Most people only really hear about what happens outside abortion clinics when extreme tactics are used. But our research has shown it is the presence rather than the conduct of anti-abortion activists that often distresses women.

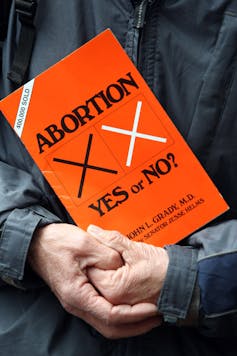

There are a number of different organisations and groups that operate outside clinics. Many have links to US organisations. Most aim to approach women as they are entering and leaving clinics. They offer them leaflets which claim that abortion is a significant risk to women’s health. Some use large posters of graphic images of aborted foetuses. Others pray.

We spent 18 months researching people accessing abortion services as well as observing and interviewing the anti-abortion activists who stand outside clinics or participate in marches. It’s clear that the two sides in this debate fundamentally disagree about what it means to harass someone outside a clinic.

Helping or harassing?

Anti-abortion activists describe their activities as “educational”, “prayerful witnessing” and “pavement-counselling”. Those that organise around prayer in particular strongly deny that they are protesting.

All of the groups argue that they are offering information and a service that women would not receive otherwise. This assumption is based on a belief that abortion clinics in particular, and wider society in general, cover up the “reality” of abortion. Many see providers such as the British Pregnancy Advisory Service as essentially an industry which promotes abortion to make money. On a recent local radio debate, a spokesman from Abort 67 stated that abortion providers “are making money from hiding information from women who deserve to know all the facts”

Not everyone involved in the anti-abortion groups outside clinics is religious but it is clear that the majority are religiously motivated. Their religious understanding of the sanctity of life shapes their understanding of abortion practice and means that they strongly believe the consequences for women will always be harmful. They suggest that women do not know the “reality” of abortion – that a developing foetus will be terminated. This seems to be based on the belief that motherhood is both central and sacred so women would only reject motherhood due to fear or coercion. Their focus is as much about saving women as it is on saving the foetus.

When women change their minds about abortion, it is used as proof that their mission is both purposeful and successful. The activists believe this would not have happened without their intervention. At the 2016 March for Life, a woman who had changed her mind was seen as the star attraction and counts of the numbers of “saves” are proudly noted on websites and in newsletters.

The women encountering activists see the experience very differently. Many report feeling angry, stressed and distressed by anti-abortion activists. Although women reported more extreme incidents such as being filmed or followed, our research shows that many were upset by what might be seen as more mundane encounters, such as being watched or prayed for. Most women accessing clinics did not want to discuss their decision with strangers and found being approached intimidating and intrusive. Even when approached without aggression, women often consider this to be harassment. And even if anti-abortion participants might believe that their prayers could bring comfort, some women find being prayed for highly offensive.

In order to explain why so many women are distressed by the encounters, we need to consider the broader context of street harassment. Women are subjected to many unwanted intrusions into their daily lives. Being watched or approached by strangers when they do not necessarily know what their intentions are is likely to make some women fearful.

Although most of the anti-abortion activists may not deliberately intend to harass women, their actions on the street are at best an unwelcome presence. At worst it is highly intimidating. It also draws unwanted attention to what women see as a private medical decision. It can feel like a “paparazzi encounter”. Their private business is made the object of public attention.

The meaning of harassment

At the heart of this debate is a dispute over what actions constitute harassment. The anti-abortion activists may have good intentions but our research suggests that the majority of the women they approach do not want their intervention and many are intimidated by their actions.

Anti-abortion activism outside clinics is not a new phenomenon but there has been a shift in the strategies used. British activists have prayed outside clinics before, but the targeting of specific clinics, especially by people who are paid to be there, the focus on pavement counselling and the use of graphic images are the kind of tactics seen in the US, where the anti-abortion movement is more aggressive and has included vandalism, arson and shootings.

Yet while there is evidence that the anti-abortion movement is becoming more mobilised and adopting new tactics, there is little evidence to date that it is growing significantly or having a wider impact on public opinion in the UK. In the main, only a minority of very religious people feel that abortion should be banned in all cases.

Our research has shown that there is often public attention on the most aggressive tactics such as being filmed or followed but “prayer vigils” are also widely experienced as intrusive and distressing. This is so even where anti-abortion campaigners conduct themselves in ways that are pleasant and respectful.

Many women reported that the very presence of these activists outside clinics directly challenged their own right to medical confidentiality. But the strong belief among anti-abortion activists that they are saving women from themselves as well as from a diabolic industry means that they are unlikely to ever see what they do as problematic to the majority of women.