Long after President Obama’s re-election was secure, another election day result came in, one that may be of comparable significance in the long run.

By a 54-46 margin, Californian voters approved Proposition 30, which raises about $6 billion a year in additional income and sales taxes to prevent further cuts in education spending.

To appreciate the historic significance of this measure, it’s necessary to go back to 1978 and the passage of Proposition 13, which slashed property taxes, and imposed high barriers to any future increase in taxes.

Proposition 13 heralded the beginning of a global “Tax Revolt”, and the end of a century-long trend towards an increase in the share of national income allocated to public services.

In this country, the campaign was taken up by The Australian and had its echoes in the “Joh for Canberra” campaign a decade later, based on a 25% flat tax. More seriously, the Hawke government adopted the Trilogy commitment, promising not to increase the ratio of public expenditure or taxation of national income. Although the commitment was temporary, the constraint has proved durable in practice.

The government revenue share of GDP was 24% in 1984, when the commitment was made, and it has remained at that level, plus or minus a couple of percentage points, ever since.

More broadly, the Tax Revolt signalled the end of the postwar era, in which the social democratic welfare state provided security against the risks of unemployment, illness and poverty, and the rise of market liberalism (commonly, though misleadingly, called ‘economic rationalism’ in Australia).

The rich got much richer, while the poor and middle classes did as best they could - in the US, not very well at all. In California, Proposition 13 produced a slow-motion fiscal crisis, as a succession of governors struggled to reconcile rising expenditure needs and stagnant revenues. The problems were exacerbated by the “three strikes” law of 1994, also passed by referendum, which packed the state’s prisons.

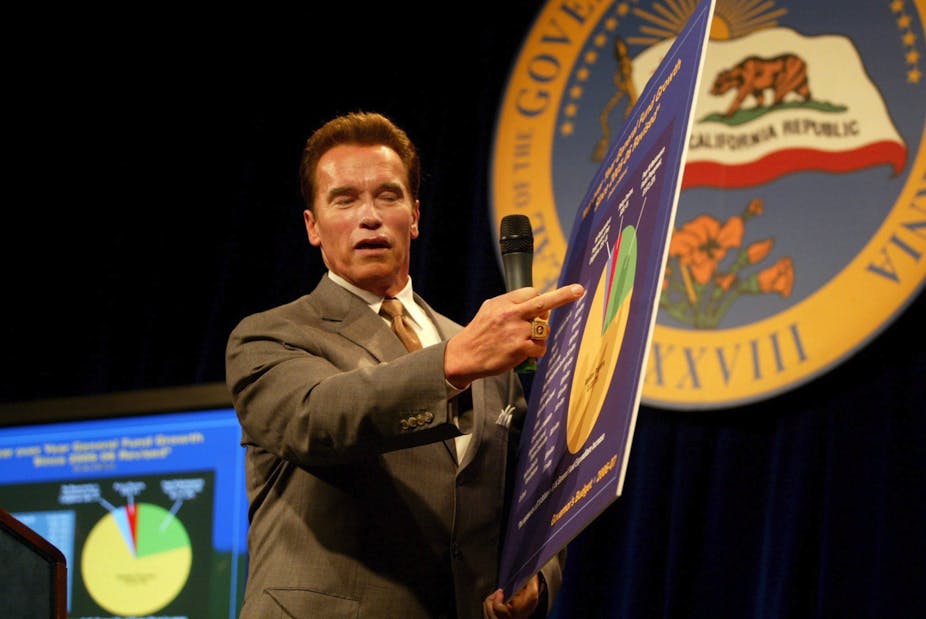

By 2012, California was spending more on prisons than on higher education. With the exception of prisons, services were cut repeatedly, but never enough to balance the books. In 2009, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger was reduced to issuing IOUs to pay the state’s bills.

A series of desperate expedients eventually staved off bankruptcy, but it was obvious something had to give. The pressure was sharpest in education. In 1960, California’s Master Plan for Education gave it easily the best public education system anywhere in the world.

The University of California system, with campuses such as Berkeley and UCLA attracts most attention, but the network of state universities and community colleges served a much larger section of the population and was also excellent, as were the public elementary and secondary schools. It takes a long time to erode that kind of advantage, but decades of financial stringency have done so quite effectively.

The cuts needed to balance the budget in 2013 would have been a death blow. Any plausible solution required more tax revenue, but Proposition 13 required a two thirds super majority in the state’s Assembly and Senate to pass such a change. The Republican party, although in a permanent minority, resolutely blocked all measures of this kind. As a result, Governor Jerry Brown was forced to go to the public with a referendum to increase taxes. That’s obviously a difficult question to push, even when the need is clear.

But, finally, Californians showed they had had enough of the failed ideas of the late 20th century. Not only did they approve the tax increase, they elected a Democratic supermajority. And, in a triple win for rational policy, they relaxed the three-strikes law, making it impossible for someone to be sentenced to a 25 year-to-life term for trivial offences like petty theft.

What does this mean for Australia?

It has becoming increasingly obvious that Australian governments cannot meet their basic commitments to provide health, education and welfare services while remaining within current budget constraints. The problem is only going to get worse if the problems in school funding identified by the Gonski review are to be addressed and if initiatives like the National Disability Insurance Scheme and publicly funded parental leave are to proceed.

The Global Financial Crisis signified the failure of the free-market policies for which Proposition 13 was the harbinger. It’s time to recognise, once again, that we can never be truly prosperous without high quality public services and that the only way to pay for those services is through taxation. California has learnt this lesson the hard way. Australia can surely do better.