International Women’s Day has just passed, and, as always, there was little if no mention of Canada’s suffragists.

This May 24 marks the centennial of the federal act to give women the right to vote. Despite the fact that most Indigenous and some Asian women were excluded for decades, no other single piece of legislation enfranchised so large a proportion of Canadians.

Doubling the electorate was one clear step on the long road to full democracy.

But commemoration of that federal milestone, like that of its provincial counterparts beginning in 1916, is curiously low-key in Canada, especially in comparison with how it’s celebrated in New Zealand, Australia and the United Kingdom.

In the context of today’s urgent preoccupation with the democratic deficit — from low voter turnout to pervasive alienation from electoral politics — and enduring gender inequalities in wages and representation, Ottawa’s neglect, especially with a self-proclaimed feminist prime minister in office, demands explanation.

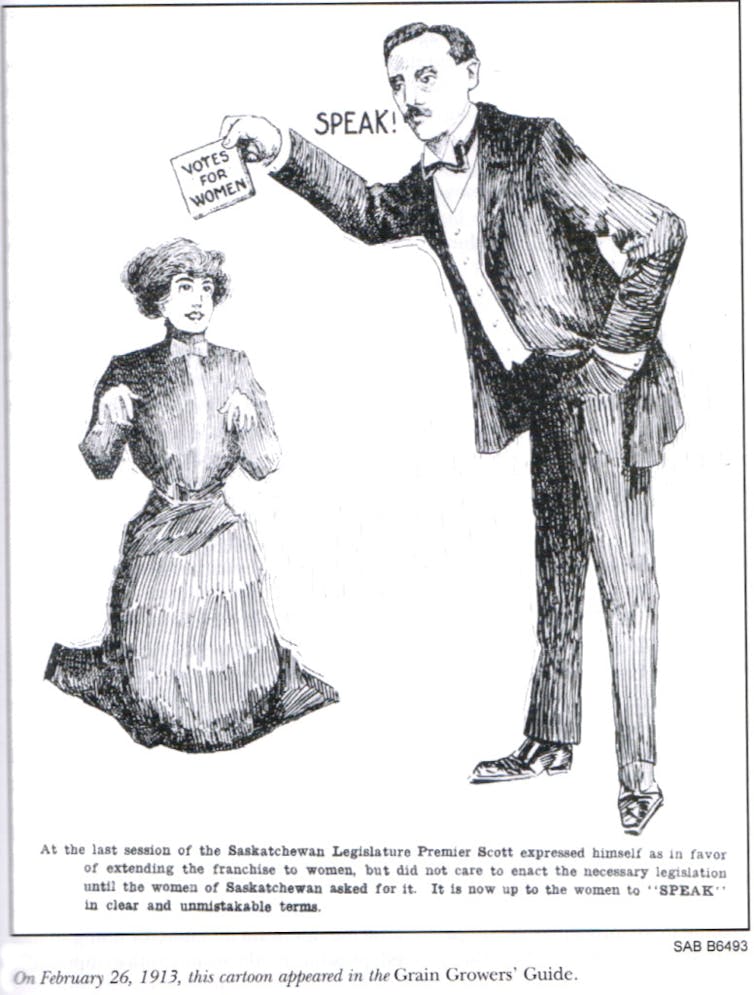

Part of the story lies with the misogyny and misunderstanding dogging conventional accounts of Canadian suffrage.

Suffragists have faced a century and more of popular and scholarly caricature and inattention. Women’s roles in forging Canada’s democracy have gone largely missing in official accounts of Canadian history.

Forgetting the suffragists’ bold battles for equality is not, however, the sole cause of today’s commemorative shortfall. The politics of remembrance has become a contemporary minefield.

Flawed historical figures from John A. Macdonald, recently condemned for his advocacy of the residential school system for Indigenous children, to Nellie McClung, maligned for her racism and support of eugenics, are grabbing the historical spotlight as today’s Canadians attempt to address historic and institutional injustices.

Challengers of racial prejudice like E. Pauline Johnson, a Mohawk-English writer and performer who railed against the “might makes right” approach in Canada’s treatment of Indigenous peoples, and Black Nova Scotian activist Viola Desmond, who demanded civil rights and whose face now appears on Canada’s $10 bills, correctly call for overdue respect.

In this heated climate, mainstream suffragists who pushed for women’s right to vote are risky subjects for nervous politicians.

Neglecting the recognition of the great strides made by suffragists, however, is no antidote for the ills of inequality that have plagued Canada. History has lessons to teach.

This year, UBC Press has launched its warts-and-all seven-volume series Women Suffrage and the Struggle for Democracy in Canada. The first volume, by Trent University historian and women’s studies professor Joan Sangster, is entitled One Hundred Years of Struggle: The History of Women and the Vote in Canada. It reminds us why suffrage continues to matter.

Advanced equality

Even as prejudices of race and class affected their vision, suffragists advanced equality and raised issues that remain with us today — from violence against women and girls to the value of unpaid labour.

What’s more, the UBC Press series properly rescues from obscurity the anti-suffragists’ endorsement of an ultimately brutal regime of male — and class and race — privilege in families, education, the economy and politics, which continues to threaten democracy to this day.

Suffragists did not take Canada all the way to the “land of the fair deal” glimpsed by McClung. But unlike the timid, the ignorant, and the reactionary — sometimes a majority, then as now — they spied that destination. The flawed beliefs of some of them should not blind us to the courage required to win the vote for most women, and to contest barriers to equality for all in general.

Today, just as when women won the vote, democracy remains a work in progress, its allies imperfect, its opponents many.

In 2018, official commemoration of women suffrage needs to tell that evolving democratic story. To do otherwise denies Canadians’ capacity for change.