The Federal government has recently announced six potential sites for a low-level nuclear waste repository: Sallys Flat in New South Wales, Hale in the Northern Territory, Cortlinye, Pinkawillinie and Barndioota in South Australia and Oman Ama in Queensland. The six were whittled down from an original list of 28 voluntarily nominated sites in a process set up under the National Radioactive Waste Management Act 2012.

The plan is to create a shortlist of three sites in 2016 and by the end of the year nominate the winning candidate. The site is scheduled to be open to receive Australia’s low-level nuclear waste by 2020.

Australia has been trying to construct such a facility for the past 35 years without success. Australia urgently needs a dedicated federal facility to deal with this waste since each year it produces approximately two swimming pools worth of low-level waste (40 cubic metres) and five cubic metres of intermediate-level wastes. There are now around 4,300 cubic metres of waste that needs to be housed.

So, will Australia finally get a nuclear waste site?

Australia needs a storage site

Low-level nuclear waste typically comprises items such as lightly irradiated paper, plastic, gloves, clothing, soil and filters typically generated by industry, hospitals and nuclear facilities.

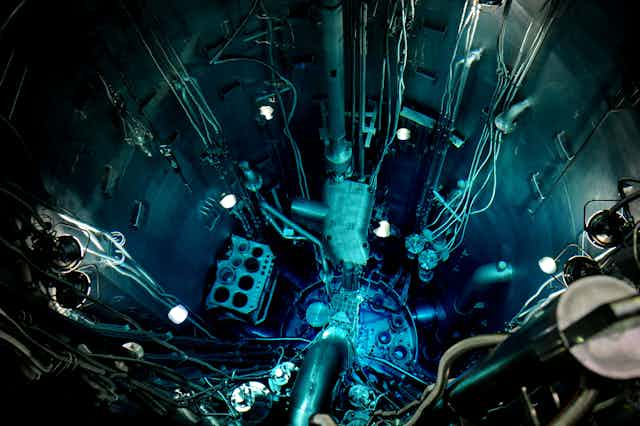

Such low-level waste has been stored for decades at 100 interim sites such as universities or hospitals across Australia while intermediate-level radioactive waste can only presently be stored at the Lucas Heights facility in Sydney.

The issue is particularly urgent for intermediate-level waste disposal since in the next year, 13.2 cubic metres of such waste, the byproduct of past contracts with France and Scotland, will need a home and the only currently available site is Lucas Heights.

Nuclear waste should be buried for at least several hundred years in a geologically stable area with a low water table and preferably away from population centres.

However, the Australian government has yet to be able to convince either state governments or individual landowners to host such a site. It has been unable to overcome a fierce backlash from local residents and environmentalists opposed to it being placed in their local area.

A brief history of the storage debate

From 1980 onwards, various Australian governments have attempted to site a low-level waste repository. (An intermediate waste site other than Lucas Heights has barely been mooted given the difficulty in siting even a low-level facility).

By 1992, a site near Woomera, South Australia was nominated. But that choice was abandoned by the federal government due to the intransigence of the SA government which, fearing a political backlash if it was built, refused to countenance a facility within its borders. While the federal government could theoretically have overridden state objections, it was not willing to pay the political price to do so.

In the face of state and territory opposition, the federal government changed tack and only sought out potential sites on Commonwealth land.

In June 2007 the indigenous Northern Land Council proposed an area at Muckaty, 120 kilometres from Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory, on behalf of some of the traditional owners. The federal government in September 2007 agreed despite the objections of the territorial government.

To induce the indigenous elders to agree to the siting, the government was willing to pay A$200,000 to the Northern Land Council, for the benefit of Lauder Ngapa Group members, set up an eleven million dollar charitable trust, and one million dollars for education scholarships for the benefit of that group.

But a coalition of other Aboriginal traditional owners of the land initiated Federal Court proceedings to challenge the nomination arguing that they had not been properly consulted nor had legally consented to hosting the site.

While the case was still ongoing the Northern Land Council and the Commonwealth government agreed to withdraw the nomination arguing the issue was proving too divisive among the local indigenous clans.

While the need for a low-level waste repository has never been greater, given the record to date, parties are unlikely to reach agreement by the government’s proposed date, if at all. By international standards, the government offers relatively low compensation to affected locals, which is unlikely to be an effective inducement to allow community acceptance.

Further, the government’s general inability to put in place an effective process for engendering societal and indigenous acceptance despite multiple attempts does not bode well for success.