Gold poses a classic conundrum: it’s both a blessing and a curse for communities that discover they’re sitting atop this coveted resource. And for many people in rural Niger, which has been plagued by food shortages and poverty, it is now a key part of their survival strategy.

Nearly 64% of the country’s poorest inhabitants – those whose annual per capita consumption is lower than the poverty line of €278.42 per person – live in rural regions. Local mixed farming is heavily dependent on weather conditions, making it an unreliable source of income and sustenance.

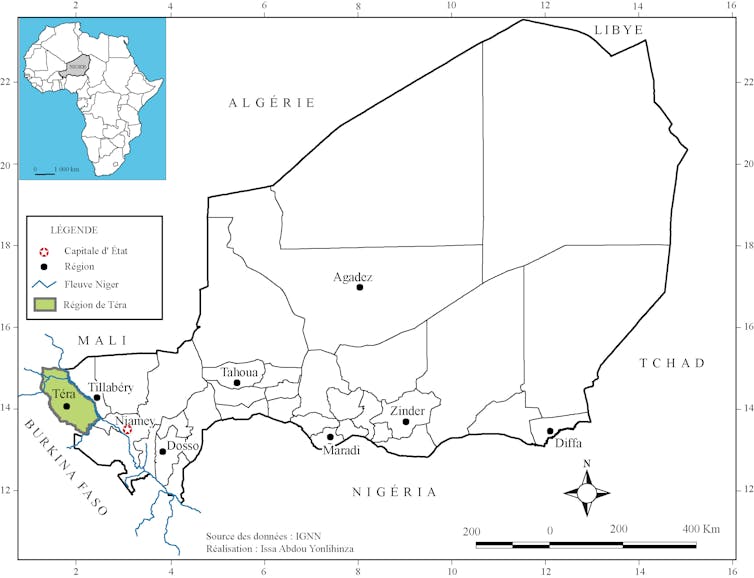

Increasingly, residents are flocking by the tens of thousands to the mineral-rich Liptako region in the southwestern part of Niger (on the Sahel stretch) to seek their fortunes.

Though several West African countries have seen placer goldmining – the practice of panning alluvial deposits of sand and gravel – on Birimian sedimentary rock formations for some time, Niger’s mining industry has long been centred on uranium extraction. But since early 2000s, it has begun branching out into gold and other lucrative subterranean resources.

Mining can mitigate agricultural shortfalls and contribute to the local area economy, but, as history elsewhere in Africa shows it also has unpredictable and irreversible social, migratory and environmental consequences.

The gold mines of Sahel

The Liptako region, which encompasses not just Niger but also parts of Burkina Faso, Benin and Mali, is rich in bedrock formations. Since the 1970s, there’s been convincing evidence that some communities there are sitting on considerable mineral wealth.

The region saw its first big boom in the mid-1980s, after famine following a bad harvest in Niger in 1983 spurred large-scale migration to the capital, Niamey, and to coastal countries like Ghana, Togo and Côte d’Ivoire. Seeking to stem the rural exodus, the government called on local authorities, both traditional leaders and public officials, to ramp up the placer mining already practised in the region.

Since then, the population in Téra, a department in southwest Niger 160 km from Niamey, has doubled every 15 years, and 61% of people are under 20.

For Téra’s young and growing population, employment has become a key issue. The mining industry is dominated by international big business and for much of the region’s uneducated, inexperienced population (mostly men), it is hard to break into.

As a result, placer mining has become more attractive to them. The spectre of unemployment, combined with the rise in international gold prices in 2016, has also encouraged locals to strike out on their own, launching small-scale gold mining endeavours that cover several sites over increasingly long distances. Many Téra residents have migrated to boom towns within the department.

Gold: a fast and growing attraction

Komabangu village is a good illustration. It sits close to the largest placer mining site in the region. Komabangu’s population has skyrocketed, jumping from just 200 inhabitants in 1999, when mining started, to 25,000 in 2004.

According to my research, Komabangu has also become a major draw; today’s residents of this urbanising centre hail from rural communes in all three districts of Téra, representing almost 65% of total population. I found a high level of diversity: 8% of people come from Goruol commune, 19% from Kokorou commune, 57% from Dargol commune and 9% from Diaguru commune.

Komabangu’s fame has reached well beyond Téra’s borders. Among those I surveyed, 18% were Nigeriens from other areas. I also spoke with migrants from neighbouring West African nations, including Burkina Faso, Mali, Togo, Nigeria and Benin.

More money, more problems

Placer mining has greatly altered life in the Téra region, leading to inter-ethnic social and cultural exchange and radical structural changes.

Monetised trade has gradually replaced traditional bartering, resulting in increasing personal revenue for a population that, prior to the discovery of gold, was largely comprised of farmers.

Consumption patterns have altered too. New products such as mobile phones, ice cream, soft drinks and Western-style clothing have come available in Téra, and locals now have currency to buy them. This has opened up new markets for retailers coming from Niger’s cities, who are now setting up shop near mining sites in Téra.

Monetisation has likewise transformed some aspects of social and cultural life. In wedding ceremonies, for example, gifts have been replaced by money.

But, as it is wont to do, mining has also created conflict, awakening latent rivalries between communities and creating new tensions. As soon as gold is discovered in a given area, land ownership disputes tend to arise.

The villages and ethnic communities of Sonray and Gurmantche, are fighting for control over a site called Chaka, located at the border of both villages. In Komabangu, too, tensions have been high, as the chieftaincies of two districts, Dargol and Kokoru, fight over lucrative sites.

Gold’s environmental impacts

Mining is also taking its toll on the local landscape. To increase gold production, several environmentally damaging chemical products, including cyanide, acids, detergents, and explosives, are used by most miners, especially small-scale ones. Their use contaminates soil and destroys ground cover.

Amalgamation, a technique for extracting gold from ore using mercury, is particularly damaging. In the distillation phase, generally carried out in the open air at placer mining sites, a significant portion of the chemical enters the environment as a polluting vapour.

Gold mining also means increased consumption of water, which is pumped out in high volumes to wash the ore and for miners to drink. This can have a profound impact on the local water table.

Forests surrounding mining sites in Téra have also seen excessive tree felling as hundreds, if not thousands, of placer miners seek to work and live at the same place. This deforestation has endangered the shelter, food sources and reproductive habitat for several species, and led to the immediate disappearance of mice, rats, lizards and snakes. Insects and earthworms are also suffering.

Designing a more stable future

It is unclear how long Téra can sustain such booming growth and massive exploitation of its natural resources.

To date, Niger’s government has taken few measures to address rural poverty, the cause of this mass migration, or to mitigate the human and environmental impacts of the unplanned demographic shifts that are altering life in the region.

Already European and North African countries are struggling to deal with the flows of thousands of sub-saharan African migrants who have fled home over the past decade. Failing the implementation of a real policy for balanced rural development, there is a very real risk that Nigeriens from Téra and surrounding regions will join the exodus.

Translated from the French by Alice Heathwood for Fast for Word.