Earlier this year, I stayed at the Blackman Hotel in Melbourne where I spent the night gazing at a painting of a shrinking Alice glowing on the wall opposite.

In Charles Blackman’s painting - from his Alice in Wonderland series - she is seated at a table in a huge chair that threatens to engulf her. Several huge objects on the table are toppling disturbingly.

Hovering on a tabletop that is dissolving before our eyes are cups and a teapot, with a small, white rabbit hanging magically suspended in the miasmic grey space of the picture. In the bottom left-hand corner, an open trap door provides hope of escape.

This painting enthralled me during my waking hours. The idea of a hotel devoted to the work of an artist had seemed somewhat twee before I stayed in one. Yet afterwards, I was convinced by the notion - and grateful to have had the chance to share my evening with Blackman’s vision.

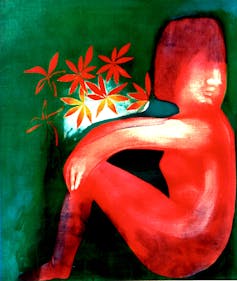

Blackman, who has died aged 90, had a contagious, childlike wonder in engaging with the world. His many series of paintings depicting children, schoolgirls and, of course, Alice in Wonderland are a testament to his ability to embrace the joy of discovery evident in children’s drawings.

It’s not surprising that in the 70s, Blackman was involved in documenting the work of untrained, so-called “primitive” artists. Working with Geoffrey Lehmann on his Australian Primitive Painters he championed the works of Henri Bastin, Charles Callins, James Fardoulys, Sam Byrne and Irvine Homer. All great image makers with a vision that is fresh and unmediated.

For Blackman, the narrative urgency evident in these artists’ work, their need to tell their story using whatever means were available, was an inspiration. However, to coin a phrase used by Edward Mullins in his monograph on the great English artist Alfred Wallis, that compulsion to tell a story was combined with natural sophistication: an ability to make work that while not adopting the traditional modes of picture making, shows a deep understanding of the principles of orchestrating space within the plane.

Mostly self-taught, though he did attend a few night classes at East Sydney Technical College between 1942-45, Blackman travelled to Melbourne in the early 1950s where he found support and encouragement from the artists he met through John and Sunday Reid at Heide. Robert Dickerson, Arthur Boyd, John Perceval, Joy Hester and Danila Vasilieff were also storytellers interested in the vibrancy and freshness of children’s art.

Imbued with these ideas and buoyed by the earlier success of his Schoolgirl series, Blackman was introduced to a recording of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland by his wife Barbara in 1956.

Read more: The schoolgirls of Charles Blackman – haunting works from a politically innocent age

Due to her failing eyesight, she didn’t have a copy of the book with the famous John Tenniel illustrations. So Blackman was able to discover his image of Carroll’s cohort of extraordinary characters by going inside himself.

Those images were then placed in an expansive field that opens up our imagination as viewers to enter and move around freely. It is what gives the series their poetry and also their poignancy.

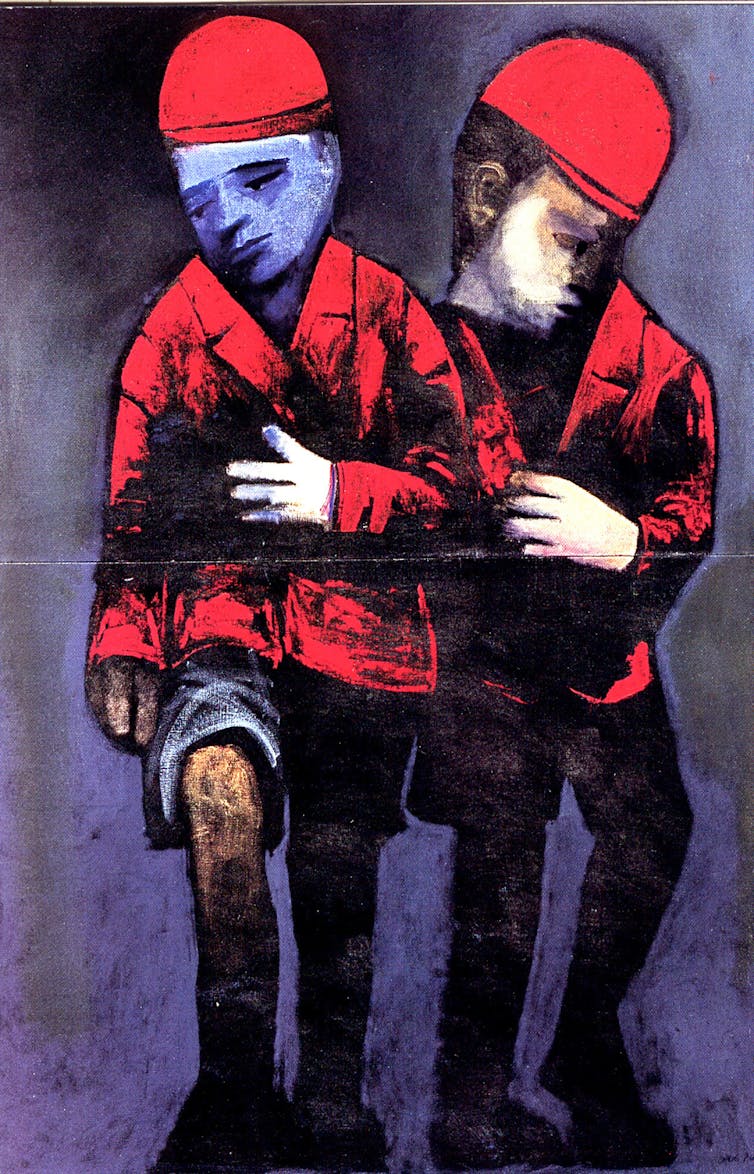

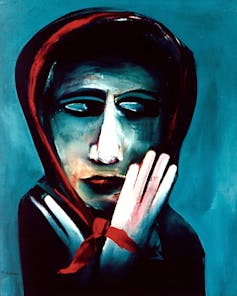

While based in London in the 1960s, Blackman sent back exhibitions to Australia, including one to the Skinner Galleries in Perth, with images of women with closed eyes holding bunches of flowers; silhouetted figures standing in groups, their heads turned away and dark faces enclosed in multiple window panels.

They were haunting and deeply personal responses to his wife’s blindness. Blackman’s paintings demanded attention because they were stories that needed to be told. But they also engaged the viewer by subverting the conventions of picture making. Like Henri Bastin, James Fardoulys and Sam Byrne, he created space in his paintings that created the ambience within which to read them. The Alice pictures are open and slippery; the London paintings tight and locked in. We feel the emotional intent.

When the National Gallery of Victoria presented Felicity St John Moore’s retrospective of Blackman’s work, Schoolgirls and Angels, in 1993, and celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Alice in Wonderland paintings in 2006, it was an opportunity to reflect on his formidable contribution to image making in Australia.

Blackman forged an urbanised image of Australia that for most, was more familiar than the mythic landscapes of Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd, and Russell Drysdale. It may be familiar but it remains uncomfortable. For underlying his poetic vision is an undertone of dread, the low rumble of imminent mortality.