Only when one has lost all curiosity about the future has one reached the age to write an autobiography.

Evelyn Waugh was only 60 when he wrote this downbeat opening to his memoir, A Little Learning. For ten years he’d struggled with deep depression, relying heavily on alcohol and prescription sedatives and putting all his energy into a talent he believed was fading.

He was wrong about that – two novels of the acclaimed World War II trilogy Sword of Honour appeared during this decade of despair – nevertheless, Waugh had turned his back on the material world by the time his autobiography appeared in 1964. It was intended as the first volume of a longer work but he died before its sequel, aptly named A Little Hope, was finished. He suffered a massive coronary thrombosis at his home on April 10 1966. He had just attended mass and his favourite daughter, Meg, believed he’d been praying for death.

Suspicious of the modern, Waugh looked instead for comfort in the past. A preface to his most famous novel, Brideshead Revisited (1945), explains that when writing the book Waugh had assumed the way of life it portrayed – old established families living on in ancestral homes for generations – was dying out. And just as Waugh looked back to 1925 for Brideshead, in A Little Learning he looked even further back – through his own forebears, his “idyllic” childhood and miserable boarding school years – before emerging into the bright sunlight of 1920s Oxford.

Bright Young Things

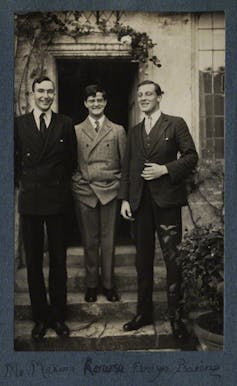

At university Waugh was dazzled by a glamorous world totally unlike anything he had known before, adopting a sophisticated set of young bohemians known as the Aesthetes. Like many freshers, young Evelyn celebrated his freedom by getting drunk and embarking on relationships with other undergraduates. He fell in love first with Richard Pares, a talented historian later “rescued” from debauchery by a concerned don, then Alistair Graham, who inspired Brideshead Revisited’s Sebastian Flyte. In A Little Learning Waugh gives Graham the pseudonym Hamish Lennox, the “friend of my heart”.

Waugh claimed to do minimal work at Oxford and, as far as his history degree was concerned, this is woefully accurate. But though often hungover, he was rarely truly idle. Waugh had written since he was a child, and as a student contributed regularly to university magazines – not only fiction but also write-ups of union debates and, perhaps surprisingly, some fantastic graphic art that captured the dynamic spirit of the times in which he was living.

Work was happening below the surface, too. The story Waugh tells of his friend Alfred Duggan during those years runs parallel to his own experience:

His memory was exceptionally retentive and in the shadowy years when he [drank] very heavily and [sat], apparently stupefied, turning the pages of an historical work in the library … his brain … was in an inexplicable way storing up recondite information which became available when he heroically overcame this inherited disability.

Decline and Fall?

Waugh barely went near “an historical” work at Oxford. But he read people. All he met were likely to find themselves preserved and transformed in the pages of his novels.

The testosterone-charged aristocrats of the Bullingdon Club become the “Bollinger club” in Decline and Fall (1928), Waugh’s first novel. These sons of “the English county families”, “baying for broken glass”, relieve Paul Pennyfeather of his trousers in the college quadrangle and so trigger his subsequent (mis)adventures. Similar “hearties” are responsible for Anthony Blanche’s leap into the Mercury fountain in Brideshead Revisited. Blanche is widely thought to have been based on Harold Acton, the flamboyant and cosmopolitan leader of the Aesthetes, but Waugh insisted that he much more closely resembled Brian Howard, a highly dubious student friend.

Paul Pennyfeather, too, was a type – though not one with whom Waugh had very much to do after his first, studious love Richard Pares. Some people really were at Oxford to live quietly and work for their degrees. The acclaimed left-wing historian AL Rowse, for example, was Waugh’s exact contemporary at Oxford, but treated his time there rather differently.

Both boys held history scholarships but, while Waugh left without completing his degree, Rowse was awarded the second highest mark in the whole year. In the University of Leeds’ Brotherton Library, which boasts a fantastic collection of Evelyn Waugh artefacts, it’s possible to follow the caustic comments Rowse scribbled on his personal copy of A Little Learning. “BFs” – short for “Bloody Fools” – appears frequently in the margins, and where Waugh observes that his generation were regarded by history as “libertines and wastrels”, Rowse’s tart note reads simply: “They were.”

In his first term at Oxford, Waugh recounted a “subdued” happiness in adopting a sober and restrained undergraduate life. “A pity he didn’t continue,” opines Rowse. But what if he had? Could Waugh have written Brideshead Revisited if he had never loved Graham, or created Anthony Blanche without meeting Acton and Howard?

Rowse, son of a clay miner and holder of the “one miserable university scholarship for the whole county of Cornwall”, had every right to resent what he saw as Waugh’s wasting of an opportunity for which he, Rowse, had fought hard. But there was more than one kind of education on offer in Waugh’s Oxford; and in his case, a little learning was quite enough to engender a rich legacy of comic, lyrical and unforgettable works.