It is that time of year again, when the International Institute for Species Exploration based at the State University of New York announces the Top 10 new species.

This year the announcement has been timed to honour the birthday of Carolus Linnaeus, the founder of modern taxonomy, who was born on 23 May 1707. Linneaus not only established the system we still use to classify species, he and his students made a heroic start by naming 4,400 animal and 7,700 plant species. Linneaus would be astonished to know that modern scientists named 18,000 new species just last year, and that current estimates are that 10 million species still await discovery.

With that context, it should be clear that the Top 10 species of the year are ambassadors for this massive endeavour and were chosen both to highlight the passion of the scientists involved and to activate the imagination of people who do not usually think about taxonomy. The classification of the world’s diversity is critical to understanding our planet and to the preservation of life on earth.

I have found a couple of themes to organise this year’s Top 10. I’ll call them eggs and branches – what species do with their eggs is key to their identity and behaviour, and the evolutionary branches they sit on is no mere metaphor, as some of them live and grow on or look exactly like actual branches.

So let’s start with the egg theme, and the new dinosaur that is an Oviraptorosaur (or “egg thief” lizard). Originally thought to be egg-eaters, it is now believed that fossils found among nests and broken egg-shells belong to feathered dinosaurs who were protecting their young. These early dinosaurs were part of the transition to birds but are not exactly birdlike: about the size of a small car, and found in a geologic region known as the Hell Creek Formation, the scientists who named Anzu wyliei have dubbed it the “chicken from Hell”.

Speaking of hellish things to do with your eggs, the next species is a wasp that uses corpses to feed and protect her eggs. That’s right, the eggs of Deuteragenia ossarium are laid inside paralysed spiders packed into a hollow stem, with the creative twist of packing the end of the stem with a pile of dead ants. The ants produce a chemical signature that confuses parasites that want to harm their young brood. The species name “ossarium”, or a place for the bones of the dead, comes from this unique behaviour.

The white-spotted pufferfish is so obsessed with protecting their eggs that they build intricate circles in the sand that are so large (2 metres) and so beautiful that scientists spent 20 years wondering what they were for. The discovery of the culprit led to the identification of this new species of fish, which has been filmed doing its thing in the seafloor near Japan. The ridges and grooves built by the male pufferfish protect the eggs from turbulence.

A new species of fanged frog found in Indonesia has made the Top 10 due to a conspicuous lack of eggs. Most frogs release eggs and sperm into the water where fertilisation occurs outside the body. Only a handful of frogs break this rule and fertilise their eggs internally, but these either produce eggs ready to grow or tiny froglets. Limnonectes larvaepartus, the new frog found in Indonesia, is the only frog known that gives birth to tadpoles.

I’m going to stretch my egg theme for the next species by explaining that it provided the germ of an idea. The Moroccan flic-flac spider was actually discovered by a bionics expert, for whom the species is named. Cebrennus rechenbergi is a type of huntsman spider that lives in the Moroccan desert. It hides in silk-lined burrows during the day and is active at night. However, its claim to fame is a unique mode of locomotion whereby it cartwheels like a gymnast when disturbed and the movement is so unique and efficient, Prof. Dr. Rechenberg used it as the inspiration for a new robot called a Tabbot. You can view films of both the spider and robot here.

So that’s it for the egg theme, and time to think about branches.

A new plant (Balanophora coralliformis) found in the Phillipines is a root parasite, which means it draws its nutrition from other plants and is incapable of photosynthesis. This means it does not have chlorophyll, so it isn’t green, and has branching tubers that make it look like a brown coral living in the forest.

I love the way that life surprises us – the Top 10 list includes both a plant that does not bother with photosynthesis and an animal that does. Solar-powered sea slugs harvest algae from coral and sequester them in their gut in order to supplement their diet with nutrients from sunlight. The Japanese sea slug Phyllodesmium acanthorhinum has both a branched gut to hold these miniature solar cells and a branched body shape. With vivid colours and graceful movements, they are so beautiful they were recently named the Opisthobranch of the Week.

I just love stick insects, so the inclusion of a stick insect in the Top 10 has my full approval. Phryganistria tamdaoensis was found in the Tam Dao National Park in Vietnam and belongs to a group known as “giant sticks”. Let’s face it, some of these creatures are so big they look more like branches. The Tam Dao Giant Stick was cultivated in captivity for years before being named and has already been filmed by another stick insect lover.

High in the branches of the cloud forests of Mexico, a colourful plant known as a bromeliad grows on trees and rocky cliffs. Growing up to 1.5 m tall, Tillandsia religiosa was used to decorate Christmas scenes by villagers long before science gave it a name.

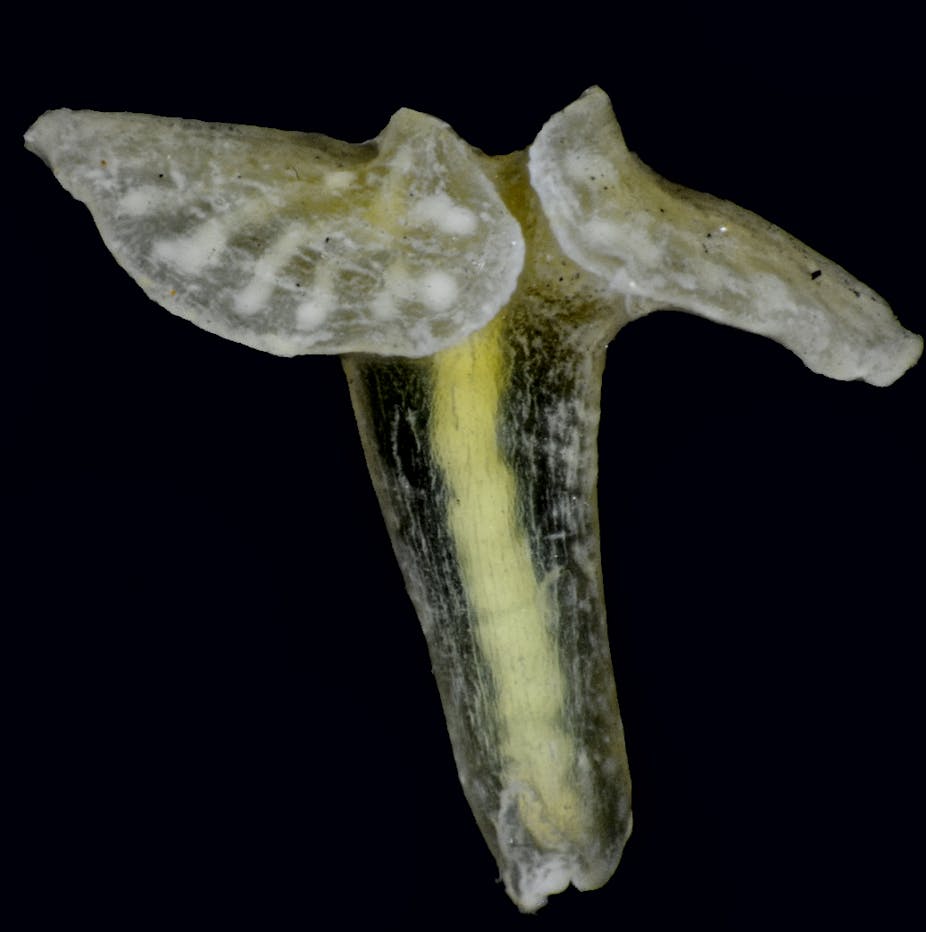

Last but not least is a species whose very name (Dendrogramma enigmatica) refers to the branching diagrams we use to draw evolutionary trees (see its picture at the top of this post). Found in Australia in my own state of Victoria, this species has several claims to fame. It may represent an entirely new phylum, which means a major new branch on the tree of life.

Discovered in 1986, the species took so long to name precisely because its existence led to further questions about the origins of multicellular organisms. When we say that its closest relative might be either a Ctenophore or a Cnidarian we are entering the realm of deep time and issues surrounding the evolution of the first animals, a topic I’ve explained before. With similarities to Precambrian faunal groups, the placement of this new species may result in the movement of extinct kingdoms. Their taxonomic description as “incertae sedis” literally gave me chills: the Latin phrase indicates that nobody on earth knows where this species belongs, yet.

Dendrogramma enigmatica is one of two species found on the deep ocean floor, at up to 1000 metres below the surface. With a single mouth opening and no gonads, they look like mushrooms, although they are definitely animals. If we had access to DNA many questions about their origins could be answered, but these specimens were preserved in a way that kept their cell structures intact but destroyed the DNA.

The branches of the tree of life look just like the branches in the lobes of D. enigmatica. As an enigma this species illustrates both the challenges we face in the classification of life, and the connections we see among all living things when we look more closely.