In Salman Rushdie’s 1988 novel The Satanic Verses, the fictional character Whisky Sisodia comments that the “trouble with the Engenglish is that their hiss hiss history happened overseas, so they dodo don’t know what it means”. It is this complex and often unsavoury history – a history of conquest, dispossession, and violence – that Rushdie’s fiction attempts to make sense of.

Reading postcolonial literature not only makes us better readers and writers, it can also help us to better understand the history of British colonialism – warts and all. Indeed, it was this intimate relationship between literature and empire that the literary critic Edward Said articulated in his reflections on the worldliness of texts and his injunction to critics to speak truth to power. It is precisely such an understanding of British culture and history that the current political establishment would prefer us to forget.

Like his recent policy proposal to design a history curriculum for schools that nostalgically celebrates the achievements of the British empire, secretary of state for education Michael Gove’s move to focus the GCSE English literature on more British texts is a further sign of his postcolonial melancholia. It is a longing for Pax Britannica in an era of financial austerity and right-wing populism.

It is important to acknowledge that contemporary authors such as Meera Syal and Kazuo Ishiguro are represented under the heading of “Exploring modern and literary heritage texts” in the draft version of the OCR’s specification for its new English Literature GCSE. Yet the main focus of the set texts in the literature curriculum is Shakespeare and 19th century prose. Similar emphasis exists in other exam boards’ drafts, including AQA’s.

Gone from the OCR’s draft are Amy Tan’s Joy Luck Club and Athol Fugard’s Tsotsi, not to mention American books To Kill a Mockingbird or Of Mice and Men (texts that Gove has denied he wanted banned from the curriculum).

Amnesia about imperialism

If Gove’s ideas about British imperial history are amnesiac, he also seems to forget that English literature was always worldly. In a well-known essay on Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea, and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the literary critic Gayatri Spivak wrote that “it should not be possible to read 19th century British literature without remembering that imperialism, understood as England’s social mission, was a crucial part of the cultural representation of England to the English”. One might say the same about Shakespeare’s The Tempest – a play that stages the politics of colonial dispossession and cultural imperialism using the conventions of a courtly masque.

Reading English literature from the postcolonial world can help to shed further light on the ways in which narrative, genre and metaphor are implicated in Britain’s colonial history. It is no accident that Jane Eyre compares herself to a slave and a “suttee” [sic] in Charlotte Brontë’s eponymous novel.

Yet, as Spivak suggested, it is only by reading this novel in conjunction with Jean Rhys’ 1966 novel Wide Sargasso Sea that one can begin to identify the ways in which Jane’s narrative of upward social mobility is made possible by the spoils of empire. One of the striking achievements of Rhys’ prose was to evoke a Caribbean landscape and history that resisted the authority of the English language and called into question civilising myths of British imperial culture.

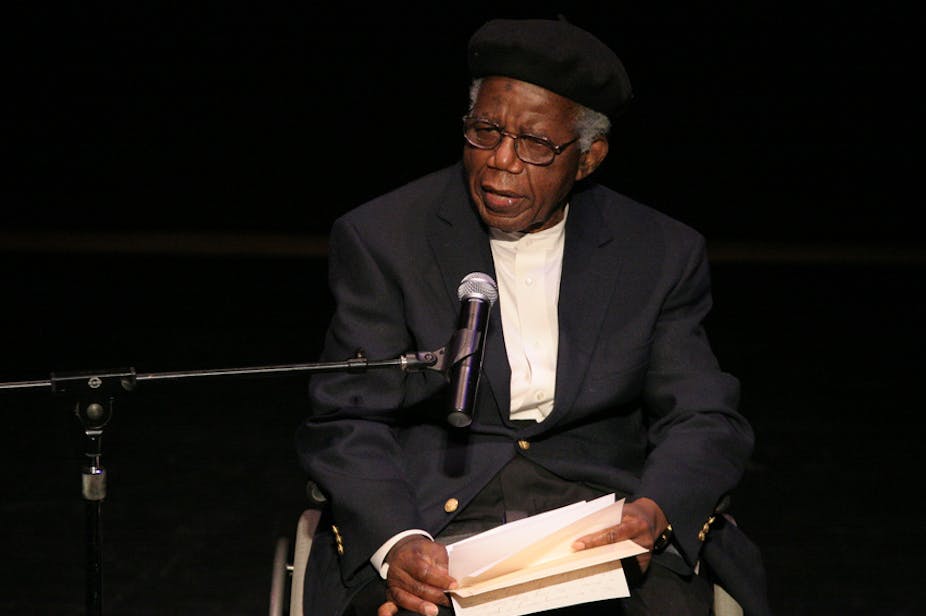

In a similar vein, the Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe used the formal conventions of narrative prose in novels such as Things Fall Apart and Arrow of God to register the complex society and history of Igbo life. He did so in a way that encourages readers to question the cultural stereotypes of African cultures that circulate in 19th century English literary texts such as H. Rider Haggard’s She or Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (a text which Achebe famously criticised).

Secondary school students, their parents, and most of all their teachers understand very well that a national English literature syllabus has always been shaped by the political agendas and interests of the powerful. What is perhaps less clear is the way in which reading literature should be both a critical and a worldly activity: one that encourages readers to think about literary texts in imaginative ways that speak truth to power.