian “commedia dell’arte” a tradition of masked, slapstick comedy. These performances were wordless, as the theatres where they were played were unlicensed to stage spoken drama. And it is this silence that put the “mime” into “pantomime”.

Of course, over the years some conventions of the traditional pantomime have faded – such as the casting of the “principal boy as a girl” – having proved about as useful as a pantomime horse.

This faded tradition came about in part because of the novelty that came from seeing the legs of a girl in tights – a “breeches” role – rather than in the modest skirts that women were normally restricted to at the time. And as times have changed – with people more used to the sight of legs – the principal boy became less relevant to a world of panto. Modern conventions of pantomime, such as the inclusion of fairy tales, audience participation and comic use of cross-gender casting have all become staple parts of what many see as the traditional family panto.

‘Oh yes he did’

But while Quentin may well be right when she says the casting of a cross-dressing pantomime dame is less relevant in a world that has begun to accept that women can be funny in their own right, the idea of cross-dressing and transgressive gender portrayals on stage are much longer traditions – as old as theatre itself.

From the ancient Greeks, through to Shakespeare and into the 17th century, men or boys played all the female roles. And until today, drag has remained a staple of comedy – from burlesque to mainstream entertainment.

While most of that has seen men dressing as women, the tradition of the drag king – women dressed as men – also dates back to the 18th century and was commonplace at the time in music halls. This has been a key component of the contemporary burlesque revival, which has seen drag king groups formed and performing across the UK.

Ultimately, theatre has always been a space where gender roles and sexual identity are questioned, mocked or unsettled –the stage offers a safe space to view fluid gender identities.

In contemporary theatre, important progress is being made in casting for women. That most traditional of Christmas shows, Peter Pan has transferred from Bristol Old Vic to the National Theatre in London. Director Sally Cookson presides over a cast with a male Peter Pan (no breeches casting here), a male Tinkerbell and a female Hook. And, just down the road at The Old Vic theatre, Glenda Jackson has achieved a triumphant return to the stage as King Lear.

So perhaps the future casting possibilities for women are not quite as bleak as they once were. And with an increase in “gender-blind” casting, it might well mean that when it comes to sexism on stage: “It’s behind you!”