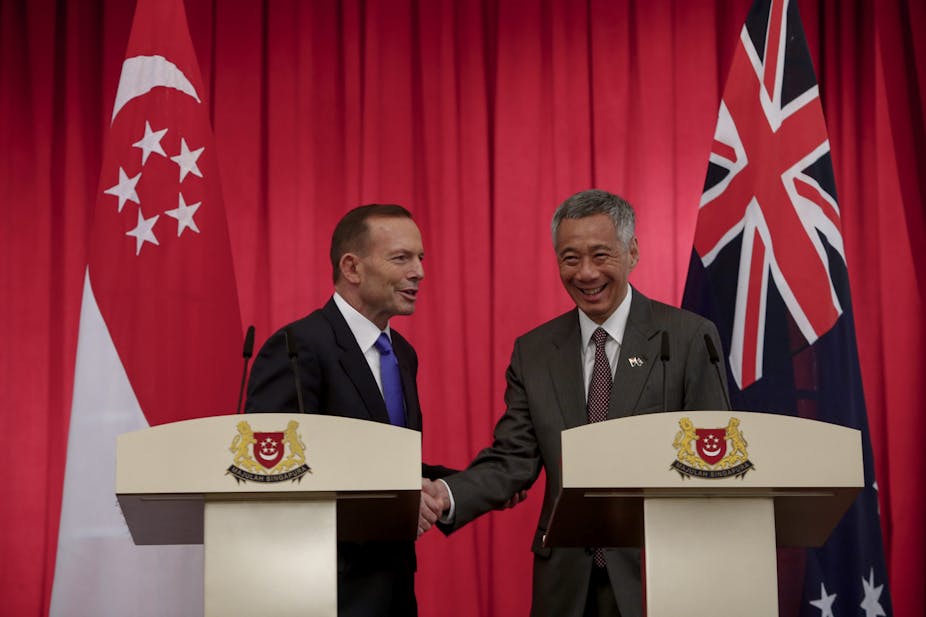

The signing of a comprehensive strategic partnership by Indonesia’s closest neighbours, Australia and Singapore, prompts some questions around how it may affect Southeast Asia’s biggest economy.

This agreement covers a broad range of aspects; not only economic, but also foreign policy, security and defence, moving the relationship between Singapore and Australia from an initial stage of simple trading partners to closer investment ties.

But concerns that this new bilateral partnership might splinter regional multilateral relationships are largely unfounded. Strengthening of the partnership between Australia and Singapore will not harm their neighbouring countries, including Indonesia.

Complementary rather than competitive

First, at the moment, regional trade agreements suit Indonesia. My recent study finds that, for Indonesia, the ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (FTA) is more suitable than bilateral FTAs.

In bilateral trade negotiations, Indonesia’s position is usually weaker than higher-income countries that serve as economic hubs. In relation to economic hubs, Indonesia’s position is more that of the spoke. Negotiating with other partners under the “regional umbrella” of ASEAN, despite being slow, is safer for Indonesia.

Second, the partnership will not mean Australia will compete with Indonesia in attracting investment from Singapore. Singapore and Australia have different productivity levels across economic sectors compared to Indonesia.

Singapore is one of Indonesia’s largest investors together with Japan, Korea, China, the United States and the European Union. It invests largely in transportation, storage and communication. Singapore holds an important position as an economic hub of service and supply-chain networks for Indonesia.

Meanwhile, Australia recently became one of the top ten investors for Indonesia. Its top three investments are in chemicals, mining and utilities.

Singapore and Australia are both high-income countries with a gross national income (GNI) per capita of US$54,040 and $65,400 respectively. Meanwhile, Indonesia is a lower-middle-income country with a $3,580 GNI per capita.

Third, the difference in levels of development and service sector competitiveness between Australia-Singapore and Indonesia indicates that they complement, rather than compete with, each other in their economic relations.

World Bank Data shows that in 2013 Singapore’s service sector amounted to 75% of the country’s GDP. Similar to Singapore, Australia depends on its service sector, making up approximately 71% of its GDP.

Indonesia also has a sizeable service sector worth around 40% of its GDP. But Indonesia reaps only around $23 billion per year, which is small compared to Singapore and Australia, which obtain $130 billion and $53 billion respectively.

Singapore’s economic role in Indonesia

Singapore and Indonesia are founding members of ASEAN. Singapore is one of the initiators of the ASEAN FTA, officially signed in Singapore in 1992.

Unlike the EU where its largest economy is a high-income country, ASEAN has the opposite: Indonesia is [ASEAN’s largest economy](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ASEAN_countries_by_GDP_(nominal) and is still a lower-middle-income country. Singapore, ASEAN’s highest-income country, has a smaller economy.

Singapore is the most advanced among ASEAN member states in forming bilateral trade agreements with non-ASEAN members. Yet such agreements in ASEAN have proven to be harmless for Indonesia.

Despite the Singapore-Australia partnership, economic ties between Singapore and Indonesia will continue to be essential, not only for the two countries but also for ASEAN.

Within the last 30 years, Singapore has always been among Indonesia’s top three trading partners. This will likely continue as Singapore serves as a hub in ASEAN’s economic network and is important for Indonesia’s trade and investment flows.

Australia’s economic role in Indonesia

Australia and Indonesia economic ties have increased particularly after Indonesia entered its reformasi (reform era) following the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998. Official visits involving the Australian prime minister and Indonesian president doubled between 2001 and 2014 compared to the pre-reform era of 1959-1996.

Australia has always been among Indonesia’s top ten trading partners and vice versa. Australia runs a trade surplus with Indonesia for food products such as cereal, sugar, meat, and dairy. Indonesia’s trade surplus over Australia is based mostly on wood, paper, rubber and fuel.

The two countries share complementary trade relations when it comes to iron, steel, cotton, clothing, precious metal and jewellery. Australia exports raw materials to Indonesia and Indonesia exports its final products to Australia.

Australia is also among the top tourism origin countries for Indonesia after Singapore and Malaysia. Meanwhile, Indonesian students have continuously been among the top ten foreign students in Australia.

Multi-country partnerships

Australia and Singapore are part of several multi-country frameworks such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement, East Asia Summit, the recent Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, as well as the long-standing frameworks of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum and the World Trade Organisation (WTO), of which Indonesia is a member.

The close relationship between Singapore and Australia should support their existing relations in multilateral arrangements. As former WTO director-general Pascal Lamy said about regional and multilateral relationships, they are “pepper and curry” both complementing each other – without one or the other, it will be a “disastrous dinner”.

Singapore and Australia should treat their partnership as a “building block” instead of a “stumbling block” for their multilateral partnerships.