What a tragedy – that picture of the old father and the three sisters,

trembling day and night in terror at the possible deeds of this

drunken brutal son and brother!

That is the part of the life which affects me most.

George Eliot’s reaction to Elizabeth Gaskell’s dramatic account of Branwell Brontë’s malign effect on his family shows the stark difference between tranquil and industrious images of their home at Haworth Parsonage and the claustrophobic reality.

Branwell’s spiralling addictions to drink and drugs transformed Haworth at times from a well-ordered home to a domestic prison isolated by shame and fear. His behaviour became so dangerous that his father felt compelled to insist they share a bedroom after Branwell drunkenly almost set fire to the house. He was saved by Emily who flung him bodily from the bed and put the fire out with a large pan of water from the kitchen.

Branwell, the Brontë sisters’ talented but disturbed brother, has long stood in his siblings’ shadow, best known as a running joke in Stella Gibbons’s Cold Comfort Farm in which smug academic Mr Mybug tries to prove that Branwell wrote the sisters’ novels while hiding their outrageous drinking.

However, the bicentenary of Branwell’s birth has prompted a re-evaluation of his writing, biography, and influence on his famous sisters’ work.

Branwell’s regular boozing at his all-too-local local, The Bull public house in Haworth, contributed to his early death, masking symptoms of the tuberculosis which claimed his life in 1848.

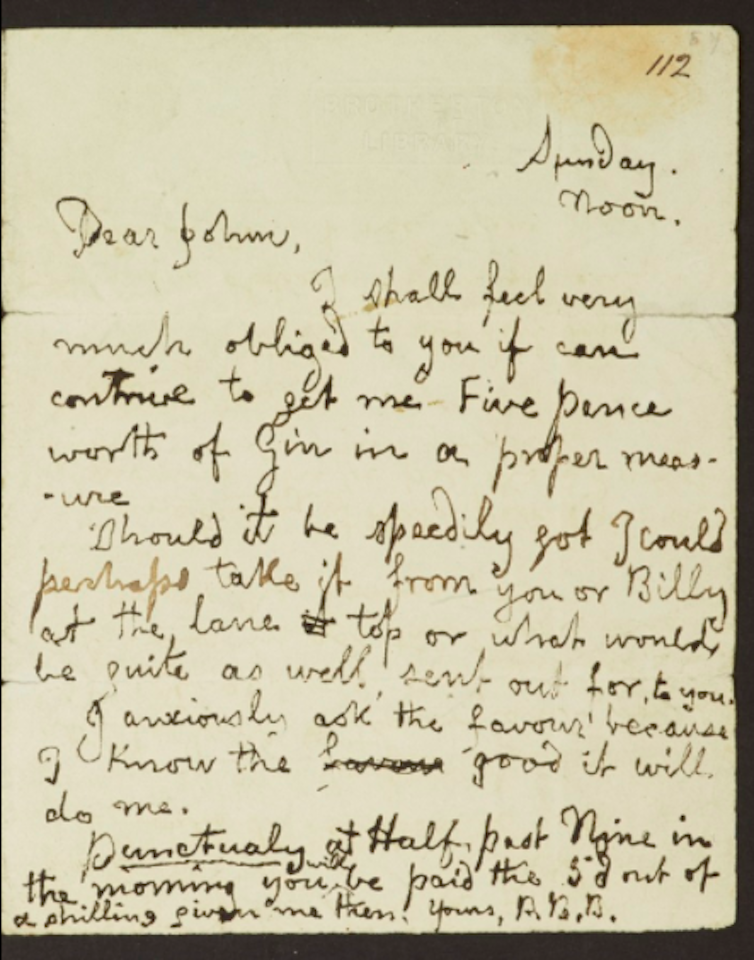

His final letter begs his friend, John Brown, to bring him gin:

Sunday. Noon.

Dear John,

I shall feel very much obliged to you if can contrive to get me Five pence worth of Gin in a proper measure.

Should it be speedily got I could perhaps take it from you or Billy at the lane if top or what would be quite as well, sent out for, to you.

I anxiously ask the favour because I know the favour good it will do me.

Punctually at Half past Nine in the morning you will be paid the 5d out of a shilling given me then. yours, P.B.B.

Branwell’s anxiety for drink in this letter is intense. His specific directions about collection only half hide the secrecy of his request (he would not wish his father to find out). Thirsty for alcohol, Branwell asks his friend to ensure that he gets maximum amount of gin for his money by stipulating “proper measure”.

As Branwell’s illness progressed, the sisters were writing and publishing their most famous novels: Charlotte’s Jane Eyre (1847), Emily’s Wuthering Heights (1847), and Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848). But how did his drunkenness and attacks of delirium tremens – generally attributed to symptoms related to the excessive consumption of alcohol in the 1840s with symptoms including high fever, trembling of the limbs, and hallucinations (“alcoholism” was not coined until 1859) – influence the sisters’ writing? And to what extent do other sources account for their novels’ frequent focus on drinking and drunkenness?

A history of drinking

Branwell’s drinking became problematic in 1845, following a psychological crisis arising from his relationship with his employer’s wife, Mrs Robinson. Scholars disagree about whether the young Branwell actually had an affair with the lady of the house, or his love was unrequited. Whatever you believe, he and others blamed this crisis for his later dependence on drink and drugs.

In Wuthering Heights and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Hindley Earnshaw and Arthur Huntingdon drink like Branwell. They behave erratically and offensively, exhibiting violent and suicidal tendencies. Many reviewers were disgusted, complaining about “drunken orgies” in Wildfell Hall and “scenes of brutality” in Wuthering Heights. Defending herself in the preface to the second edition of Wildfell Hall, Anne wrote that she felt a responsibility to “reveal the snares and pitfalls of life to the young and thoughtless traveller”. The original thoughtless traveller was Branwell; the novels were written and published in the year before his death. Disturbingly, both fictional characters die wracked by mental and physical agonies, yet feel compelled to drink to excess to the end.

Victorian drinking

The two novels’ bleak account of the fate of the heavy drinker goes against much contemporary received medical and temperance wisdom. Popular and medical thought about drink was changing. Moral theories of “drunkenness as vice” were challenged by medics such as Thomas Trotter and Robert MacNish, who proposed that drunkenness could be a disease which might be “cured”.

The sisters are likely to have read MacNish, who also wrote on a passion of theirs: phrenology. Medical descriptions of problem drinking by MacNish and Thomas Graham, author of their father’s medical reference book, are echoed in the sisters’ writing. For example, in Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff’s description of Hindley’s death suggests apoplexy, a condition commonly associated with habitual drunkenness:

We broke in this morning, for we heard him snorting like a horse; and there he was, laid over the settle - flaying and scalping would not have wakened him - I sent for Kenneth, and he came; but not till the beast had changed into carrion - he was both dead and cold, and stark.

Heathcliff’s grotesque description of Hindley “snorting like a horse” matches Dr Graham’s descriptions of stertorious breathing as a symptom of apoplexy. Emily’s choice of animalistic and undignified terms for Hindley’s death, particularly in comparison with Heathcliff’s controlled and smiling death, de-glamourises excessive drinking and reminds the reader of its stark medical consequences.

Through fiction Anne also sought to reveal coarse truths about male drunkenness. In The Tenant of Wildfell Hall Helen Huntingdon’s changing attitude to her ability to “cure” her husband of habitual drunkenness goes against the advice of temperance writers. Joseph Livesey, co-founder of the first teetotal society in Britain, recommended that “young girls make a declaration against drunkards”. His explanation is typical of early Victorian temperance and religious rhetoric:

I know no department in our social economy where the women have not great influence, and I cannot but think that lessons of morality, supported by their example, and delivered with earnestness and with the insinuations of female talents, would be productive of the happiest results.

Helen marries Arthur intending to save him, and so live up to the role allocated to women by writers like Livesey. However, it is not long before she appeals to her husband: “Don’t you know that you are a part of myself? And do you think you can injure and degrade yourself, and I not feel it?”. Soon after she describes him:

Slowly and stumblingly, ascending the stairs, supported by Grimsby and Hattersley, who neither of them walked quite steadily themselves, but were both laughing and joking at him, and making noise enough for all the servants to hear. He himself was no longer laughing now, but sick and stupid – I will write no more about that.

Helen has come to feel helpless to prevent her husband’s drinking. The realisation that he cannot be (and does not want to be) saved resonates with Anne’s despair of a cure for Branwell. Far from “trembling day and night”, as George Eliot pictures them, the sisters transformed their experiences into some of the most powerfully dark and didactic fiction of the 19th century.