Australia has just had its hottest October, and we can already say that human-caused climate change made this new record at least ten times more likely than it would otherwise have been.

But if we turn our eyes to the past, what role did climate change play in the broken records of 2014? Last year was the hottest on record worldwide, and came with its fair share of extremes.

As part of the annual extreme weather issue of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society released today, five papers by Australian authors including us, investigate the role of climate change in extreme weather in 2014.

Year of records

Australia was hit hard in 2014 (although perhaps not quite as hard as 2013, which was Australia’s hottest year ever).

The year started with a bang when the international spotlight fell on southeast Australia as Melbourne was baked by the infamous “Australian Open heatwave”. It led into 12 months that saw the country experience a 19-day heatwave in May, the hottest spring on record, and unusually hot weather in Brisbane during November, right in the middle of the G20 World Leaders Forum.

In August, a record high pressure system stalled to the south of Australia and brought some unusual winter weather, including severe frosts.

So did human-caused global warming play a role in this “weirding” of Australian weather?

Revealing the role of climate change

The annual extremes issue centres on one of the fastest developing areas in climate change research, the role of climate change in recent extreme weather events.

While the link between human activities and climate change has been firmly established for several decades, attributing a single event to human influence isn’t easy. This is because individual events may be the result of natural climate variation.

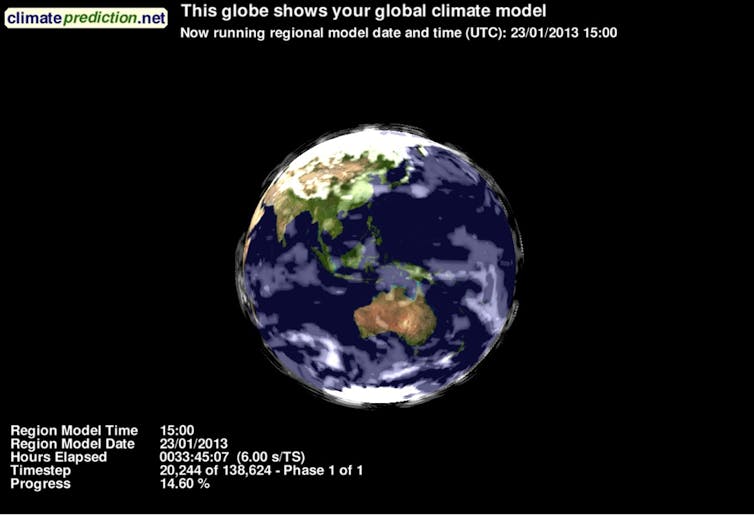

To get to the heart of how climate change is influencing these extreme events, scientists try to determine how much more likely individual extremes are as a result of climate change. Using climate models they compare the world of today with a parallel world without human greenhouse gas emissions.

These scenarios are often run on models thousands of times in an effort to recreate events that are of a similar scale. By comparing the results of modelled climates with and without human-produced greenhouse gases, researchers can determine how much more likely it is that an extreme weather event occurred as a result of human-caused global warming.

This approach is similar to the way epidemiologists investigate whether smoking increases the likelihood of lung cancer.

Interestingly, there was a significant citizen science role in three of the Australian peer-reviewed studies reported in the extremes issue. Using a large number of climate simulations run on thousands of home computers as part of the Weather@home project, the scientists were able to examine local-scale extreme events such as the January heatwave in Melbourne.

What we found

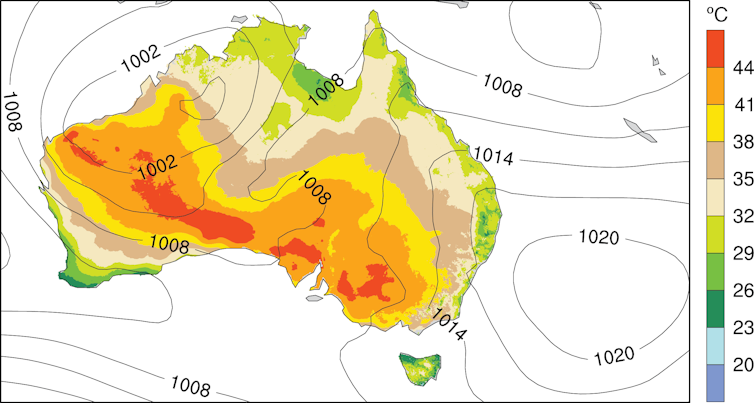

The first study, led by Mitchell Black, focused on the prolonged heatwave in southeast Australia in January 2014. During this event Adelaide recorded five consecutive days above 42°C (13–17 January) while Melbourne recorded four consecutive days above 41°C (14–17 January) during the Australian Open tennis tournament.

This study found that human influence very likely increased the chance of prolonged heatwaves in Adelaide by at least 16%. Meanwhile, the influence for Melbourne was less clear.

The second study, led by Andrew King, examined an extreme temperature event caught in the spotlight of international media attention - the unseasonably hot weather in Brisbane during the G20 summit in mid-November. While the hot temperatures were not record-breaking in Brisbane at this time, they were well above average.

This study found that human influence increased the likelihood of hot (above 34°C) and very hot (above 38°C) November days in Brisbane by at least 25% and 44%, respectively.

The third study, led by Michael Grose at CSIRO, examined the exceptionally high surface pressure to the south of Australia during August 2014. This was associated with severe frosts in southeast Australia, lowland snowfalls in parts of Tasmania, and reduced rainfall in the southern parts of both Australia and New Zealand.

The findings suggested that the likelihood of these pressure anomalies had roughly doubled due to human-induced climate change.

The remaining two studies published today used independent sets of climate model simulations.

The fourth study, led by Sarah Perkins-Kirkpatrick from the University of New South Wales, investigated the late-autumn heatwave (May 8-26) that resulted in Australian-averaged maximum temperatures being 2.52°C above the monthly average. Although this heat event occurred during the cooler months, events of this nature are important because they can affect agricultural productivity through changing crop cycles.

The study found that this kind of cool-season heatwave was 23 times more likely as a result of increased greenhouse gasses.

Pandora Hope from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology led the final study, which examined Australia’s hottest spring on record. The study concluded that the record heat would likely not have occurred without increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide over the last 50 years working in concert with anomalous atmospheric patterns.

Year on year, in the extremes issues and through various other investigations reported in the peer-reviewed literature, these attribution studies continue to show that climate change is no longer something that will occur in the future. The rise of human-caused global warming is here, now, and it is already causing changes to extreme weather events that we can see and feel.