Welcome to the second part of Breaking Nations, a series of articles that examines independence movements across the globe ahead of the Scottish referendum in September. For this edition, Francois Gelineau reports on this week’s general election in Quebec.

The Québec separatist movement suffered an almighty blow on Monday. After just 18 months of minority government, the Parti Québécois (PQ), the standard bearer of the movement, prematurely led Quebecers into an election. The party lost almost half of the seats it held in the legislature, losing the election as a result.

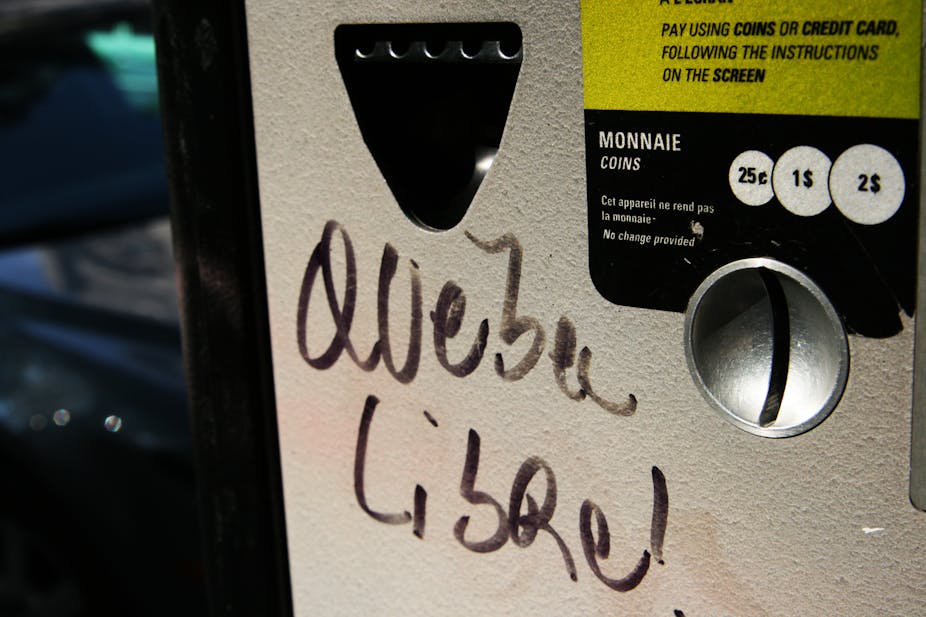

The separatist movement has been at the forefront of Québec politics ever since the 1970s. The province has held two referendums on independence, one in 1980 and the other in 1995.

The separatists lost both, the latter by less than two percentage points. Since 1995, not unlike Scotland, support for Québec separation has oscillated between 35 and 40%. These numbers had not changed in the run-up to this week’s election.

Whose idea was an early election?

When the PQ government announced an early election on March 5th, it was emboldened by favourable poll ratings for the administration. In so doing, it acted against the principles of the fixed election bill that it adopted in the first months of its short existence.

Yet during its 18-month tenure, the PQ Government prepared the way with an active legislative agenda. Among other things its bill proposals included improved government ethics, cleaner political party financing, and a controversial secular charter.

And on the eve of the campaign, the PQ had a clear lead in the polls. Many analysts were even suggesting the possibility of a majority government.

The following 33 days were an unprecedented political roller coaster ride. Two weeks in, the question of Québec sovereignty began to enter the debate. Whether or not this was to blame, what followed was disastrous for the party.

Vive le Canada!

New public opinion surveys started to suggest a downward trend for the PQ. By the end of the campaign the Liberal Party (PLQ) had clearly taken pole position, leaving the PQ almost 15 points behind.

Most analysts agree that the 2014 election has been the most divisive and acrimonious in recent history. It has mainly revolved around personal attacks, not policy proposals. Along with changing patterns of voter preference and the increased numbers of political parties, this negative tone may well have contributed to the result.

The PLQ has undeniably regained the support of many Quebecers only 19 months after being brutally ejected from a 10-year stint in government. The party will now have a clear majority in the National Assembly for the next four years.

But more importantly, the results represent a bad PQ defeat. The party finished second, only about two percentage points above the centre-right Coalition Avenir Quebec (CAQ). Québec premier and PQ party leader Pauline Marois also lost her seat, and stepped down from her party post immediately.

It is hard to say to what extent Québec separatism contributed to the PQ loss, but the consequences for the separatist movement and especially for the party are clearly detrimental. These results will force a period of introspection.

The party will need to revise its strategy on secularism. The tone of the debate has clearly provoked a growing sense of “us versus them” among Quebecers. The divide between those that feel they are part of “us” and those that associated with “them” has been harmful.

Young Quebecers spurn separatism

One major shift in public opinion is also worth mentioning. Québec separatism used to be especially popular among young and more educated voters, but no longer.

Newer voters are seemingly more interested in other issues that were mostly absent from public debates during this electoral campaign. Education, the environment and intergenerational equity are good examples.

Recent survey data suggest that separatism is now most popular among voters aged 55 and over. This is not surprising in some ways, since those voters instigated the separatist movement in the 1970s.

Whether the Quebec sovereignty question is dead or alive is open to debate. One thing is clear however: the province’s politics are changing. The PQ clearly needs to adapt to the new reality if it wants to regain the lost ground.

To read the other instalments of our Breaking Nations series, follow the links below:

Part One: Catalonia deadlocked as nationalists plan new offensive