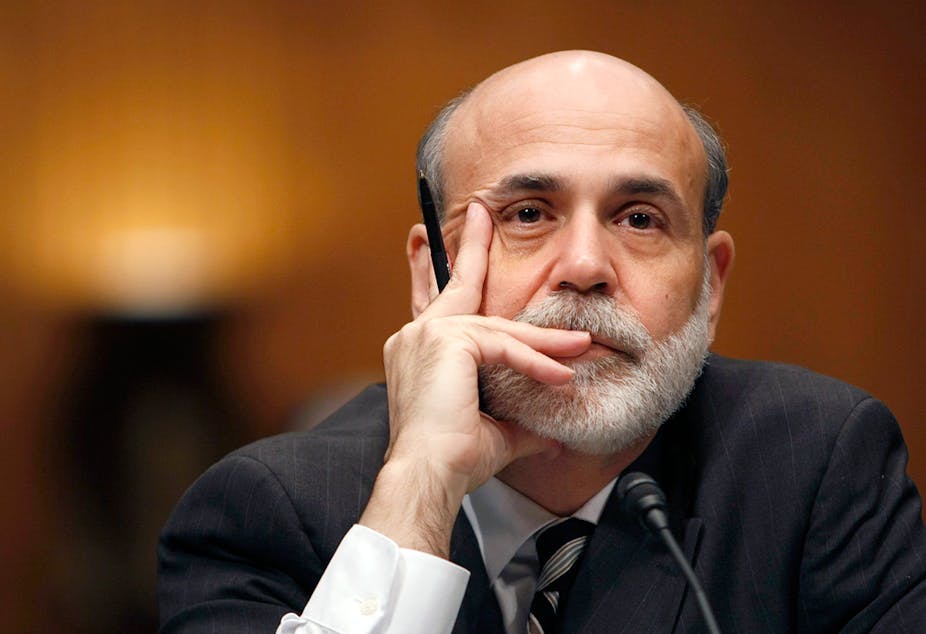

It’s clear mortgage standards have gotten too tight when even a former Federal Reserve chairman who makes as much as US$250,000 per speech cannot refinance his home.

Ben Bernanke complained about his inability to get a new mortgage on his Washington, DC, home during conference in Chicago last month. “I recently tried to refinance my mortgage and I was unsuccessful in doing so,” he said during a Q&A with economist Mark Zandi. The audience burst out laughing, prompting Bernanke to respond: “I’m not making that up.”

Clearly the underwriting rules and practices that determine whether or not an applicant qualifies for a home mortgage are much stricter today than they were before the financial crisis. As a result, the housing sector is not providing the economic stimulus we had come to expect during periods of economic recovery.

In part, the tightening reflects market changes that make mortgage loans riskier than they were before the crisis. The major factor was the nationwide slump in house prices between 2006 and 2009, the first such decline since the 1930s.

Good bye to the liberal lending of [PRE-CRISIS YEARS]

The very liberal terms that prevailed prior to the crisis were based on a widespread belief that such declines were a thing of the past. When housing prices are only going up, it is very difficult to make a bad mortgage loan. Now that the market re-learns that house prices can decline, mortgages become riskier.

A second factor has been the post-crisis practice of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to require lenders that originate loans for sale to them to buy the debt back if the homeowner defaults too quickly. This has caused many lenders to impose underwriting rules that are more restrictive than required by law and regulation.

A third factor has been a post-crisis tightening of underwriting standards imposed by law and regulation. The riskier mortgage types that experienced the highest default rates are no longer permitted. This includes loans that allow negative amortization in which the payment does not cover the interest, and loans that allow interest-only where the payment covers only the interest. Monthly payments today must be fully-amortizing, meaning that if continued through the life of the loan, the balance will be paid off at term.

In addition, riskier loan features that are still allowed carry a larger penalty than they did before the crisis. For example, a borrower refinancing with “cash-out” – in which a borrower replaces an existing mortgage with a larger one, pocketing the difference – is subject to a larger price penalty than a normal refinancing compared with before the crisis, and may also be subject to a higher credit score requirement, a higher equity requirement or both. The same is true of loans on 2-4 family properties and condos, relative to loans on single-family homes.

A knee-jerk response

But the tightening of underwriting rules following the crisis has gone beyond these rational adjustments to a riskier environment. It also included knee-jerk responses to pre-crisis abuses, particularly to the many cases of loans granted to people who obviously couldn’t repay them. A system of hastily enacted rules and procedures designed to prevent this from recurring are now blocking many good loans from being made.

The following are major features and flaws of this system:

Underwriter discretion is substantially narrowed. Rules have largely eliminated discretion, and the major role of underwriters today is to check for conformity with the rules.

A belief that all mortgage loans should be affordable. In fact, there are numerous circumstances in which an unaffordable loan is in the interest of a borrower and compelling evidence exists that the loan will be fully repaid.

One example is an owner who wants to remain in the house for a few years before selling and needs a cash-out refinance to make the payments. Underwriters should be able to rely on their own good judgment in such cases. But these instances are now not allowed in the new system.

Ratios of debt-to-income above 43% indicate over-commitment by the applicant. Given the wide range of circumstances that can affect a borrower’s capacity to meet obligations, fixation on any ratio as a maximum makes no sense. But again, an underwriter should have the discretion to make a call, and that no longer exists.

The affordability requirement is absolute and not affected by the applicant’s credit score or equity in the property. Applicants might be turned down even if they are making a very high down payment of 40% and possess a superior credit score of 800 if their income is not adequate. This makes no sense, and was the reason Bernanke had trouble.

Income must be fully documented. Prior to the crisis, documentation requirements ranged from full-doc to no-doc, with three or four partial- docs in-between. The less complete the documentation, the higher the price and the larger the required equity and credit score. That sensible system is now gone and all loans must be fully documented. This is why I keep getting letters from self-employed applicants who cannot qualify despite having large equity and a high credit score.

Much of the system of rules and beliefs described above stem from Dodd-Frank, and were formulated in an atmosphere hostile to lenders. But borrowers are the ones paying the price.

The issues need to be reconsidered in an atmosphere free of vindictiveness toward lenders. It could begin with Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and their supervisor the Federal Housing Finance Agency, which could re-examine their rules, identify those that should be liberalized, and determine which they could fix on their own and which would require new legislation.