It may be that there are no more shrews in Australia. There was only ever one representative, edging into the Australian political estate on the remote Christmas Island, closer to Java than any other part of Australia.

Shrews are an odd group of mostly very small placental insectivores, with nearly 400 species across Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas. In folklore, they have a reputation that is unwelcome, largely undeserved and sometimes simply bizarre: for associating with witches, for turning wine sour, and for ill-temper.

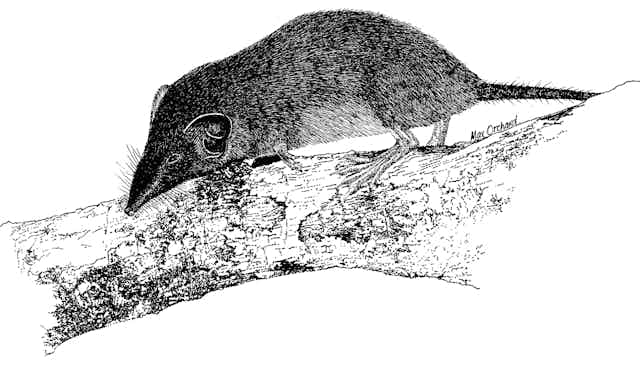

They resemble small long-nosed and small-eyed mice, but are unrelated to rodents. At 2 grams, the Etruscan Shrew is the smallest mammal in the world. In continental Australia, they have ecological counterparts in the unrelated marsupial planigales, ningauis, dunnarts and antechinuses.

The Christmas Island Shrew (Crocidura trichura) was long considered a variety or subspecies of a more widespread Asian species. However a recent genetic study by Mark Eldridge and others, based on the few now long dead individual specimens, has demonstrated that it is (or was) a distinct species, restricted to Christmas Island. It may be very cold comfort to the probably extinct shrew that its uniqueness is now verified.

Status

The Christmas Island Shrew is remarkably little known. Most of the knowledge of it comes from a few observations made at the time of its discovery, in the 1890s. Subsequent to 1902, it has been reported only four times, twice in 1958, once in 1984 and once in 1985. It was feared extinct by 1908, and considered extinct in the 1940s.

As evident from its fitful reappearances, extinction may be surprisingly difficult to prove, especially for small and cryptic species. Pessimists now conclude that it will not reappear; optimists cling to a flickering belief that there may still be a few individuals eking out an existence in the rainforest. Given the relatively small size of Christmas Island (135 km2), its existence is a puzzle that should be solvable.

The Christmas Island Shrew was once common. The extraordinary naturalist Charles Andrews was commissioned to undertake a comprehensive baseline survey of Christmas Island in 1898, soon after its first settlement, to chronicle the impact:

It has not hitherto been possible to watch carefully the immediate effects produced by the immigration of civilized man - and the animals and plants which follow in his wake - upon the physical conditions and upon the indigenous fauna and flora of an isolated oceanic island.

In 1900, Andrews wrote of the shrew:

this little animal is extremely common all over the island, and at night its shrill squeak, like the cry of a bat, can be heard on all sides. It lives in holes in rocks and roots of trees, and seems to feed mainly on small beetles.

No one since has added substantially to those two sentences.

Threats

Settlement has been unforgiving for Christmas Island’s unusually large collection of endemic species: three of its four other endemic mammal species are extinct, and the last remaining species (a flying-fox) is now threatened. Its five endemic reptile species have fared little better.

By Andrews’ next visit (in 1908) to monitor the island’s environment, changes had been drastic: the shrew had disappeared, along with the island’s two previously extraordinarily abundant endemic rat species, with the losses of the rats (and possibly the shrew) caused by disease (trypanosomiasis) brought in by a careless but fateful introduction of Black Rats. The native rats were never again seen. But obviously a few shrews persisted, with a small population surviving at least until the 1980s.

Strategy

How do you conserve a species that may or may not exist? Oddly, given that there have been no recovery plans for many threatened species known to be in need of them, the Christmas Island Shrew has been the subject of two recovery plans, in 1997 and 2004. These could as well be written for snarks, angels or unicorns.

However, they did prompt some targeted surveys, using pitfall traps, remote cameras and bat detectors (based on the assumption that these may record the shrew’s high-pitched squeaks).

To date, the searches have been futile; and current management is instead based on hope, that maybe one will turn up unlooked-for, or form the quest for a zoological Quixote.

Conclusion

Christmas Island is now an inhospitable place for many native species, with ecological transformation due to super-colonies of crazy ants, a high density of feral cats and black rats, and ongoing mining. In his 2002 book “The future of life”, the zoologist EO Wilson wrote of the existential twilight, that “thin zone from the critically endangered to the living dead and thence into oblivion”. This is likely the destiny of the Christmas Island Shrew.

The Conversation is running a series on Australian endangered species. See it here.