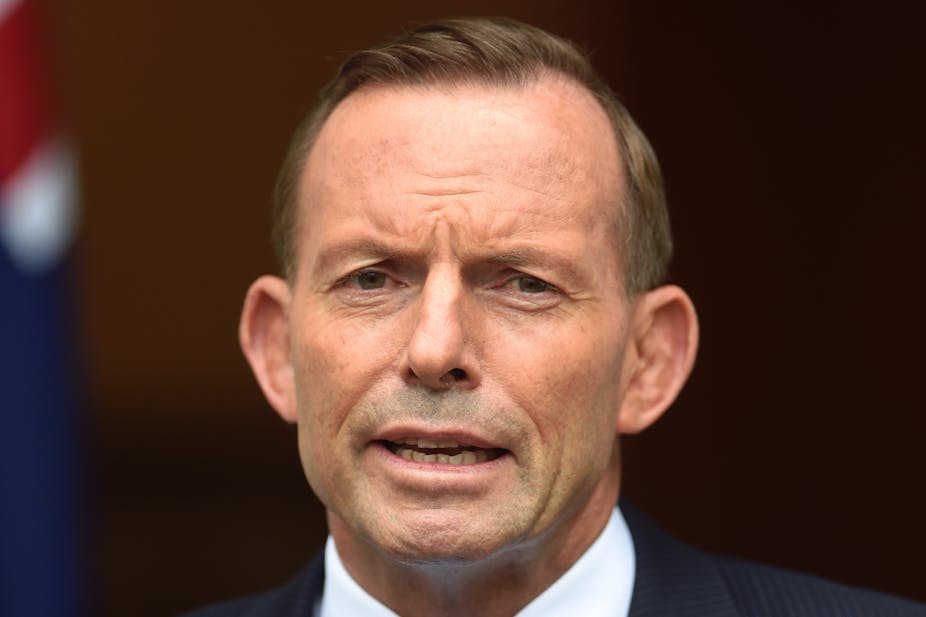

Tony Abbott is precariously perched on icy slopes – deeply unpopular both in the community and with his backbench.

More slips and/or continued disastrous polling would plunge him to political death, while the way to safer ground is difficult and there’s widespread doubt that he’s equipped to get there.

After a vote that clearly shook him (some 40% of his colleagues backed a spill) Abbott admitted to his party room he’d had a “near death experience”.

Cross-currents were at work in the vote. Critics, especially unnerved by the Queensland state result, had reached the end of patience with their out-of-touch leader. While the 35-member frontbench mostly (though not entirely) supported Abbott, the backbench was strongly in favour of a spill.

The counter-current was the pull of the “fair go” – the feeling Abbott should be given more time to attempt to revive.

The cost of leaving him in place is to invite a period of limbo while the Liberals judge his performance. In that, the prime metric will be the polls. The odds are against a leader as unpopular as Abbott remaking his image.

Speaking to his MPs, Abbott reiterated new arrangements for greater consultation with backbenchers and the full ministry and less interference by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) in ministerial staffing and other matters. Policies would be better road-tested and a more pragmatic approach taken to the Senate, he told them.

On the vexed Medicare changes, Abbott later said while “obviously we have some proposals which are out there already”, he had told the party room “there would be no new proposals come forward without the broad backing of the medical profession”. The future of the scaled-back Medicare co-payment remains unclear.

It seems to have taken until now for Abbott to start to appreciate his parlous position, or the depth of backbench frustration. And what he said on Monday suggests he still doesn’t fully grasp the extent and implications of the rebuilding job.

Abbott told his news conference that last year’s budget was “too bold and too ambitious”, but he’d listened, learned and changed and “and the government will change with me”. In future, “we will not buy fights with the Senate that we can’t win, unless we are absolutely determined that they are the fights that we really, really do need to have”.

If the government’s policy approach is to be less harsh, more politically sensitive, how is that to be reconciled with the challenge of budget sustainability? What is to be the new story about its commitment to reform?

Ahead of a meeting with chairs of backbench committees, Abbott aired his new mantra – that “this is going to be a government which socialises decisions before they’re finalised”.

The risk is the government goes from one flawed approach to another. It consulted too little, but if it falls into a lowest common denominator approach to policy, it will be seeing off any meaningful reform agenda – assuming that was not stillborn already.

It could easily find itself caught between a poll-driven, muscled-up backbench and the tough demands of an uncompromising business constituency.

The Business Council of Australia after the vote called for “traction on increasingly urgent policy changes” including “a sensible, strategic approach to repairing the federal budget, a more competitive tax system, the removal of unnecessary, unwieldy red tape and a more flexible workplace relations system”. These causes are more likely to be rapidly losing traction, given Abbott’s changed political circumstances and an uncertain economy.

On another front, there remains the irritant of Abbott’s personal office; it has rankled ministers and backbenchers and been a factor in the swell of leadership discontent.

Chief of staff Peta Credlin has recently become less visible and intrusive, but is still in place.

Credlin’s defenders argue she’s done a good job; Abbott gives her huge credit for getting him where he is now.

But staff must be judged by outcomes: if your actions have helped put your boss’s future on the line, you’ve flunked the test. The PMO should make a fresh start, minus Credlin, but that seems a step too far for Abbott.

Abbott was asked at his news conference whether he retained confidence in Treasurer Joe Hockey. He dodged, saying that “all of us are determined to lift our game”. Later, under Labor questioning in parliament, he said: “I stand by my treasurer”.

Hockey has failed on substance (the budget’s content) and salesmanship (including his confrontational language – “lifters and leaners”, the “age of entitlement”).

But Abbott and Hockey are conjoined – the prime minister, particularly but not only by his cavalier attitude to trust, shares ownership of the budget debacle.

Decoupling from Hockey would likely only worsen Abbott’s problems. It would be a refusal to accept joint responsibility.

Unless, however, Abbott can make sure Hockey becomes a better “lifter” in the common cause – less bluster, more understanding of middle Australia – Abbott’s leadership will be further endangered.

If he wants motivation to improve, Hockey only has to look over his shoulder, where he’ll see the ambitious Scott Morrison, who’d be treasurer in a Malcolm Turnbull government.

In his attempt to regroup, Abbott needs as well to rebuild his relationship with his deputy Julie Bishop. Tensions between the two have mounted over Credlin’s role and other things. Bishop stood with him against the spill. But she made it clear she was just doing her duty as deputy.

In the time ahead, he needs her more than she needs him. For Bishop, the grass would be as green on the other side of the leadership divide.

Abbott said on Monday night that he’d been telling colleagues: “I am a fighter. I know how to beat Labor Party leaders. I beat Kevin Rudd. I beat Julia Gillard. I can beat Bill Shorten as well. What I’m not good at is fighting the Liberal Party.”

What Abbott is also not good at is governing – and it is an art hard to acquire quickly when you’re being buffeted on those icy slopes.

Listen to the latest politics with Michelle Grattan podcast, talking the leadership spill with Federal Director of Barton Deakin Government Relations, Grahame Morris, here.