Energy upgrades in Australia’s buildings could deliver a quarter of Australia’s 2030 emissions reduction target. Improving energy performance through improved building design, heating and cooling systems, lighting and other equipment and appliances could also deliver more than half of our National Energy Productivity Target.

Progress has been slow, however, and our research shows that delay leads to lost opportunities and billions in wasted energy costs.

The new federal environment and energy minister, Josh Frydenberg, has an opportunity here to demonstrate the potential of his new merged role. Today in Canberra, Australia’s energy ministers are meeting for the first time since the election through the COAG Energy Council.

One item on the agenda will be the National Energy Productivity Plan (NEPP). It aims to improve energy productivity 40% by 2030. This involves increasing the economic value produced from each unit of energy consumed.

The NEPP contains a number of good measures relating to buildings. However, without stronger governance arrangements, more transparency and stronger and clearer public communication and engagement, there is a risk that these policy measures will simply slip between the cracks of multiple agencies, portfolios and jurisdictions in the building sector.

What can better buildings achieve?

Our research found buildings could help meet our climate and energy goals, as you can see in the charts below.

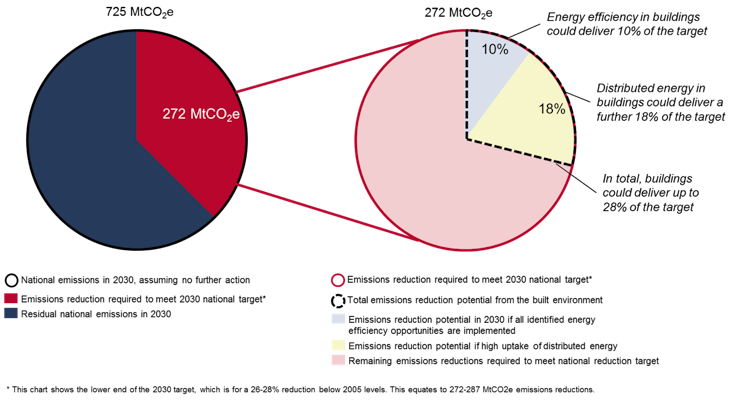

We found that improving energy efficiency in buildings could deliver 10% of our emissions target. Distributed energy (primarily rooftop solar) could achieve an extra 18%.

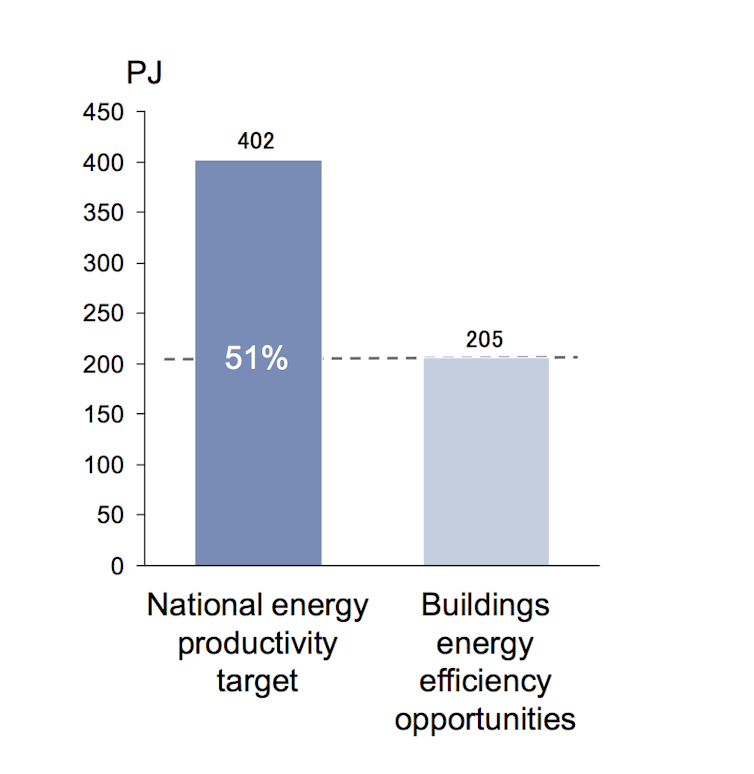

The energy efficiency improvements could reduce energy use by 202 petajoules, or half of what would be needed to achieve the energy productivity target.

The cost of delay

Despite the massive opportunity to reduce emissions from the building sector, overall progress to date has been slow.

Market leaders, particularly in the commercial office market, have achieved a radical change in their energy productivity and are recognised as global leaders in sustainable buildings. There are many examples of very high-performing or net-zero-emission buildings around Australia.

However, the market as a whole has improved its energy performance only 2% over the past decade for commercial buildings, and 5% for residential buildings. We are not currently on track.

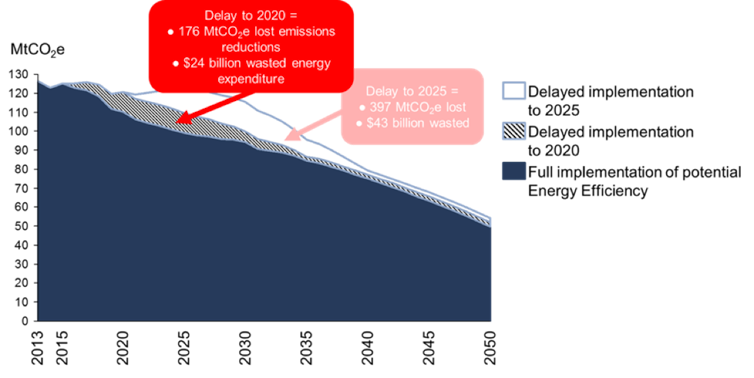

Our report found that continuing to delay action to reduce emissions from buildings means we would lose a substantial amount of cost-effective options to improve energy performance. Many emissions reduction opportunities exist only for a certain period of time. For example, installing inefficient equipment instead of more efficient options effectively locks in excessive emissions for many decades into the future.

Just five years of delay could lead to A$24 billion in wasted energy costs and more than 170 million tonnes of lost emissions reductions by 2050. This is a very substantial loss, considering the current national emissions target aims to reduce emissions by 272 million tonnes by 2030.

Without additional action buildings would eventually consume more than half of Australia’s “carbon budget” by 2050. That would leave less than half for all other sectors of the economy, including emissions-intensive industries, transport, land and agriculture.

Stronger policy

To realise the emissions reduction potential in the building sector, strong policy will be required to tackle the barriers to better energy performance for buildings. Our report recommended five key solutions as part of an integrated policy suite.

First, develop a national plan to co-ordinate policy and emissions-reductions measures to extend gains made by market leaders across the entire building sector.

Second, introduce mandatory minimum standards for buildings, equipment and appliances aligned with the long-term goal of net zero emissions.

Third, develop incentives and programs to motivate and support higher energy performance in the short to medium term.

Fourth, reform the energy market to ensure it supports cost-effective energy efficiency and distributed energy.

Finally, we need a range of supporting data, information, training and education measures to enable informed consumer choice and support innovation, commercialisation and deployment of new technologies and business models.

Implementing these policy measures would set Australia on a pathway to zero-carbon buildings and unlock the large potential for buildings to deliver improved health outcomes and more liveable and productive cities.

Unblocking barriers

Unfortunately, the opportunity to reduce emissions from buildings is blocked by strong barriers that require co-ordination between the Commonwealth, states and territories.

To address the complexity of this task, the NEPP needs stronger governance arrangements, including a specified target or targets for buildings, to complement the overall 40% NEPP target, and more regular public reporting (there is no public review until 2020).

Stronger and clearer communication and engagement around the target and buildings’ energy performance within it would also help provide confidence and drive innovation and activity among households and businesses.

In addition, we need better co-ordination between the members of the Energy Council, and between the council and other government forums and agencies.

For example, the National Construction Code, which regulates minimum standards for new buildings and major refurbishments, is a critical policy lever. However, the code is overseen by the Building Ministers Forum, not the Energy Council, while a range of different state and territory bodies oversee enforcement of the standards.

There are similar issues around harmonising of different energy performance ratings across jurisdictions, co-ordinating training and accreditation of professionals throughout the building design and construction sector, and energy market reform to establish a level playing field for energy efficiency and decentralised renewable energy.

Co-ordination of these issues should be a major focus for the Energy Council. The new minister for environment and energy – as the minister responsible for delivering on both our national emissions reduction targets and on the productivity plan – is now in a unique position to lead these efforts. We encourage the COAG Energy Council to support him in this.