Amira Merabet, a 34-year-old woman, was burned alive in the Eastern Algerian town of El Khroub in August. Her crime: refusing a man’s advances.

The murder shocked Algeria, and protests were held across the country – in Constantine, Oran, Algiers and Béjaïa – to pay tribute to female victims of violence.

This was not a crime without precedent. In Béjaïa, Merabet’s photo was placed among that of women assassinated by Islamists during the 1990s. They included 17-year-old Katia Bengana, who was killed for refusing to wear the hijab.

The linking of these two murders shows that memories of the civil war that raged from 1992 to 2002 remain vivid in Algeria. And Merabet’s death shows that Algerian women’s struggle for rights is neither over nor forgotten.

Revolutionary women

Female activists have long challenged their marginalisation in male-dominated environments. And Algerian women’s struggles go back to the revolutionary war of 1954-1962.

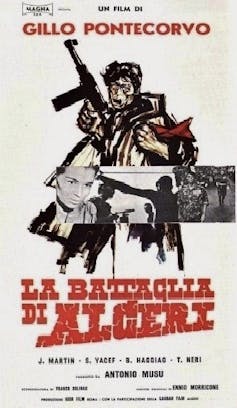

In 1956, Algerian women participated in a series of terror bomb attacks launched by a nationalist guerrilla network. The campaign was later popularised by Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 film The Battle of Algiers.

In 1958, during a nationalist meeting at the Casablanca Labour Exchange, a group of Algerian women spoke before hundreds of men, saying:

You make a revolution, you fight colonialist oppression but you maintain the oppression of women; beware, another revolution will certainly occur after Algeria’s independence: a women’s revolution!

The women had to speak up because the nation’s anti-colonial revolution was so strongly dominated by men. But their words could also be seen as the indirect result of French colonialist propaganda, which claimed to want to “emancipate” Muslim women, but which was also intended to counter Algeria’s nationalist struggle during 1957-1959.

Indeed, the colonial authorities’ campaign of unveiling Muslim women led to the showcasing of “emancipated women” to promote French ideals.

Women intellectuals in Algeria

In 1947, the anti-colonial Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Liberties (MTLD) created the Association of Algerian Muslim Women (AFMA) despite its patriarchal structure.

Run by Mamia Chentouf, the AFMA promoted a type of feminism that was devoted to charitable activities, acknowledged and defended the biological differences between men and women, and affirmed Arab-Muslim culture.

Between 1949 and 1950, the MTLD’s newspaper L’Algérie libre published a lecture by Lebanese feminist Anbara Salam Al Khalidi highlighting women’s participation in Arab civilisation; solidarity messages from Egyptian feminist Doria Shafik; and echoed debates within the Arab-Muslim world about the “role of women”.

The newspaper argued the issue could only be resolved in a cultural framework free of Western influence.

The Algerian revolution that followed, and the violence against women it entailed (arrest, torture, rape and murder) undoubtedly contributed to wider recognition of women’s involvement in the anti-colonial struggle. It demonstrated that a woman such as Nassiba Kebal, a young activist who was arrested and mistreated by colonial authorities, could suffer as much as any other activist.

Still, progressive statements promoting gender equality in a free Algeria faced conservatism from nationalists little accustomed to female activism.

Veils and short skirts

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Algerian women in France were also critical to developing narratives of feminism in the Muslim context.

The French-based Algerian Workers’ Trade Union (USTA) passed a motion during its first convention in 1957 on “Algerian woman’s liberation” and appointed Kheira Moujahadi to represent a delegation of working women on its executive committee.

The union was close to the Algerian National Movement (MNA), and chaired by veteran nationalist leader Messali Hadj

The USTA’s newspaper, La Voix du travailleur algérien, published in 1958 an article by a woman known as Yamina B. which argued for emancipation by giving a voice to Algerian working women. Young female unionists such as Baya Maanane and activist Fatma Mezrag also promoted women rights to male audiences during May 1 Labour Day meetings that same year in Northern France.

The second convention of the USTA passed a motion on Algerian women’s emancipation, after women publicly expressed their discontent with their situation. Some, like A. Hedjila, criticised the French authorities’ unveiling “masquerade” and stressed that women’s emancipation belonged to unionists.

For Messalists, the evolution of women’s status was not “an issue of veil or short skirt”.

But the USTA’s efforts to advance women’s rights were not enough. Unionist Fatma Mezrag said in 1959 in Lille, a working class town in the north of France, that fighting colonialism would not be enough to liberate Algerian women. She said men had to address their selfishness, lust and oppression.

She clearly recognised that French colonialism wasn’t the only obstacle on the path of Algerian women’s liberation.

This singular feminist movement ended with the collapse of Messali Hadj’s movement on the eve of Algerian independence that cool place in 1962.

And despite the progressive views of some male leaders within the country, Algerian women couldn’t directly challenge religious oppression, economic exploitation, or nationalist patriarchy in a newly independent Algeria.

Still, history shows that they could, if only temporarily, shift the conversation in favour of equality, modernity and emancipation, especially among the working class.

The struggle continues

In recent years, there has been a revival in interest in the history of the Algerian women’s movement from colonial to post-colonial eras.

This is largely because women are still having to fight for equality in Africa’s largest country.

Across Algeria, women are protesting against unemployment and campaigning for their rights.

They are doing so not as pioneers, but as members of a women’s movement that goes back generations.