In awarding the 2017 Archibald Prize to Mitch Cairns’s portrait of his partner, Agatha Gothe-Snape, the trustees have reaffirmed a tradition of artists painting artists that began with the very first prize in 1921 (awarded to W.B. McInnes’s portrait of Desbrowe Annear).

In the following years, quite a few self portraits have won, but the only other time an artist has kept it in the family, so to speak, was Janet Dawson’s portrait of the writer Michael Boddy (winner in 1973). Cairns’s portrait is a delightfully intimate work, celebrating the relationship while making a playful nod to Gothe-Snape’s own experimental sculptural installations with the treatment of the window in the rear.

The radical shift in this year’s competitions is the reaffirmation of the power of the artists from the APY lands, in the very heart of the country. Last year, the five Ken sisters won with Seven Sisters.

This year the Wynne took over the main room in the Art Gallery of New South Wales to give a stunning display of paintings by APY land artists, while Tjungkara Ken’s self portrait, Kungkarangkalpa tjukurpa (Seven Sisters dreaming), was a finalist in the Archibald.

The Wynne winner, Betty Kuntiwa Pumani’s Antara, is hung high, to preside over the room like a benign spirit. The Wynne was first awarded 120 years ago, at a time when Australian Impressionism was the dominant style – and Aboriginal culture was not highly regarded.

Betty Kuntiwa Pumani and her sister Ngupulya gave their speech in language, translated for them by a young colleague. At the end of the speeches, after they stepped down from the dais, Sally, the translator, threw her arms in the air in triumph – it was one of the great moments in the history of the prize.

The third prize in the gallery’s annual festival of community engagement is the Sir John Sulman Prize. Unlike the others, which must by law be judged by the trustees, the Sulman – awarded for genre or history painting – is judged by an artist.

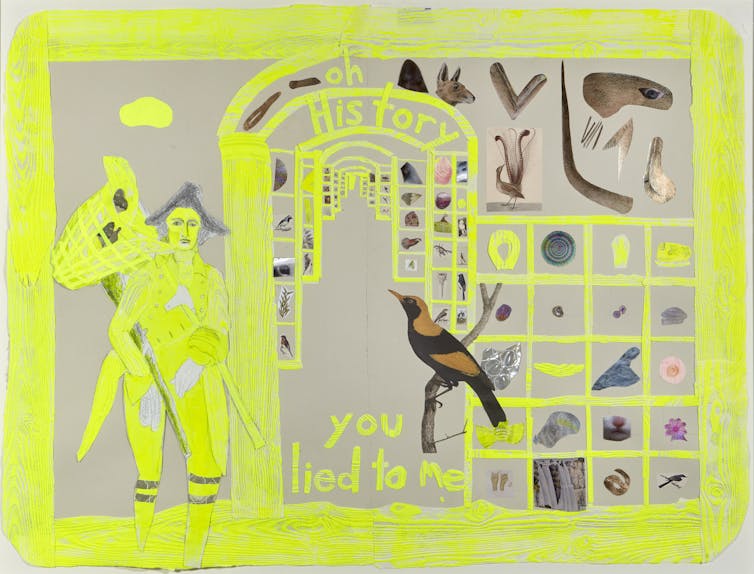

Tony Albert, an Archibald finalist, gave the prize to Joan Ross’s Oh history, you lied to me. This is a clever continuation of Ross’s ongoing critique of colonisation as seen through reworkings of images of the past.

She sees history as “an unfaithful lover”, lying and betraying even as it collects objects from the past. In this case, she has reworked a figure from Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews and created a fictional version of the Leverian Museum that holds relics from Cook’s voyages. This is in the form of collages in a variety of shapes.

Someone at the gallery has kindly written captions designed to entice children into looking at the art in the competitions. This is a commendable policy and, along with the Young Archie, is a sign that the gallery is concerned with encouraging a future generation of artists and art lovers.

In the case of Ross’s work they may wish to reconsider the advice to “List the animals and objects you recognise in this artwork”.