Arab-Islamic education in general and Koranic schools in particular are largely excluded from programs advocating for education for all in Africa. Yet this education concerns a large number of children, many of whom are considered as “out-of-school” by the public authorities. Consequently, recognising its existence, importance and diversity is a prerequisite for building a dialogue framework between all stakeholders. The starting point is to go beyond certain clichés.

Cliché 1: Arab-Islamic education is recent phenomenon in Sub-Saharan Africa

Arab-Islamic education appeared in Sub-Saharan Africa at the same time as the dissemination of Islam in the 11th century. It was initiated by Arab-Berber merchants in West Africa and was subsequently spread by religious brotherhoods in the 19th century.

To compete with Koranic schools and attract Muslim students, the colonial administrations subsequently created formal madrasas to train competent Arabic-speaking civil servants. From the 1940s, an Arab-Islamic education market gradually emerged, with entrepreneurs supported by external funding from the Maghreb and Middle East. Since 2000, in seeking to integrate them into the formal education system, some states have gradually developed new educational institutions (integrated or modernised Koranic school, Franco-Arab schools) to incorporate them in the formal education systems.

Cliché 2: Arab-Islamic education is only memorising the Koran

Arab-Islamic education encompasses a great diversity of institutions that, although they vary depending on geographical contexts, are present in nearly all African countries. Due to the lack of data, this category of educational institutions is still scarcely taken into account by researchers working on education in Africa and education system planners.

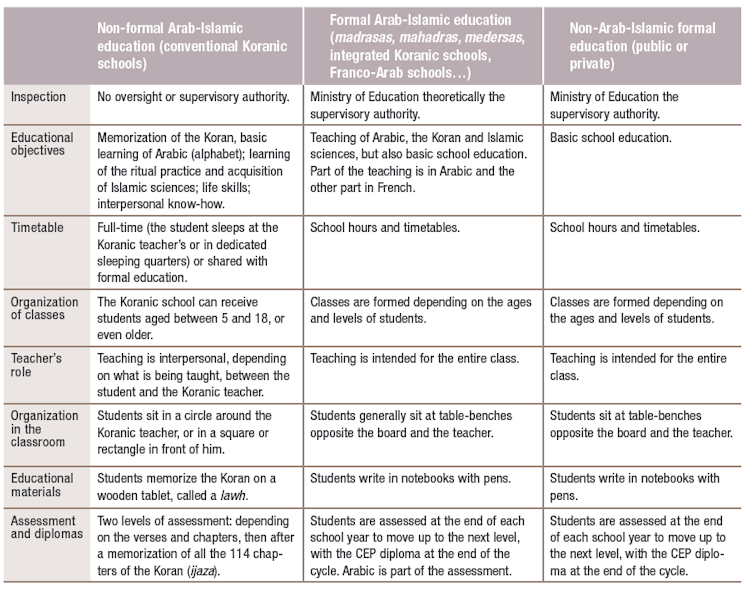

It is possible to differentiate Arab-Islamic education between institutions depending on their level of formalisation and recognition by governments. Formal education is the education that teaches the national curriculum within an official framework recognised by the country’s institutions. It is managed by the national education system in line with official teaching methods, operating rules, validation processes and calendars. Conversely, non-formal education is outside the official framework. It does not train in the competencies expected in the national curriculum.

Differences between Arab-Islamic educational institutions for children of primary school age.

Cliché 3: Arab-Islamic education is a negligible phenomenon in Sub-Saharan Africa

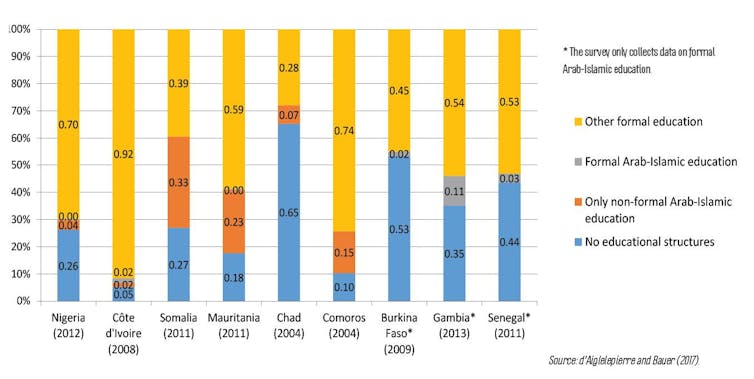

Quantifying the number of children attending Arab-Islamic education institutions is a challenge, as the vast majority of African countries do not collect such information. The data collected by the information systems of the various ministries of education focus on educational institutions considered to be formal. Information about conventional Koranic schools is therefore not generally collected.

In some countries, household surveys give an idea of the percentage of children of primary-school age who only attend Koranic schools: it is low in Côte d’Ivoire (1.5%) and Nigeria (3.5%), but higher in Chad (6.8%), the Comoros (15.4%), Mauritania (23.1%) and Somalia (33.5%). A low proportion of children are in formal Arab-Islamic education, with 0.4% in Mauritania, 0.46% in Nigeria, 1.7% in Côte d’Ivoire, 1.8% in Burkina Faso, 3.4% in Senegal (Franco-Arab schools), but some 10.9% in Gambia. Students in non-formal Arab-Islamic education consequently account for more than half the children considered to be “out-of-school” in countries such as Mauritania, the Comoros and Somalia.

Percentage of children of primary school age by educational status.

Cliché 4: Arab-Islamic education is for boys and for the poor

A large proportion of Muslim households combine public or private formal education with a conventional Koranic school. However, a significant proportion of households settle for a conventional Koranic school that is not exclusively for boys and the poorest households. A large number of girls are accepted in them. In countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, Somalia and Senegal, non-formal Arab-Islamic institutions can sometimes be even more favourable for girls than formal school.

Conventional Koranic schools concern an intermediate category between the most urban and richest households, whose children are in a formal educational institution, and the most rural and poorest households, whose children are not in any educational institution. By contrast, formal Arab-Islamic education concerns more boys and households with a level of income equal to or higher than those who choose public or private schools.

Building a compromise between African governments and Arab-Islamic education

In most African countries with a significant Muslim population, there is a dual education system: one formal Western-based, and the other non-formal and religious. Initiatives are being carried out either by religious movements, initially reformist then brotherhoods, or by governments, sometimes supported by international and non-governmental organisations, to flesh out a “third way”, which would reconcile demand for religious education and the need to align with international education standards.

Reform initiatives have been launched: project to support bilingual education (French-Arabic, English-Arabic), program to support “modernisation” (Senegal), “renovation” (Niger) or the integration (Mali) of Koranic schools into national primary education cycles. In Senegal, since 2002, the government has set out to “modernise” the daara (Koranic schools) via the Daara Inspectorate and the Arabic Education Division, and build new Franco-Arab schools nationwide. Certain governments are moving towards a “hybrid” system, where religious and Arab-islamic education are combined with “secular” education where some basic education is given in French or English for reading, writing and mathematics. These models are, however, still in the experimentation phase. School curricula are not fixed and the number of hours spent in class varies depending on the schools. Furthermore, the recruitment and training of teachers in Arabic and religious science are not fully effective and the number of inspectors in the Arabic language remains very low. In addition, the future insertion of students when they leave these schools has so far not been a priority for the reflection of public authorities.

Today, there is a need to define a framework in which a compromise would be established between the various current movements which Arab-Islamic education institutions, on the one hand, and governments, which are responsible for organising their education system, on the other hand. Efforts need to be made by all the stakeholders in order to overcome the mutual incomprehension, build a common project, and innovate to improve education in Sub-Saharan Africa in terms of access, equity and quality.