Who Are We? This is the question that London’s Tate is asking at its free six day cross-platform event spanning the visual arts, film, photography, design, architecture, the spoken and written word and live art. The aim of the programme is to foster collaboration and exchange between artists and researchers, with a view to exploring what is becoming of the UK and Europe. How can “another we” be created, one less susceptible to the fear and suspicion currently dominating the continent?

The projects vary in scope and topic, from theatre to digital visualisation and from interventions such as redesigning the Union Jack to partaking in local acts of kindness. I myself am involved in a collaboration with the artist Bern O’Donoghue. Together, we have created an installation looking at the question of the “refugee crisis” and the question of migration.

Hostility to new arrivals and longer-standing immigrant communities is now rampant across Europe – not only in the UK, but also in Germany, Hungary and elsewhere. Fear predominates. People on the move are often viewed with suspicion on the part of “host” communities. Despite a broad range of political and social responses to the so-called European refugee “crisis”, a security-orientated concern with “foreigners” dominates public and political debate.

Meanwhile, efforts to construct different ways of talking about the issue appear to have failed to capture public imaginations. A humanitarian approach has been co-opted by the security agenda, such as when humanitarian organisations rescue people at sea only to deliver them to a detention regime.

Indeed, humanitarianism has been reproached from various angles as either “too soft” and idealistic, or as victimising people on the move in precarious conditions. Just consider Germany’s “open door” approach and you will see the difficulties of humanitarianism, particularly one that is so evidently pragmatic and self-interested.

As Miriam Ticktin has argued, humanitarianism is not simply compassionate. It also “hurts” people who don’t qualify as innocent and who are left at the whims of a compassion that can be fleeting. Alternative responses and ways of thinking about migration that are grounded in respect for each person or the dignity of all lives, including those rendered precarious through movement, need to be forged.

So who are we?

Many have tried to address the question of how to create such alternative approaches to migration or mobility in a theoretical manner. For example, the appeal to people on the move simply as human, as their European counterparts are, is one that has frequented debates in the midst of hostility over recent months and years.

Such debates are important, but how they can capture public imaginations in the midst of times dominated by fear and hostility is unclear. So O’Donoghue and I have taken a different tack, working together in this installation to provide tools for people to explore “who we are” and our relation to a “crisis” that has left many dead after seeking to travel to Europe by boat across the dangerous Mediterranean Sea.

Our installation and symposium is designed to provide opportunities to explore how different creative mediums and tools of interaction can enable a transformation in the ways that people respond to migration. Specifically, we want to explore the power of artistic creativity, dialogue, and story-sharing in opening up new ways for host communities to relate to people on the move in precarious situations.

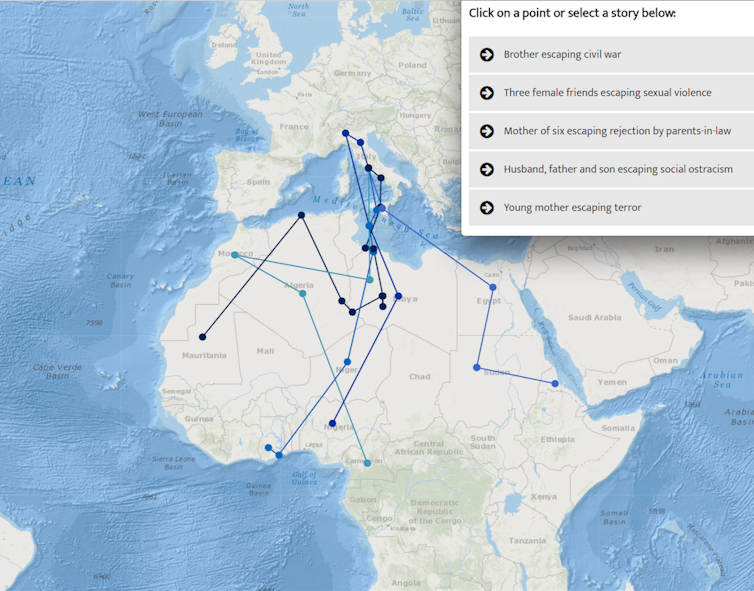

Our projects – O’Donoghue’s art installation, Dead Reckoning, and my story map, Crossing the Med, provide a new perspective on the journeys and experiences of people seeking to cross the Mediterranean sea by boat. While the projects are independent from one another, we have worked together to bring different tools by which people can reflect upon and have dialogue about a “migration crisis” that is characterised by many deaths at sea.

Dead reckoning/crossing the Med

I am also involved in a collaborative research project involving scholars from University of Warwick, University of Malta, and ELIAMEP, Greece. We carried out over 250 in-depth qualitative interviews with people who have attempted – or who have planned to attempt – the dangerous boat journey across the eastern and central Mediterranean sea routes.

The primary aim of this project is to assess policy effects on people on the move and to inform policy makers. But we are also concerned to inform wider public perceptions of migration, and to challenge the tendencies that are driven by fear and hostility.

Acknowledging the importance of sharing stories with people on the move, the story map we created for the Tate event enables people to follow individual journeys in order to understand more about the complexity and challenges of migratory experiences.

This is where O’Donoghue’s work resonates strongly with my own. Her installation is composed of multicoloured paper boats, each of which represents a person who was recorded as drowned in the Mediterranean during 2016. She aims to depict the monthly loss of life by using 12 different colour combinations to marble the paper. This helps her to highlight the ways that changes in the weather, season or policies surrounding migration in Europe can affect the number of people who have died.

O’Donoghue draws on data on the deceased collected by the IOM Missing Migrants Project, yet importantly seeks to emphasise the people behind the statistics. “Every one of the 5,083 paper boats symbolises a loss of someone significant: a daughter, son, neighbour or friend,” she explains. By handwriting titles such as “mother”, “friend”, “baby” on each boat, O’Donoghue seeks to humanise people on the move rather than rendering them inhuman as “numbers” associated with the fear of migration.

Academic Lilie Chouliaraki has argued that humanitarianism today has been reduced to a mere spectatorship of the victimhood of others. By contrast, our installation invites visitors to become more intimate with the details of people who make the risky journey across the Mediterreanean Sea. This involvement refuses the role of passive spectator in the face of the violence of contemporary bordering practices. And we hope it will encourage people to take home stories and ideas of what they can do to make a difference wherever – and whoever – they are.