Another game, another bite. That’s the allegation against Uruguayan Luis Suárez, anyway, who has been accused of sinking his teeth into an opposition player. For the third time.

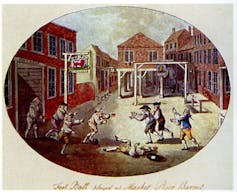

But a mid-game nibble on an Italian player’s shoulder is nothing compared to football’s ugly past. There is a blood-red thread running through the early history of the beautiful game.

From kickabouts with the heads of defeated enemies, to stabbings, players getting kicked unconscious, mass brawls and broken bones, football rightly once had a well-earned reputation as “nothing but beastly fury and extreme violence”, as it was described by 16th century diplomat Thomas Elyot.

Severed heads

Like the wild Irish, I’ll ne’er think thee dead

Till I can play at football with thy head

– John Webster, The White Devil, 1612

About the time of the French Revolution some footballers from Kingston-upon-Thames were taken to court for participating in a riotous game on Shrove Tuesday. Their defence was that, in the distant past, a Viking raid had been defeated by townsmen. The invaders’ captain was killed and his head kicked around like a football. The judge accepted that the Kingston footballers’ game was an “immemorial custom” – and acquitted them.

This was of course a legend. But on the eve of the English Civil War a Catholic missionary priest was hung, drawn and quartered in Dorchester. The local butcher botched the job and the priest was put out of his misery by decapitation. A mob then got hold of the head and used it as a football for several hours. Exhausted by their entertainment they eventually put sticks in the eyes, ears, nose and mouth and then buried it near the body. They didn’t stick the head on the town gate because they feared an outbreak of plague – possibly as divine retribution for their actions.

Fatalities and serious injuries

Coroner’s inquests are a good source for telling us how football players were killed. Interestingly, in many cases the verdict was death by misadventure. Framing these incidents as accidents suggests players knew the risks involved.

Yet on some occasions men were also plainly murdered: perhaps in the heat of the game, perhaps using football as cover to settle long-standing quarrels. So we hear of players dying from a knee to the belly, a punch to the breast and being pushed or tripped to the ground. One had his nose and face smashed in by a ¼ pound stone. Another was stabbed in the upper arm and died the following week from infection. Several died from running on to sheathed knives.

And in one late 16th century incident tied up with witchcraft, we learn of old Brian Gunter of Berkshire drawing his dagger and using the pommel to smash two men’s skulls. They died within a fortnight.

Documents that constituted part of the everyday business of various secular and ecclesiastical courts can also reveal a great deal about the dangers of football. Thus on 25 February 1582 at a game in Essex an attacker collided so violently with the man guarding the goal that the goalkeeper was knocked unconscious. He died that night.

Then there was the 17th century aristocrat who passed out from a blow to the chest during a game played against another Lord and his servants. Three months later he was bedridden. The cure: a pipe full of tobacco. The smoke got in his lungs and he soon vomited up bits of congealed blood.

Other players merely escaped with broken legs. Sometimes they recalled their injury had been sustained at a celebratory game, usually played after a baptism or wedding. One labourer complained that he had lost his livelihood from a football-related injury. But another claimed to have been miraculously cured when he saw King Henry VI in a dream.

Brawls

Football’s potential for riotous behaviour was constantly noted by the authorities. On occasion games were just pretences to attack others from different communities.

Our best evidence for these social tensions comes from fights that marred regular “town and gown” matches. Hence around 1579, Cambridge University players were picked on by some townsmen of Chesterton. The latter provoked a quarrel and then began hitting the students with staves they had hidden in the church porch. When the scholars appealed to the local constable to keep the peace he ignored them – and cheered on the townsmen. Desperate for their lives (one student was chased by a spear-wielding servant) they ran away.

At medieval Oxford meanwhile, a student playing ball in the High Street was reportedly attacked and killed by Irish students.

Accidents

There were other ways to die. One 14th century Londoner got out of a window to retrieve a ball trapped in a gutter. He slipped and fell, and died from his injuries.

Equally unfortunate were the lads who one January Sunday 1635 played a game on the frozen River Trent near Gainsborough. During a scuffle the ice broke and eight were drowned – much to the satisfaction of Henry Burton, a puritan moralist who used this as an example of God’s judgement on Sabbath breakers.

Disapproval

Unsurprisingly football was frequently condemned. One hostile 15th century observer condemned it as “more common, undignified, and worthless” than any other game he had witnessed – especially since it seldom ended without injury or accident.

Weighing up the pros and cons, a 16th century physician also felt football wasn’t worth the risks. A healthy, well-exercised body wasn’t much use with a fractured shin or broken leg.

The last word, however, goes to an Elizabethan pamphleteer named Philip Stubbes. Football, he protested, should be considered a “friendly kind of fight” rather than a game or recreation; a “bloody and murdering practise” rather than a good-humoured sport or pastime. Nothing good came from it. Only “envy, malice, rancour, choler, hatred, displeasure, enmity” and who knew what else.

Can the same be said of today’s football? Well, thankfully we have rules. But still, football retains a violent streak, as Luis Suarez and his contemporaries constantly remind us. Thank goodness for the referee.