When it comes to great names in French anthropology, many people know of Claude Lévi-Strauss, who passed away in 2009 at the age of 100. Others might cite Lévi-Strauss’s late colleague Germaine Tillion or Françoise Héritier, whose work on gender has marked generations of young researchers worldwide.

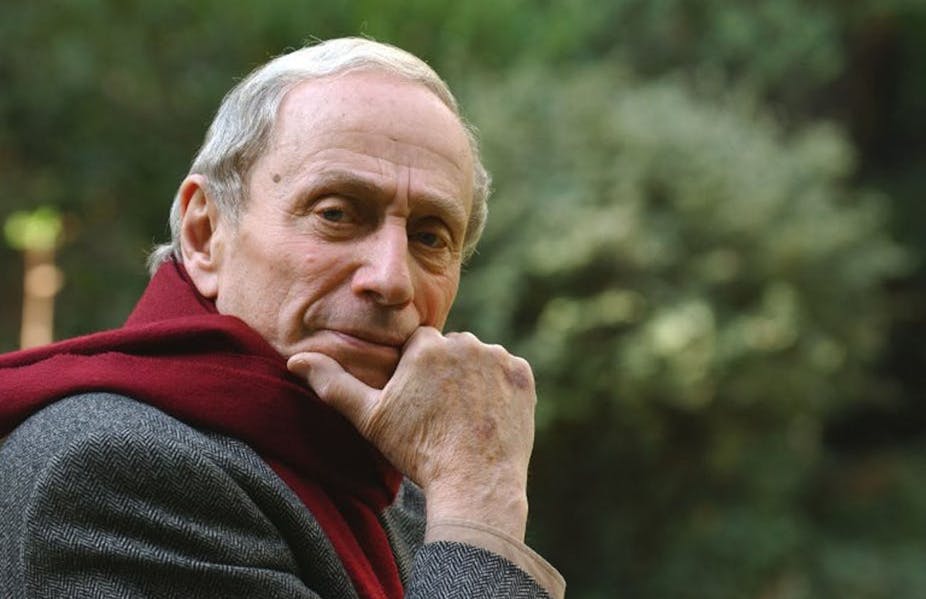

Few would immediately think of Georges Balandier, who passed away in October 2016. Yet Balandier was an eminent specialist in African studies, and left his mark on the history of anthropology.

Understanding change

Unlike Claude Lévi-Strauss, Balandier’s ambition was not to reshape the aims and methods of anthropology. Instead, he saw anthropology as the study of man in modern times. Rather than looking for consistency and parallels, he was more concerned with contingency, indeterminacy, disorder and events. Notions of invariance, structure and homology were entirely foreign to his way of thinking.

For Balandier, anthropology was first and foremost the analysis of situations – specific states of society, inseparable from their shifting power dynamics, or struggles over meaning. If we assume that instability is the normal state of human collectives, we cannot expect to find durable structures underpinning them.

Balandier’s anthropology was therefore a “dynamic anthropology”, an approach that bears a surprising resemblance to the sociology of Pierre Bourdieu. Bourdieu explicitly identified with the structuralist tradition and emphasized the notion of “field” – a social structure that determines individual behaviour – and both men worked the space between sociology and anthropology. Each held as essential the notion that social struggles are also struggles for meaning and, in effect, the definition of social reality.

An inverted vision of the world

As early as 1953, Balandier demonstrated how the struggle against colonialism was associated with an inverted vision of the world: according to religious vocabulary, colonised Africans were the chosen people of a God who spoke through their prophets. From this, Balandier derived the idea that anti-colonialism was expressed through messianic movements that completely reframed the situation of domination.

Even today, movements like Bundu dia Kongo (literally “Gathering of Kongo”) in the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire) are both political and religious. Ne Muanda Nsemi, the movement’s leader, is both a messianic figure and warlord, fighting to overthrow the territorial divisions of colonization and re-establish the borders of the 15th-century Kongo empire.

It is worth noting that Bourdieu explicitly used the concept of the “colonial situation” – a term Balandier coined in 1951 – in his first book in 1960. In Sociologie de l’Algérie, Bourdieu wrote:

“It is important to understand the lifestyle and value system of Europeans in the framework of the colonial situation, and their relationship to colonised peoples.”

Some categories used by the young Bourdieu – “dynamic equilibrium”, “cultural interpenetration”, “partial re-interpretation” – are related both to Balandier’s vision of sociology and to the work of Roger Bastide, one of the greatest experts on Brazilian culture, whose theories were close to Balandier’s.

A tribute to Balandier in Cahiers d’études africaines, a review of African ethology which he helped found, gives a clear insight into his innovative cross-disciplinary analyses and his influence on both the social sciences and humanities.

While his work belongs to the specific field of political anthropology and is structured around the concept of power, it is above all an invitation to examine our ever-changing societies and cultures in a far-reaching and exhaustive manner, touching on religion, rituals and the sacred, the economy and work, as well as kinship and gender.

Opening up a dialogue between ‘order’ and ‘disorder’

His early work on the Congolese city of Brazzaville and the “colonial situation”, in particular Sociologie actuelle de l’Afrique Noire (1955), broke with the anthropological tradition. It challenged the culturalist, formalist and materialist schools of thought developing in the wake of World War II, and instead focused on folklore and myths. Balandier distinguished himself not only from structuralism and Marxism but also from a large section of British and North American anthropology that, while dealing with cultural change (acculturation), failed to connect it to the social frameworks in which it occurs.

In this context, Balandier’s approach was highly original. He developed a broad, comparative brand of anthropology, aimed at understanding and capturing the historical dynamics shaping social and cultural phenomena. His focus on dynamics revitalised the epistemological basis of anthropology. By investigating the relationship between “tradition” and “modernity”, and creating dialectics between order and disorder, he challenged the ahistorical work of his predecessors.

Another perspective on kinship

For Balandier, kinship is an extremely important concept. His analyses on the subject, while only a small part of his prolific body of work, demonstrate the evolution of his definition of power. To him, kinship constitutes a secondary object of study when compared to the place it occupies in classical anthropology and the work of Lévi-Strauss.

Initially, Balandier defined kinship as a relation of dominance, reshaped historically by the intrusion of a foreign power, then as a model for “mutation” elucidating the internal and external origins of change. But while the “imaginary” and the “symbolic” enable us to identify power dynamics within family bonds, kinship is nonetheless determined by geography, as Balandier brilliantly demonstrated in his work Sociologie des Brazzavilles noires. At its core, dynamic anthropology offers a vision of politics that linked power, space and the symbolic.

From possession to power

It is possible that Balandier’s direct experience of possession and divination rituals in Africa may have sparked his particular fascination for religion, beyond the sociology of religious institutions. He was struck by the emotions these rituals elicited, as was Michel Leiris, writer, poet and author of L’Afrique fantôme (1934).

These physical, subjective, existential ordeals enable a better understanding of the dynamics of domination and resistance. This explains why Balandier focused on the political role of religious movements in the context of decolonisation and, ultimately, on the volatile nature of the sacred within “hypermodernity” when it appears outside of religious institutions.

Balandier’s anthropology was one that engages the anthropologist above and beyond the purely logical analysis of structuralism. A dynamic anthropologist is also an engaged anthropologist, not politically, but existentially: the subjective engagement of researchers in their field guides their analyses as much as the data they collect.

Since all societies and all cultures are subject to contingencies and “turbulence”, anthropologists must describe the ambiguities and contradictions that destabilise the social and cultural order. “Tension”, “conflict”, “events” and “situations” constitute a methodological frame of reference that Balandier was able to apply beyond the limits of academic disciplines. In today’s postmodern times, a cross-disciplinarily approach is vital to understanding the changing dynamics of power, society and culture.

The authors of this article recently published “L’anthropologie de Georges Balandier, hier et aujourd’hui” (The anthropology of Georges Balandier, yesterday and today), a special dossier in the latest edition of cArgo magazine.

Translated from the French by Alice Heathwood for Fast for Word.