In the summer of 1967, three of the four cardiac surgeons competing to perform the first human heart transplant were simultaneously just hours from their place in the history books. But each was thwarted – none of the planned operations went ahead. All four would come close again. But the race was finally only settled on December 3, 1967. Like that other iconic moment of the late 1960s, man’s small step onto the moon, the first human heart transplant was a giant leap that would be felt around the world.

The South African doctor Christiaan Barnard was spoken of in the same breath as Neil Armstrong after he abruptly became a worldwide celebrity on December 3, 1967. His patient, 55-year-old Louis Washkansky, was also catapulted into the spotlight for the 18 tumultuous days he lived after receiving a new heart in Cape Town from 25-year-old traffic accident victim Denise Darvall.

A gifted surgeon and trailblazer from a resource poor country, Barnard was nevertheless a peripheral character in the field of cardiac transplantation research. Years of meticulous work and animal experimentation by Americans Norm Shumway, Richard Lower and Adrian Kantrowitz meant that by 1967 the quest to be first was no less exciting than the space race. None of them expected a man with no background in cardiac transplantation research to leapfrog them, but Barnard’s imperious self-confidence would surprise everyone.

Primate hearts

There had been a false start in 1964 when American surgeon James Hardy turned to desperate measures in an attempt to save a patient’s life. He was aware that a man had recently been kept alive with a circus chimp’s kidney. As a result, Hardy had purchased four chimps and decided to transplant one of their hearts into his patient. It was a disaster. The man died on the table and the public backlash was fierce. Hardy never attempted another heart transplant.

Over the next few years, the world eagerly waited for one of the three American doctors vying for success to write their name into history. But history had other ideas, as Barnard, who had learnt much while observing Shumway and Lower, beat Kantrowitz by a matter of days.

But as mentioned, his patient, Louis Washkansky, died of a chest infection 18 days later. Barnard, perhaps ill-advisedly, revealed his quintessentially surgical mindset when he announced that despite the patient’s death, his operation had been a success, as the postmortem revealed a “beautiful heart”.

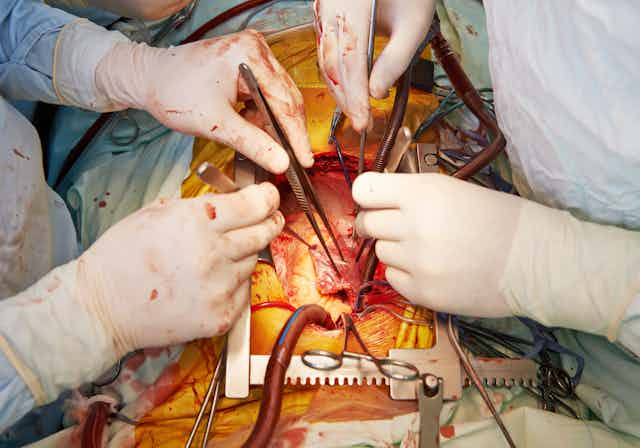

This was a pattern that would repeat itself across the world as heart transplantation took off like wildfire. But suturing in a heart was the easy bit; it would be two decades until we understood and could effectively treat rejection.

After initial excitement, the realisation that most patients lived weeks or months meant practically everyone abandoned it. In 1968, there were 100 heart transplants performed worldwide; in 1970, just 18. Norm Shumway almost single-handedly kept the idea alive and hence is remembered as the father of heart transplantation, even if it was Barnard lauded on the front cover of TIME Magazine, or partying with Sophia Loren on the inside pages.

Ethical dilemmas

The jubilant atmosphere surrounding Washkansky’s transplant happened against the backdrop of apartheid South Africa. A country shunned by much of the world rejoiced at their opportunity to show they were a modern nation. But the spectre of race had clouded the ethical issues surrounding transplant in both South Africa and 1960s America.

Barnard’s hospital had secretly decided to avoid a transplant operation involving a black recipient, lest they be accused of experimenting on a subjugated minority. One month prior to his transplant, Washkansky, a white immigrant from Lithuania, was moments from receiving the heart of a black man, but ultimately a medical reason gave the hospital a welcome excuse to cancel the procedure. Denise Darvall was also white and so while the gift of her heart was celebrated around the world, her kidneys were more controversial as they were donated to a mixed race 10-year-old boy.

The other major ethical and theological topic of discussion concerned how to appropriately retrieve organs from a donor. Patients with a fatal head injury may have irreparable brain damage but their heart will continue to beat, a concept known as brain death. This represents the best chance for successful transplantation as organs stay viable as long as the heart is beating. Once the heart stops beating and circulatory death occurs, organs begin to get damaged, especially the heart itself.

Brain death was not legally recognised in 1967 – death was then defined by American law as the lack of a heartbeat. Shumway was critical of this archaic “boy Scout definition” of death. It meant doctors would have to wait for the donor’s heart to spontaneously stop beating. South Africa’s looser legal definition of death benefited Barnard, who simply needed the approval of the state’s forensic pathologist, in contrast to staunch initial opposition to recognising brain death in the US.

The perils of operating in this new frontier were made all too apparent when Japanese surgeon Juro Wada performed his country’s first heart transplant. His donor was what today would be recognised as brain dead but Wada was charged with murder and waited several years to be exonerated. Japan didn’t perform another heart transplant until 1999.

Heart legacies

And what about the legacy of xenotransplantation – organ donation across species? This had kept a low profile since the catastrophic 1964 attempt to transplant a chimp’s heart. But in 1984, the American surgeon Leonard Bailey controversially selected a baboon’s heart in an attempt to save a two-week-old girl who became known as Baby Fae. She lived for three weeks. Allegations later surfaced that Bailey rejected an available human donor and exaggerated chances of success on the consent form.

The heart transplant was the 20th century’s landmark medical event. In the UK, there are six heart transplant centres, the largest of which is Papworth Hospital in Cambridge, where I received my training. The first recipient of a successful heart transplant in the UK had their operation at Papworth. Another Papworth patient is approaching the 35th anniversary of their transplant, thought to be one of the longest surviving heart transplant patients in the world. Papworth has recently pioneered a new way to perform transplants, so that donors who have suffered circulatory death are now also suitable. This means the number of potential donors will soon increase considerably.

Tens of thousands of lives have been saved since Denise Darvall’s posthumous act of generosity and heart transplantation has grown to comprise about 5,000 operations around the world each year. Yet in 2016, 457 people died awaiting organ transplant in the UK. The operation itself has only been modified slightly since 1967 and despite our best attempts to build a replacement heart, the gift of organ donation remains many people’s best hope for life.