If the Brexit negotiation process is doing one thing for British politics, it’s in shining a very bright light on the strategic manoeuvring of politicians on all sides. And simple game theory can tell us a lot about how the process is playing out among the different factions in parliament.

Many different games have been played so far, including elements of chicken and brinkmanship. There has been persuasion and negotiation and commitments and threats. Some of the promises have been empty, others more credible.

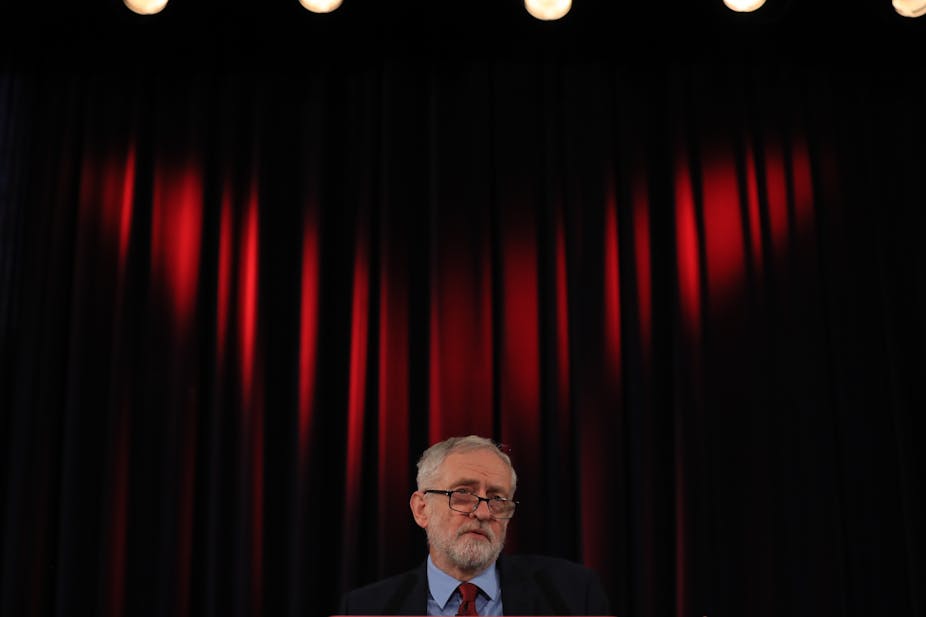

But nowhere is the strategic manoeuvring more clearly demonstrated than in Jeremy Corbyn’s current position that he will not enter into talks with Theresa May until no-deal Brexit is off the table. This is arguably the most important game to be played so far – and one which will be decisive for the eventual outcome, whatever that might be.

The game between May and Corbyn

In game theory, every game is fundamentally underpinned by the objectives of its players. It’s reasonable to assume that Corbyn’s main objective is to be prime minister. He will of course have subsidiary aims but this main objective will drive his substantive actions, strategies and positions. And to achieve it he needs to force a general election.

For May, further to her commitment that she will step down as prime minister before the next general election, it’s reasonable to assume that her main objective is to deliver on the 2016 referendum result – that is, to deliver Brexit, in some form. A subsidiary objective is likely to be to do so in as orderly a manner as is possible. But, it’s not unreasonable to assume that she may even contemplate some variant of a no-deal Brexit if that were the only way to get Brexit through parliament.

Some games also have a history and context. The history of the game currently being played between the prime minister and the leader of the opposition has four core elements. First, May’s withdrawal deal was massively defeated in parliament. Second, she survived a no-confidence vote in her government. Third, she now has limited time to amend or revise her deal and to try to get that revised deal through parliament. And fourth, she has now put an offer on the table to talk with various MPs to try to find a way forward.

However Corbyn has refused to engage in these discussions, instead stating his position that he will not talk unless the prime minister rules out a no-deal Brexit. The application of the principles of game theory can again tell us a lot about the strategic value of this.

A no-deal scenario

If the government said it would not tolerate a no-deal Brexit, eurosceptic MPs would likely unite very strongly against the prime minister. This would in turn drive further division in the Conservative Party, possibly beyond repair, making the party sufficiently weak to give Corbyn his best shot at winning a general election.

Of course, all of this is known to both May and Corbyn. And therefore at this point in time, there is absolutely no reason that the prime minister will take a no-deal Brexit off the table.

What next?

Over the coming weeks, May will need to decide between two broad strategies: either to relax one or more of her red lines, and agree to a relatively softer Brexit; or to stay close to her current deal, but with sufficient changes to satisfy the DUP MPs and the eurosceptic MPs in her party. Her preferred approach at the moment, it would seem, is to get Brexit through parliament with the support of these very eurosceptic MPs and the DUP members.

However, this is far from a done deal and so far this strategy hasn’t worked. But she’s likely to try again, in the coming week or so, to try to find a way to get them on board. But if her second attempt fails to get a slightly revised version of her deal through parliament – currently scheduled for January 29 – she may then consider the alternative approach of relaxing one or more of her red lines and repositioning towards a relatively softer form of Brexit.

At that point in the dynamic game, she may very likely want to give in to Corbyn’s condition of taking no-deal Brexit off the table. But, alas, at that point, he’s likely to call another vote of no confidence in her government, which she may lose as the eurosceptic Tory MPs (and even the DUP MPs) may either vote against her or, at best, abstain. And in that case, a general election is likely to follow.

So, in a nutshell, Corbyn’s strategy that he will not talk with the prime minister unless she takes the no-deal Brexit off the table gives him the best chance to force a general election, which, if achieved in the coming weeks, would also provide his best chance to win it.

As to whether it will work out, that’s difficult to predict. It goes without saying that many political games are high risk. Compromise is necessary to reach any agreement in life, and in any context – and that fundamental principle of negotiation applies in the context of the current Brexit impasse too. Both the prime minister and the leader of the opposition will have to compromise in some way at some point. How far down the road we get before they each play that strategy remains to be seen.