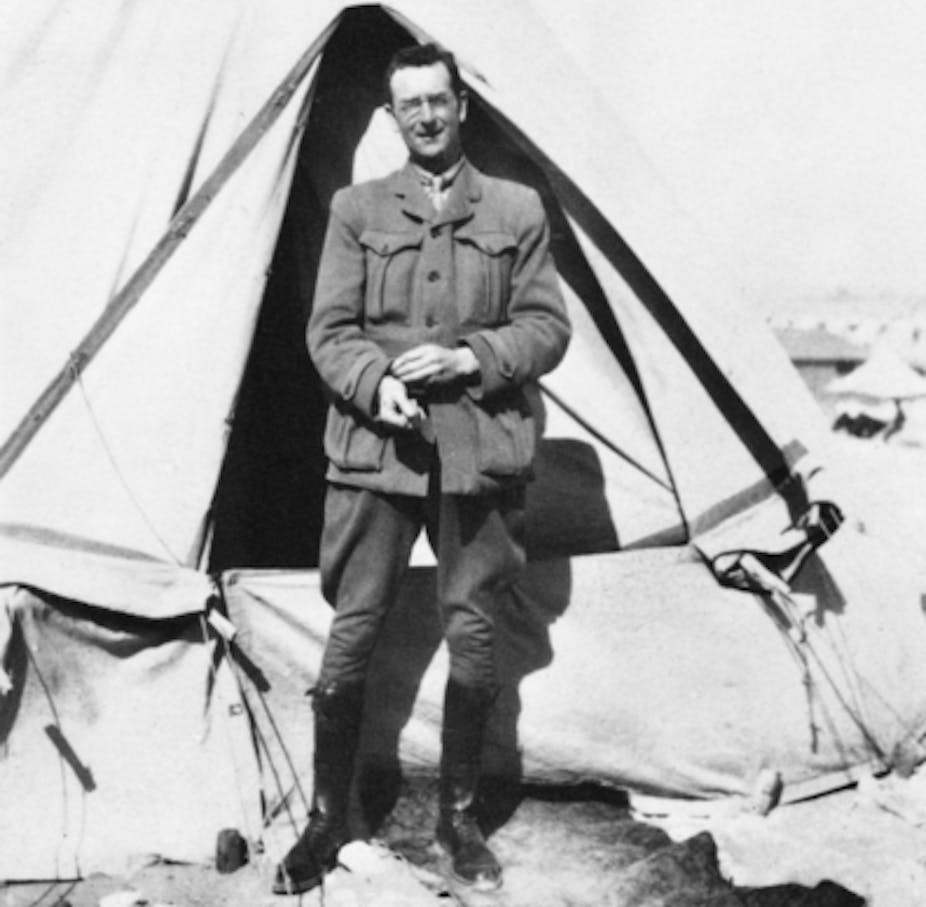

One man is central to Australia’s understanding of its protracted defeat at Gallipoli a century ago: C.E.W. (Charles) Bean, Australian War Correspondent, Official Historian and unofficial curator of the Anzac legend.

Bean’s overwhelming influence over how Australians remember Gallipoli, Anzacs and the Great War is undeniable and nowhere more evident than in his first Anzac publication – The Anzac Book. This was an anthology of stories, poems, cartoons and colour illustrations written and drawn by the Anzac soldiers while they were in the Gallipoli trenches.

For Bean, the archetypal Anzac was strong, resilient, inventive, good-humoured, laconic and duty-bound. This is not too far removed from the archetypal Australian bushman of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A quick look at Bean’s pre-war writing, such as his book On the Wool Track, provides a clear indication that he already had a strong idea of the Australian character even before he landed with the troops at Gallipoli in April 1915.

After the Gallipoli landing, the bushman’s character easily transformed into that of the Anzac soldier. Bean’s Anzac drew on the bushman’s colonial roots and continued to demonstrate strength in the face of harsh and dangerous conditions, all with good humour. However, this was just an ideal, conceived and promoted by a man with the means to do so and a personal investment in the commemoration of Anzac deeds.

How the book came about

Bean’s first opportunity to promote a comprehensive image of the generalised Anzac character presented itself in November 1915. A special committee was formed to produce an Anzac trench publication; contributions were solicited in a notice circulated to the population of Anzac Cove on November 14.

To encourage contributors, prizes were offered for the best submission in each category. All profits were to be used to benefit the Army Corps. In the end, 150 submissions were received – although not all of these were included in the final publication.

While it was originally conceived as an annual magazine, it became clear very quickly that the Allied forces would not remain on the Gallipoli peninsula much longer. In light of this, the publication was reconsidered as a souvenir of the campaign for a military and civilian audience.

After the Gallipoli peninsula was evacuated in December 1915, Bean and his assistant Arthur Bazley worked on the manuscript from a cowshed in Imbros, which they named the “Villa Pericles”. What resulted was The Anzac Book.

Bean selected submissions that promoted the everyday challenges faced by the Anzac soldier. For Bean, the simple act of completing ordinary day-to-day duties in the face of adversity was an act of heroism worth recording. Poems such as “To My Bath” and “Army Biscuits” related the ongoing filth and drudgery with good humour and light-heartedness. It was the dignity of facing the horror of war with an easy-going nature that Bean was keen to present as heroic.

What was left out

However, the submissions that Bean excluded were just as important to the construction of The Anzac Book as the submissions he included. Bean was a meticulous editor. The nature of the final publication owes much to his alteration and rejection of the works submitted.

Bean had a tendency to omit anything that had exaggerated sentiment, or anything that dealt with the harsh realities of war without humour. He specifically rejected items that included anything grotesque, discussed the crippling fear of war, deserting soldiers, or included descriptions of extended tedium.

Bean also rejected a number of poems that presented Anzac soldiers in more traditionally heroic ways, and/or the history-making nature of the campaign. He preferred to highlight the witty and more down-to-earth accounts of the Gallipoli landing and occupation.

Although The Anzac Book presented a specially crafted image of the Anzac soldier, Bean did not want the historical record altered because of selective editing. In February 1917, he wrote to the War Records Office with a suggestion that important documents – such as The Anzac Book manuscript – be preserved so that they could one day be deposited in a museum.

This request was granted. The rejected submissions can be viewed in the Australian War Memorial archives today.

The book’s significance

Bean was sure that The Anzac Book would hold a place of significance in the Australian historical record. In anticipation of its importance, he reserved several hundred copies of the book for Australian libraries and museums.

After publication, Bean spent the next three years tirelessly distributing copies to soldiers, officers, civilians and anyone else who could be convinced to buy a copy. Almost half of the copies ordered by the AIF’s First Division were sent home to Australia. This trend continued as more copies were ordered on the front lines in France and Belgium.

In September 1916, the publisher recorded 104,432 book sales, of which 53,000 were to the AIF. Before the end of the war, almost every Australian household would have had access to a copy of The Anzac Book. The third edition of The Anzac Book was published in 2010 and is still being purchased in 2015.

Bean’s vision of the Anzac soldier has dominated historical memory for nearly 100 years. For that reason, The Anzac Book is crucial to understanding how Australians conceptualise their ideal national character.

As we pause to reflect on the Gallipoli landings, we might think about Bean’s omissions and the reasons behind his editorial decisions to eliminate the bloody realities of war in favour of a specially crafted and idealised construction of the Anzacs and the Gallipoli campaign.

Whether Bean’s edits were made to build morale or even to construct a legacy, that he made an effort to preserve what was excluded in 1915 for the historical record is significant and worth revisiting.

You can listen to Sarah Midford speak about Charles Bean and The Anzac Book below, in a podcast produced by La Trobe University.