Goths, punks and hipsters roam the streets, wilfully asserting their counter-cultures. But in an age of cultural appropriation, is this resistance just another way of fitting in?

In 2015 can anyone truly embrace the bohemian spirit of freedom and rebellion? Particularly in Australian culture – who or what is a bohemian?

Monash academic Tony Moore wrote an excellent book on the topic, Dancing with Empty Pockets: Australia’s Bohemians in 2012. Now the State Library of Victoria is staging a provocative exhibition, Bohemian Melbourne, examining Melbourne bohemians from the 1860s through to the present.

Bohemian rhapsody

The concept of “the bohemian” is impossible to define. Authors Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley in London and Marcus Clarke in Melbourne are thought of as archetypal bohemians of the 19th century. Subsequently, so too were the punk rockers of the 1970s and 1980s, avant-garde artists, street and graffiti artists, cabaret performers and frankly anyone else who identified with any of the numerous counter-cultures.

In some ways it is easier to define those who are not the bohemians - the official establishment. However, even an exclusive Melbourne men’s club, the Savage Club, has members who I suspect would consider themselves bohemians.

The name itself is a misinterpretation of a misnomer. In France “bohemians” was a name applied to gypsies, who were mistakenly thought to have come from Bohemia. This was subsequently extended to describe the artistic fringe, whose members were impoverished and who were frequently itinerant and moved around like gypsies.

French novellist Henri Murger’s collection of stories, The Bohemians of the Latin Quarter (1845), to some extent codified the experience and Italian composer Giacomo Puccini appropriated parts of it for his opera La Bohème.

To be a bohemian is to adopt a state of mind and to seek a truth or a lifestyle which may not be commonly accepted.

The curator of this exhibition, Clare Williamson, adopts this broad-church approach to the idea of a bohemian in Melbourne and presents a fascinating cross-section of bohemians, as individuals and in clusters, clubs, cabarets and enclaves, over the past 150 years.

Bohemian culture in marvellous Melbourne

Marvellous Melbourne, which arose out of the egalitarianism of the gold rushes, gave birth to a strong bohemian culture. Marcus Clarke, the London-born journalist, writer, librarian and professional bohemian, joined the Athenaeum Club and founded in 1868 the Yorrick Club, Australia’s first bohemian club, which became a magnet for men of letters.

He was a dressed-up dandy, a flâneur and a heavy drinker, but had a touch of genius with his novel, For the Term of His Natural Life (1874/75), one of the classics of Australian colonial literature. He was dead by the age of 35, with suicide rumoured but rejected by his actress wife, Marian Dunn, the mother of his six children. Clarke in his behaviour and creative achievement became a model for other Australian bohemians to follow.

Artists’ camps in the closing decades of the 19th century, some associated with the so-called Heidelberg School and including Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Charles Conder and Frederick McCubbin, were one possible expression of Melbourne bohemianism.

The golden age of Melbourne bohemians arose from the Great Depression and the second world war and was clustered around several distinct geographic locations on the outskirts of Melbourne and several watering holes in Melbourne itself.

Heide, built around the bourgeois patrons, John and Sunday Reed, attracted Sidney Nolan, Bert Tucker and Joy Hester. In Warryndyte, Danila Vassilieff created his own bohemian centre built around Stonygrad.

At Murrumbeena, at Open Country, Arthur Boyd and the rest of the Boyds, joined by John Perceval and intellectuals Peter Herbst and Max Nicholson, created another bohemian hub. As did Clem and Nina Christesen at Eltham at Stanhope, with the important literary journal Meanjin Papers at its centre.

Down the road was the artists’ colony of Montsalvat, with Justus Jorgensen at the helm, while a few kilometres away was Clifton Pugh’s artists’ colony named Dunmoochin at Cottles Bridge. In Melbourne itself, bohemian artists and intellectuals met at the Swanston Family pub, the Café Petrushka, the Mitre Tavern and subsequently at the Mirka Mora café.

Clare Williamson in her intriguing exhibition brings together a richly contextualised account of Melbourne bohemia documented through paintings, manuscripts, artifacts and photographs.

Capturing the bohemian spirit

For a phenomenon that is as transient as smoke, as difficult to grasp as liquid mercury and as faction-ridden and self-contradictory as a right-wing political splinter group, this is a remarkably coherent account of Melbourne bohemianism.

In the 1950s and 1960s, with the advent of outrageously bohemian characters such as the dancer Vali Myers and the comedian Barry Humphries, a certain sense of structure appeared in the Melbourne bohemian fold and the establishment started to anticipate and enjoy the bohemians and their antics.

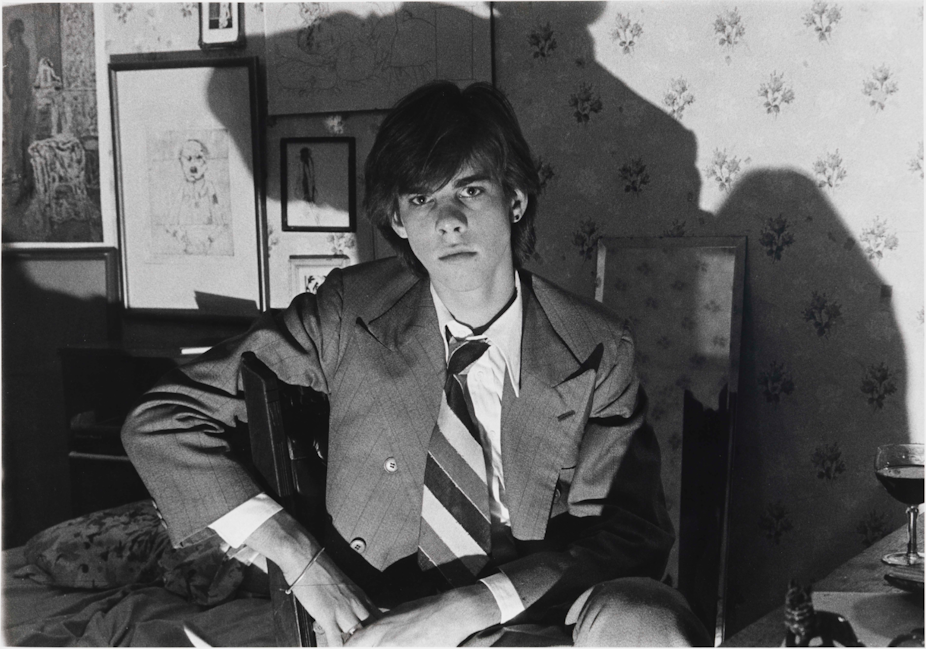

The mass movements of the 1960s and ‘70s, sexual liberation, performance poets and the punk bands all blurred boundaries as forms of bohemian behaviour merged with youth counter-culture and Nick Cave and Paul Kelly started to nurture an audience and reap economic returns.

One could question whether the concept of “bohemian” has become so mainstream today as to annul the earlier usefulness of the term. What this exhibition does achieve is to successfully document the rebellious spirit in Melbourne cultural life with some of its glorious successes and moments of infamy and humour.

Bohemian Melbourne: Artist, rebel, hippie, hipster? is showing at the State Library of Victoria until February 22. Details here.