Those debating Australia’s future, and its immigration policy would do well to consider a lesson from the past. Anybody can establish a successful state, the real difficulty is maintaining its success. And the key to that is extending citizenship to those who need it.

In the short period of its empire, Athens practically invented western culture. It is impossible to imagine what drama, philosophy and history-writing would look like without Athens. Even after the loss of its empire, it remained home to some of the finest minds that the Greek world produced.

Historians of the classical world are often struck by the longevity of the Roman Empire and the comparative brevity of its Athenian counterpart.

The strength of the Empires

Depending on where you place its start, the Roman Empire lasts for between 500-800 years.

In contrast, the Athenian Empire is sporadic. At best, it controlled the Aegean for approximately 100 years and even then its influence was often weak and partial.

Explaining the difference is difficult. The answer doesn’t lie in military might.

Roman legions are impressive, but then so too was the Athenian fleet. Athens ruled the waves with exactly the same level of control as the Spanish and British would do centuries later.

Moralists like to blame moral decay for the fall of empires. There is actually no evidence to support the correlation between debauchery and loss of political power, but even if it were true, few would argue that Athens was more debauched or decadent than Rome.

Citizenship of the Empires

There is, however, one vital difference between Rome and Athens: its citizenship policy.

Almost from the very beginnings of its Empire, Rome extended citizenship to its conquered peoples. The rate of grant of citizenship is not consistent, but ultimately every nation ended up as citizens of the Roman Empire.

In contrast, Athens jealousy guarded its citizenship. Large block grants of citizenship are practically unknown. We know of only two exceptional cases.

The paradox about Athens is that, thanks to its democracy, Athens knew the tremendous benefits that came from opening up the city.

By allowing its citizens to run the State, Athens avoided the civil wars and demands for redistribution of wealth that plagued other ancient cities.

Athenian democracy was unique in the way in which it extended power to all members of the citizen body irrespective of wealth or birth.

The city was so committed to the notion of equality of opportunity that it even decided that the majority of positions in its government should be awarded by lot rather than election. Elections unduly favoured the wealthy and educated, the Athenians argued, and for this reason should be avoided.

A representative democracy?

It’s an argument with a certain logic. Athenians would have looked round at our contemporary parliament with its overrepresentation of lawyers and felt justified in their suspicions about the fairness of the electoral playing field.

Yet, this generosity had limits. If you were a slave, foreigner, or a woman, the city offered you little.

It might have staged the finest tragedies, but women weren’t invited to attend and those foreigners that did attend were treated to a preliminary spectacle of Athenian self-congratulatory gloating as the latest tribute from the Empire was paraded before the theatre audience.

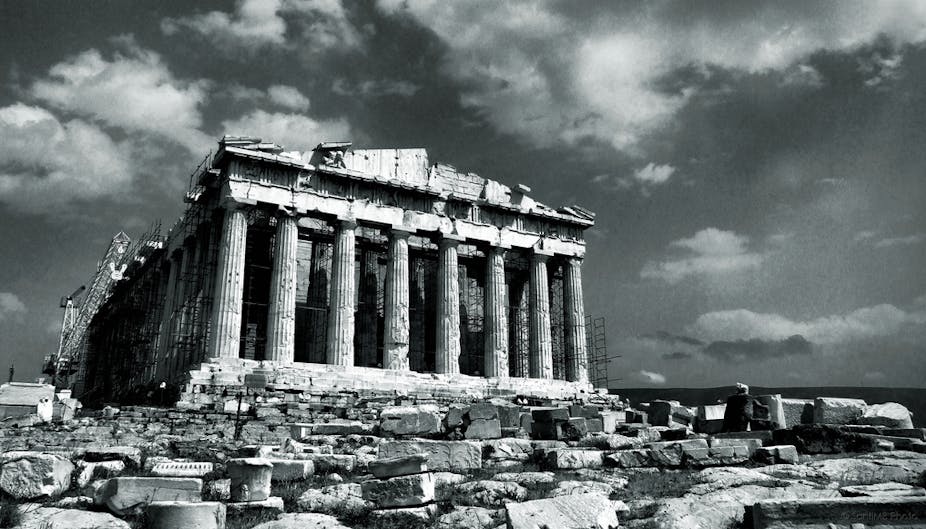

When members of the Athenian Empire came to Athens, they didn’t see the magnificence of the Parthenon as we do today. Instead, they saw a building in which they had no part, a squandering of their money to beautify a city that constantly sought to ridicule and exclude them.

An exclusive Empire

Given such a situation, we can see why member states of the Athenian Empire were only too happy to welcome any outside power that would free them from the Athenian yoke. There was little to bind them to their imperial rulers.

Foreigners went to Athens to make their fortune, not to find a home. Moreover, it meant that when rivals to Athens arose there was little to keep the best and brightest in the city.

Having its army destroyed by Philip of Macedon was certainly a setback for Athens, but what really finished off Athens was the tremendous success of the cosmopolitan cities of Alexandria, Pergamon, and Antioch that were created by Philip’s son, Alexander the Great and his successors.

In their multi-cultural melding of ideas, they offered a radically different and extremely attractive alternative to the exclusive city-state.

Athens’ leaders once boasted that it was the “educator of Greece”. Yet ultimately their mean-spirited, xenophobic attitudes would see Athens put at the bottom of the class.