AUSTRALIA IN ASIA: In the second of our series Nick Bisley of La Trobe University examines the responsibilities Australia must take on to ensure security in Asia.

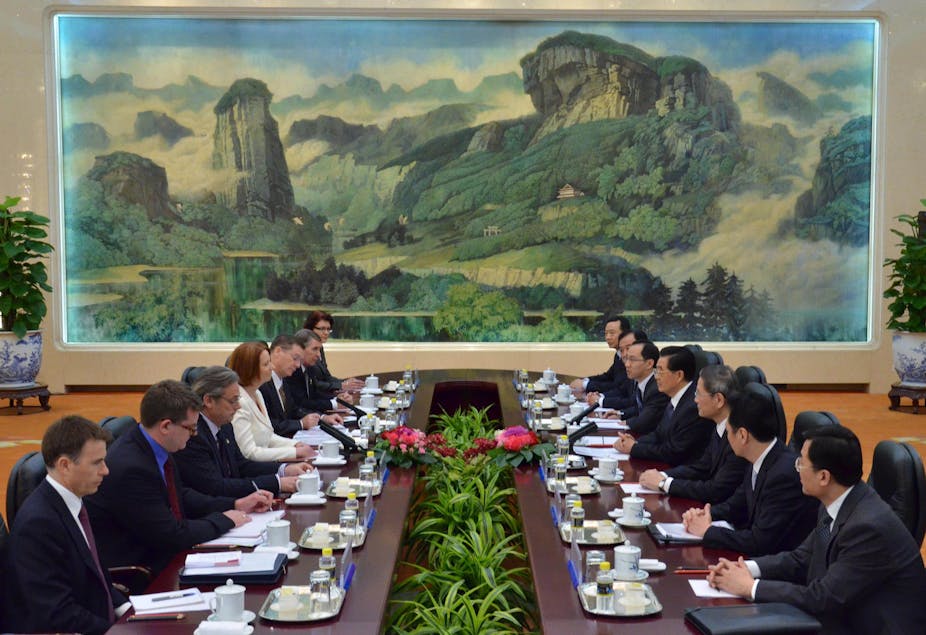

Asia’s economic powerhouses are booming, and Australia wants a piece of action. By embedding the country firmly at the heart of the “Asian Century”, Julia Gillard needs to recognise that with financial benefit comes responsibility to ensure security in the region.

Security Risks, Old and New

From narcotics smuggling in West Asia, to simmering great power rivalry between China and the United States, Asia’s states and peoples must navigate a striking diversity of security threats.

Conflicts over territory are perhaps the oldest and, in Asia, probably the most acute kind of security challenge.

The disputes over the status of Taiwan, the still official state of war that exists between the two Koreas, the unresolved border between China and India and the India-Pakistan conflict over Kashmir are the longest standing.

But there are also battles over resources and strategic advantages in islands in Northeast Asia and the South China Sea.

More military spending

As Asian states have become wealthier they have begun to invest more in their armed forces. Almost all of them are spending heavily on offensive military hardware such as ballistic missile systems, supersonic jet fighters and attack submarines, ramping up tension.

It also fuels a sense of uncertainty and broader insecurity. And Australia is key player in this process. In the 2009 Defence White Paper the government committed itself to long-term real increases in military spending and buying offensive weapons.

Yet another risk to security is the rivalry that results from economic prosperity meeting a powerful sense of ambition.

Asia’s emerging powers are not only large, but they aim to be powers of the first rank and wish to be beholden to no-one.

The competition is on - particularly given that for at least the past 30 years, America with its powerful military, has shown that it intends to maintain its position of pre-eminence.

Transnational threats

If these concerns were not enough, Asia’s societies and peoples are also faced with a series of threats and risks that are crucial to the region’s prosperity.

Transnational terrorism, environmental degradation, unregulated population movement, low intensity internal conflict, infectious diseases, and resource scarcity are the greatest worries.

The region is also prone to natural disasters, the effect of which can be tremendous due to the size and density of Asia’s populations.

No single country can tackle these problems - co-operation is essential.

Regional co-operation

As globalisation as increased uncertainty, Asian states have significantly increased their efforts to co-operate on security matters over the past fifteen years.

They have established an often bewildering array of regional institutions and processes, including the creation of no fewer than 12 multilateral institutions which foster co-operation on security.

From the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), to the East Asia Summit, the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) Regional Forum and the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM+), there is no shortage of talking shops.

And that’s before we take into consideration the “track two” meetings between academics, journalists and policy-makers. There have been 250 of those each year since 2007.

It is true that aspects of security co-operation have made important contributions.

Without this array of institutions the international consequences of China’s rise would have been much more disruptive than has been the case to date.

But this return is fairly meagre given how much talking is done between states.

Talk, not much action

Although Asian states tend to talk up their commitment to security co-operation, the reality is that their willingness doesn’t match their rhetoric.

Why? Partly because there are too many institutional ways to co-operate, which are poorly designed and overlap.

Often they have a very similar membership and a virtually identical work program. Counter-terrorism is talked about in all 12 intergovernmental bodies; while virtually all the same people show up to APEC, the EAS and ADMM+ meetings.

At a basic level operations and resources need to be rationalised.

The other problem is that Asian states are happy to talk about security in a broad, non-committal sense but they do not trust one another enough to take further steps, even after years of discussions.

And security co-operation is very limited because many states are adopting policies that are almost entirely contradictory.

As their representatives attend seemingly endless security summits, states are taking steps to prepare themselves for worst case military scenarios through increased defence spending. That’s not the way to increase trust.

And let’s not forget that the sheer size of the US, China and India mean they will always dominate security discussions.

Problems for Australia

Australia has been a key player in efforts to develop and improve security co-operation in Asia, but it is a lead player in the region’s defence expenditure escalation.

Central to that process has been the long-running efforts to tighten Australia’s alliance with the US - something which hasn’t escaped Beijing’s attention. Efforts to drive co-operation in Asia will be limited by Australia’s own policy choices.

Trade won’t solve everything

The liberal ideal that trade and investment, together with international institutions will effectively damp down rivalry and reduce insecurity in international relations, but so far experience seems to be a case study refuting that theory.

Unless states have a significant change in attitude, an improvement in institutional design and an increase in investment, the prospects for security cooperation in Asia are not likely to improve anytime soon.

Australia, take note.

This is the second part of our Australia in Asia series. To read the other parts, follow these links:

- Part one: Is Australia ready for the “Asian Century”

- Part two: Australia in Asia: How to keep the peace and ensure regional security

- Part three: The lucky, lazy country shows how not to win friends in Asia

- Part four: How Australian aid in Asia can benefit those at home

- Part five: Learning to live in the Asian Century

- Part six: Colombo plan: An initiative that brought Australia and Asia together

- Part seven: Why Australia’s trade relationship with China remains at ground level

- Part eight: Finding the balance between India and China in the Asian ‘concert of powers’