Today the first international retrospective of Indian artist Bhupen Khakhar’s work opens at Tate Modern. This is, as Atul Dodiya, a close friend and fellow artist recently stated, “a moment of great pride and joy” and it is not hard to see why. The show is a thoughtfully curated and well-researched display of works and writing from five decades of his multi-disciplinary career – Khakhar died in 2003. And beyond its visual allure, the show raises questions about art in India today.

The exhibition opens ahead of the new Tate Modern extension on June 17 and leads what Frances Morris, Director of Tate Modern, described as “the new spirit of a bigger international story”. It is no coincidence that one of Khakhar’s arresting works, Bullet Shot in the Stomach (2001), was also there during the opening year of the Turbine Hall. His work is beguiling.

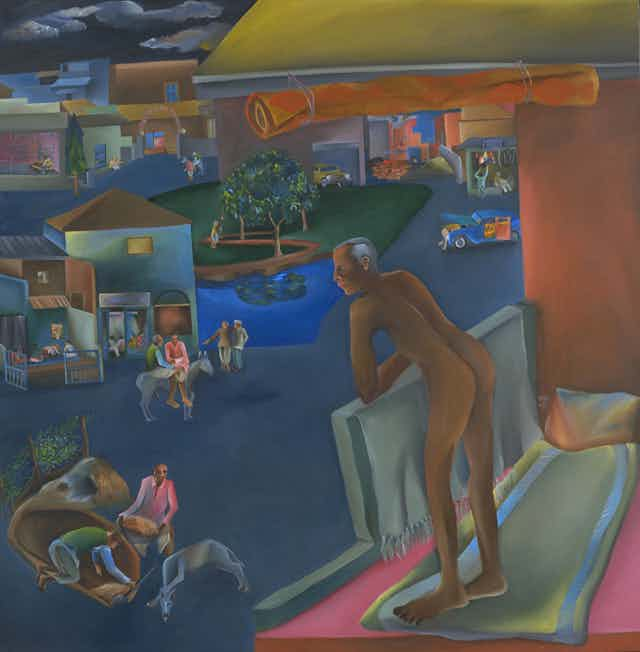

On one level it is colourful and appealing, calling the viewer closer towards its rich pigment and expressive figures. But once close to the work, Khakhar’s consistently frank, bold and intelligent exploration of Indian culture becomes apparent.

The playful and humorous style which coheres the show is a way for the artist to lead into harder questions. This guise allows Khakhar to confront uncomfortable topics including religious worship, homosexuality and India’s political consciousness. Paintings such as Muktibahini Soldier with a Gun (1972), featuring a Bangladeshi freedom fighter and Yayati (1987), which portrays a mix of homoerotic and religious iconography, are provocative. Many works have not been on public display in India.

This should therefore been seen as a valuable show which foregrounds Khakhar’s strength of character and unwavering honesty, something The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones sadly failed to see.

Artistic struggle

Khakhar struggled to establish himself as an artist since his family did not see it as an acceptable career. For approval he worked hard and completed an economics and accountancy degree before attending printmaking night classes, and eventually completing a masters in art criticism at MS University of Baroda in 1962.

Although Khakhar’s accountancy qualification gave him the financial security to continue his practice, it also made him aware of the lack of formal facilities and limited funding for other artists. He held informal gatherings at his home, the “open air theatre” – a part of which is replicated in the second room at the Tate’s show – where international artists including Howard Hodgkin and his close friends such as the critic Geeta Kapur gathered.

This salon format was essential to his work and Khakhar was reflexive about how art was regarded in India. In his final interview, he spoke about the challenges which artists faced and the why it was difficult to establish a legitimate practice:

Unlike in the West, where they live alone from a young age, we are more dependent on our family structures here. The close-knit family also makes you not just servile but timid in many ways because you are answerable to a larger network of people for whom you care. This prevents you often from taking the individualist positions so important to art.

Opportunities today

Khakhar’s observations and experiences still have relevance, as Michael Knowles, Director of The Creative Hub at Sushant Schools of Design, discussed with me recently. He stated this week that while enrolment figures for art and design students are increasing, the intake typically lack confidence and “have an insecurity which comes from being told by parents and teachers at the age of 12: ‘Throw away your sketch books and pencils, you don’t need art to a be a doctor, lawyer, banker’.”

It may be surprising how far this attitude spreads. Concerns raised last week by one of India’s leading artists, Bose Krishnamachari, show that the arts are in need of championing. His public statement to Kerala’s Chief Minister emphasised this and called for there to be pride in India’s culture:

Our arts, visual, performative and the written word are as strong as that of any other, if not superior. We need to accept it, promote it, live by it so that it lights a thousand candles that act as the beacon for future generations.

This message is urgent and emotive. There is growing cultural censorship in India and as Roobina Karode, Director of Kiran Nadar Museum of Art confirmed to me recently, there is a poor ratio of funds compared to the wealth of India’s talent. But with figures such as Krishnamachari around, there is optimism. As Karode continued, “artists are developing innovative ways of gaining exposure and Indian art is becoming global”.

Another artist who is driving this momentum is Nikhil Chopra, who on May 30 completed a 90-hour performance at London’s South Bank Centre. In a recent interview, he spoke to me about the value of artist-run project spaces such as Khoj, set up in 1997 in New Delhi, and Heritage Hotel. Similar to the Kasauli Artist Workshop which Bhupen attended in 1976, these adopt a residency format which provides artists with studio space, a place to exchange ideas, and gives their work exposure, which might not otherwise be available.

These initiatives are vital and have been invaluable to a number of artists including the popular duo Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra. But more is needed to help build and maintain a strong infrastructure for Indian artists. This will in part rely on engagement which encourages those who are new to art to understand that it is an important medium. As Khakhar’s spectrum of works show, art has much more than aesthetic impact; it raises questions, changes perspectives and can articulate challenging ideas.