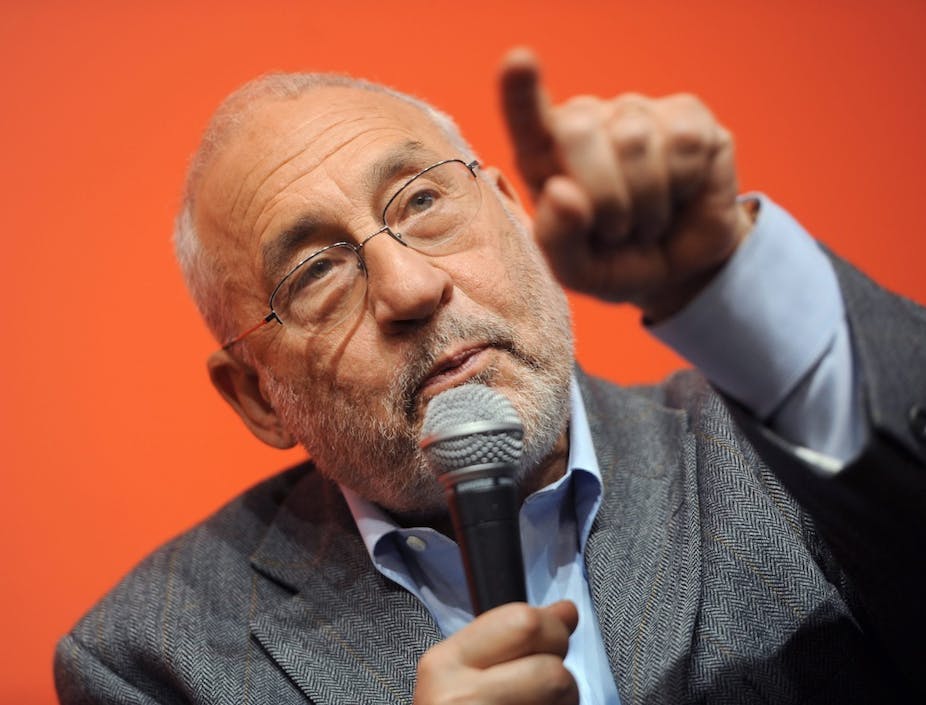

Nobel Laureate and renowned economist Professor Joseph Stiglitz has been packing out lecture theatres in Australia in the past week. During his whirlwind tour, he’s talked about why inequality matters in society, the dangers of Australia moving towards expensive US-style education and warned about this country emulating America’s health care system.

He spoke to The Conversation about the things Australia should do – and should avoid - as its economy transitions from its mining boom, whether some inequality is good for society, the popular furore surrounding French economist Thomas Piketty, the rise in Australia of the corporate “rent-seeker” phenomenon, and how economists can be more ethical.

Transcript

Helen Westerman: Australia’s economy is at a critical phase right now. It’s moving from the investment phase of our resources boom, but other sectors appear relatively slow to take up the slack. We’ve been told we should become a services economy. I asked Professor Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel Laureate and renowned economist, what things we need to do, and what things we should avoid doing right now.

Joseph Stiglitz: I think that framework is precisely right. Manufacturing employment is going down globally, and the ability of advanced countries to.. they will be losing shares of that to the emerging markets who have more competitive labour markets, and lower wages. For Australia to position itself as a service sector economy for education, research, healthcare, and tourism, for Asia and particularly for China, it makes sense. I think the success of doing that is going to make sure that you have a vibrant education and healthcare research sector, for your own people.

If you have a healthcare system that is able to deliver for Australians to have good healthcare efficiently, it will make it competitive in the global healthcare market, and same thing if you a high quality education system, you’re going to succeed. And this is where it is important to realise the success of the United States has been based on exporting educational services has been based on the quality of the education system. We have been lucky to get a lot of philanthropy to support our higher education. I think other countries have not succeeded. In the absence of that, it has to be the government that provides that support.

Helen Westerman: So the things that we need to do are boost education and ensure that we have got a healthy population. What are the things that we need to avoid doing?

Joseph Stiglitz: I think you need to avoid letting an uncontrolled, for-profits sector grow. In the United States, the for-profit schools are good at two things: one, exploiting poor people, and two, using their lobbying power to make sure the government doesn’t regulate them, to stop them exploiting poor people. In doing that, they’re harming the reputation of America’s education system. Anybody that didn’t know about this, that came to the United States, would have a terrible experience. Australia is going to have a brand name for education and healthcare, and you have to maintain that. Part of that brand name is quality, and that means to make sure you have quality, you will need strong regulation.

Helen Westerman: We are at a period where our most recent budget is looking to make cuts to those sectors, and to introduce a more American style model. You’ve been quite critical of that approach.

Joseph Stiglitz: That’s right. We have many things to imitate in the United States, but those are two things that I would certainly warn against. Our healthcare system provides much fewer outcomes, at twice the cost. Why would anyone want to try to imitate a system that is such a failure. It’s a particular failure obviously for ordinary American citizens, but even on average its a failure. Even the average statistics are dismal compared to those of Australia, and the costs are enormous.

I think it is widely recognised to be the most inefficient healthcare system in the world, and why you would use that as a model is beyond me. In education, it is true that US schools are, I think, among the best in the world. But what I would emphasise is that it is not because we have a market-based competitive model. We compete, but we compete for government grants and we compete on quality, but there is no price competition. We compete to help poor students, we compete to have diversity, but these are not things that are part of a normal market economy.

That’s because we’ve been successful in getting a lot of philanthropy to support our “Harvard’s” and our “Columbia’s.” I think it would be a good thing for you to compete for philanthropists to give the same type of support that we have. But that’s very different from what the government is talking about. If you look at the average performance of our education system, it is really nothing to write home about, it is not something that others should imitate. Our college graduation rates, our performance in international standardised tests are really not very good.

Helen Westerman: You talk a fair bit about rent-seeking in those sorts of sectors. Do you see Australia heading in that direction?

Joseph Stiglitz: I think it could head in that direction if you follow the kinds of reforms that are being discussed. If you ask the question, why is it that America’s healthcare system is so costly, it’s because there is so much rent-seeking going on between the drug companies, and the health insurance companies. That, I think, is a real risk. It is important to realise the big difference between a market economy, and what I sometimes describe as an “air-socks” market economy, its a phoney economy.

Because, in the end, its the drug companies, who generate so much of their profits, have succeeded in lobbying to get a provision that said the government cannot negotiate prices with the drug companies — that is not a market economy. The for-profit private schools, only survive because of the government-provided loans. The government doesn’t want to provide the loans to these schools, because these schools don’t deliver any education, and they don’t deliver jobs to these students.

But the for-profit schools have lobbied to make sure that we don’t provide regulations that ensure the quality of the education, and make sure that they don’t exploit poor children.

Helen Westerman: At a session with young economists in Hobart last week you discussed the ethics of economics. The Global Financial Crisis showed economic models can do great harm, so how can economists be more ethical?

Joseph Stiglitz: That’s a hard question, partly because I think that it is inevitable that one sees things through particular lenses, and the economics profession as a whole has a tendency to see things through lenses that focus on efficiency, and have more or less turned a blind eye to rent-seeking activities, and tried to underweight the importance of these. The good news is that that is changing, and there a lot more economists who have reflected the kinds of views that I have talked about.

I’ve talked about this Institute of New Economic Thinking. There are a lot more economists who have become more sensitive to the failures of the economics profession in the Global Financial Crisis. As I said at the conference, economists need to realise that the unemployed are not just a number, they’re people. And they’re trying to translate what they’re saying into the impact on individuals.

Secondly, they are trying to break out from their closed circles, because any closed circle starts to reinforce their views. So Chicago economists talk to other Chicago economists, and they come to the view that markets are always efficient. Until you see this enormous crisis that is clearly not consistent with that, and they’re able to still reject that view by saying these problems only happen every 75 or 80 years.

So it seems to me that it is really important that they interact with people other than their small circles of people who see the world through their particular eyes.

Helen Westerman: It could be the case that some people benefit and some people don’t. It comes back to this argument about equality and how much is actually good for a society, and whether equality is even a desirable, or is it an undesirable thing? Where exactly do you fall there?

Joseph Stiglitz: I think the excessive focus on efficiency, with almost no attention to a focus on how individuals and particular groups like poor people are affected, is actually crucial. For a long time economists really shunned talking about the distributive impacts of their policy. I think they are now beginning to do that more.

Helen Westerman: What is your opinion on the work of Thomas Piketty, and some of the amazing popularity that has followed him? Is that surprising?

Joseph Stiglitz: I think he is absolutely right to emphasise the increase in inequality that has occurred. I think he is absolutely right in his key idea that the period from World War II to 1980 was unusual in the history of capitalism, capitalism has typically been associated with high levels of inequality.

What I differ with is I don’t think it is the inexorable result of economic laws, of economic forces. It is a result of policies and politics, it is the result of rent-seeking behaviour, which the laws and regulations help create or don’t do enough to counter. There is almost a tone in his book that this is just the way of capitalism, and my view is that the kind of inequality that we’ve seen is really a result of the fact that we don’t have a well-functioning market economy.

Helen Westerman: The Bank of International Settlements last week called for global central banks to start raising rates. What do you make of that?

Joseph Stiglitz: I think the global economy is not yet in a solid recovery. What we really need is more fiscal stimulation right now. Monetary policy doesn’t have that much effect. It is clearly not the case that we are in a position of a secure and robust recovery.

Helen Westerman: What would you expect the US Federal Reserve to do in terms of their quantitative easing program?

Joseph Stiglitz: They are in the period of phasing down that. The real question is when will they start raising short term interest rates, and they’ve indicated that it is too soon yet. It’s not clear when they will, but they made it very clear that it is too soon.

Transcript has been added since first published