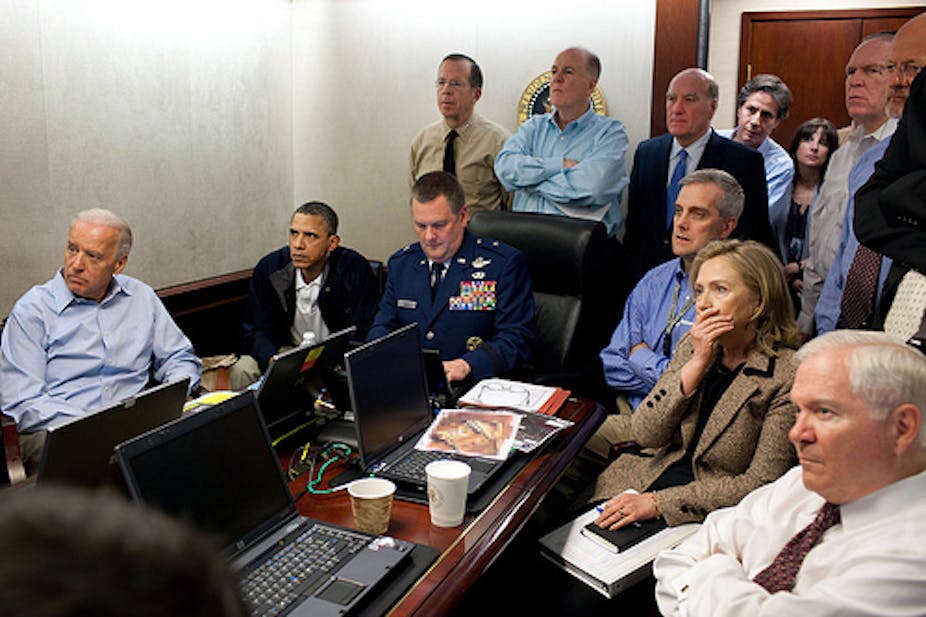

Superficially the death of Osama bin Laden on May 1 in Pakistan is a spectacular event; the sort that might one day elicit the “Where were you” type question from a curious youth hearing about al-Qa’eda for the first time at school.

But in concrete, practical, and immediate terms, it is much less important than might appear, including in its impacts in and on the Arab world. There are several reasons for this.

The first issue to recall is that there are greatly varied levels of support for bin Laden’s views and for al-Qa’eda across the Arab countries and within individual countries.

But such support is not high these days, and has fluctuated in 2001 and mostly declined in more recent years.

Pew research in 2010 showed “confidence” in bin Laden among Muslims of 19% in Egypt (down from 27% in 2006), 14% in Jordan (versus a high of 61% in 2005), and only 3% in Lebanon, (against 19% in 2003). In other words: support or respect for bin Laden in the Arab world is modest, varies enormously and has been trending downwards for several years. Even in Pakistan, where he enjoys a true base of support, bin Laden’s popularity has plummeted in the last few years.

Second, and also important, is why bin Laden appeals to some people. Only a small number of Muslims really want to live under an Islamic state as envisioned by bin Laden and his ilk: perhaps 5% of the Muslim world by most polling and estimates – if even that – support him first and foremost because of his political ideology or his theological views.

Rather, he has a wider but more lukewarm popularity for two reasons. Above all, he publicly and bluntly criticises the United States and its policies in the region. Many people in the Arab world, even where they respect American technology, education, or political values, resent its support for Israel, its military interventions in the region, or its past or present support for authoritarian local leaders.

Also important as another factor is that most leaders in the region do not speak out the way bin Laden does; the majority, in fact, are seen by their populations as brutal and illegitimate at home, and yet too cowardly or too seduced by the US to dare speak out against it – a reason for the protests that have been seen across the region this year.

The third point is related to this leadership dynamic: what people in the Arab world are looking for is strong, courageous leadership rather than a particular ideological direction.

Where the 2011 protests in the region have removed leaders, al-Qa’eda’s support is actually undermined or at least threatened. Secular “people power” has removed two leaders, and will probably claim at least a couple more; something al-Qa’eda has promised but never delivered.

Even where old leaders remain, many are on notice. If this makes them speak out more sharply, or reflect popular opinion more accurately, it may well be at the expense of al-Qa’eda types. Had bin Laden been killed a year or two ago – when autocrats like Mubarak and ben Ali were still in power, and others were more confident than today – this might have been very different.

Fourth, there are many al-Qa’eda groups, and even more that are like-minded in their politics. There is “al-Qa’eda in Iraq”, much weakened these days by improved US tactics in that country.

There is “al-Qa’eda in the Arabian Peninsula”, a mostly Yemeni group of al-Qa’eda members and affiliates; a real threat but more focussed on opposing the Saudi Arabian regime and the US military role in the region than on striking the US mainland. There was “al-Qa’eda in the Maghreb”, which emerged from a particular, mostly-Algerian base, but it merged with the main al-Qa’eda organisation, now very decentralised anyway, in 2006.

And there are many other groups which are like-minded to al-Qa’eda, but separate. Thus, while losing bin Laden is potentially a psychological blow, except for a core al-Qa’eda executive in Pakistan they are not losing an active, operational leader.

Occasionally terrorist groups simply fall apart without a leader – Baader-Meinhof is one example – but this will not be the case with al-Qa’eda. Some of its variants might lose a handful of supporters, but there is equal risk that bin Laden’s death will simply confer a martyrdom on him among those predisposed to his politics or leadership anyway.

Nor, however, will it gain al-Qa’eda-type groups many new followers: a large majority in the region, even if they might momentarily nod at bin Laden’s anti-Americanism, have no taste for the society that al-Qa’eda would create.

Ultimately, as with its impact more widely, of bin Laden’s death is a symbolic victory for the US. While surely a matter of satisfaction for many, killing bin Laden carries little strategic or tactical importance given his peripheral role in what remains of the al-Qa’eda organisation.

Bin Laden’s support and al-Qa’eda’s cohesion were already falling, and their ability to dictate the terms of the fight with the West was mostly gone.

While al-Qa’eda remains a threat in many ways, and they may now follow with revenge attacks against the West as a reminder of this, Osama bin Laden ceased being the main source of this threat long before his death.

More stories about this topic