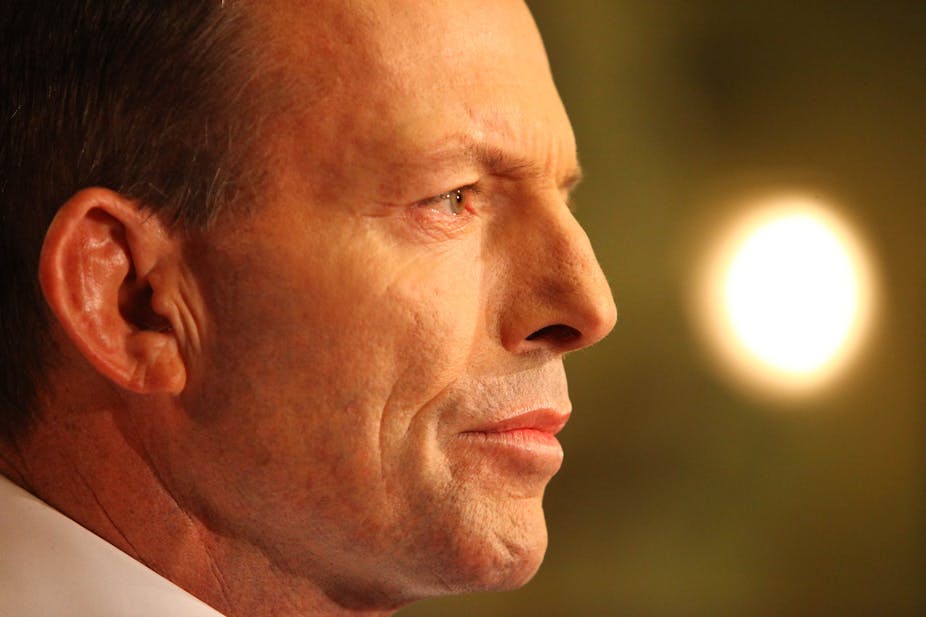

Opposition leader Tony Abbott has given Australians a “blood oath” promise that if the Coalition wins power at the next election, he will repeal the carbon tax within his first month in office.

But is this possible? And how would it work? Associate Director of the ANU Centre for Law and Climate Policy, Andrew Macintosh, explains.

Repealing the carbon tax is simple in theory. Assuming the Coalition forms government at the next election, it would introduce a series of bills, or even a single bill, that repeals the legislative scheme. Once the bills were passed by both Houses of Parliament, and the bills received the Royal Assent, the carbon pricing scheme would be a thing of the past.

A number of people have raised the potential – if the legislation was repealed – for there to be an acquisition of property issue under section 51(xxxi) of the Constitution. The argument is that this provision of the Constitution could frustrate a future Coalition government’s attempts to terminate the scheme. This is a furphy.

In order to activate section 51(xxxi), the Commonwealth, or somebody else, has to acquire property of some description, and that’s not going to occur in these circumstances. The proprietary interests associated with carbon units would be extinguished, but extinguishment is different from acquisition.

So the repeal of the carbon pricing scheme is likely to hinge on whether the Coalition can get the numbers in both Houses of Parliament, and the practicalities of unravelling a complex regulatory scheme. Any legal issues are likely to be of secondary concern.

What political scenarios does the Coalition face?

The numbers and the politics could go one of three ways.

First, the Coalition gets control of both the House and Senate at the next election. If this occurs, the Coalition would presumably wait until the new Senate is formed and then commence the legislative process to repeal the scheme. Although this is the cleanest scenario, it would still mean that the carbon pricing scheme would operate until 2014, possibly 2015. By then, a lot of the opposition to the scheme may have dissipated.

The second is that the Coalition wins office but does not take the Senate, and Labor accepts that the new government has a mandate to repeal the scheme. The Gillard government currently maintains that it will not agree to this. However, things could change if Labor experiences a 1975-style defeat at the polls in 2013; a new leader may feel they have no choice but to back down.

The third scenario is the same as the second, only Labor refuses to support the terminating bills in the Senate. This would leave the Coalition with one option if it wanted to completely repeal the scheme: a double dissolution election.

This has rarely been done and history suggests that governments that go to double dissolution elections tend to get punished for it. So it would be a big call for a Coalition government, which has been out of office for six years, to go down this path.

What other options would Abbott have to weaken the carbon tax?

Another option that a new Coalition government would have is to keep the carbon-pricing scheme in place but terminate the “fixed charge period” and remove the price floor.

In the first three years of the carbon-pricing scheme, there’s a fixed price that starts at $23, and after three years it goes to a standard cap-and-trade emissions trading scheme, where the market will determine the price. The only qualification is that over the period 2015 to 2018, there is meant to be a price floor, starting at $15, and a ceiling price set at $20 above the international price.

In order to reduce the financial impact of the scheme on polluters and households, the Coalition could go directly to a flexible price. The attraction here is that the international carbon price is currently very low (around A$5 per tonne) and it’s expected to remain subdued for an extended period. As a result, moving straight to a flexible price with no price floor would mean the impacts would be negligible.

Strictly, Abbott might claim this approach is in keeping with his pledge to axe the tax; after all, he would be getting rid of the tax (the fixed price period) and leaving an emissions trading scheme. While possible – and many people in Canberra believe it is probable – I personally think it is unlikely. Abbott would be setting himself up for the sort of criticism John Howard received when he was Prime Minister, and that Julia Gillard suffered when she did an about face on carbon pricing.

A more likely scenario is that Labor ditches the price floor prior to the election, in an attempt to appease the business lobby.

What would some of the flow-on effects be if Abbott succeeded in repealing the carbon tax?

As we all know, the carbon tax has been accompanied by major changes to the tax system: the tax-free threshold has been raised to A$18,200 and keeps rising after that. There are also increases to pensions and family tax benefits. The Coalition has said – and I’ve heard Joe Hockey say this – that they intend to wind all that back. I’d imagine that’s going to be pretty unpopular.

There’s also quite a lot of monetary compensation going out under the scheme – to coal-fired generators and gassy coal mines. So that would also presumably have to be unwound. Importantly, if contracts have been signed for the provision of any of this money, the Commonwealth will have no way out. It will have to pay the money, even if the scheme is terminated.

How would a repeal of the tax affect big business?

In theory, it’s simple: they stop buying and surrendering carbon units. However, in practice, things are likely to be more difficult. Many businesses will have made arrangements to manage their carbon liabilities, including by establishing compliance systems, signing contracts to hedge their exposures, and commencing offset projects under the Carbon Farming Initiative.

Some businesses may have made investments on the expectation of an ongoing carbon price, for example, in gas-fired generating assets. Unwinding many of these arrangements will be difficult, involving significant costs.

Due to the cost and inconvenience, I would imagine that, in a couple of years, many businesses will be opposed to the repeal of the scheme and the Coalition could face a backlash if it proceeds with its plans.