One of the few bits of political memorabilia I own is a copy of the parliamentary proceedings – the Hansard – of Tuesday, March 18, 2003, signed for me by the then chief whip, Hilary Armstrong. That day we witnessed the largest backbench rebellion by government MPs of any party, on any subject, since modern British politics began. That day a total of 139 Labour MPs voted against their party’s whip, and against the Iraq war.

Last night’s votes on Syria saw a smaller government rebellion – early reports indicate about 40 Coalition MPs voted against their whip – but in its own way it was just as significant.

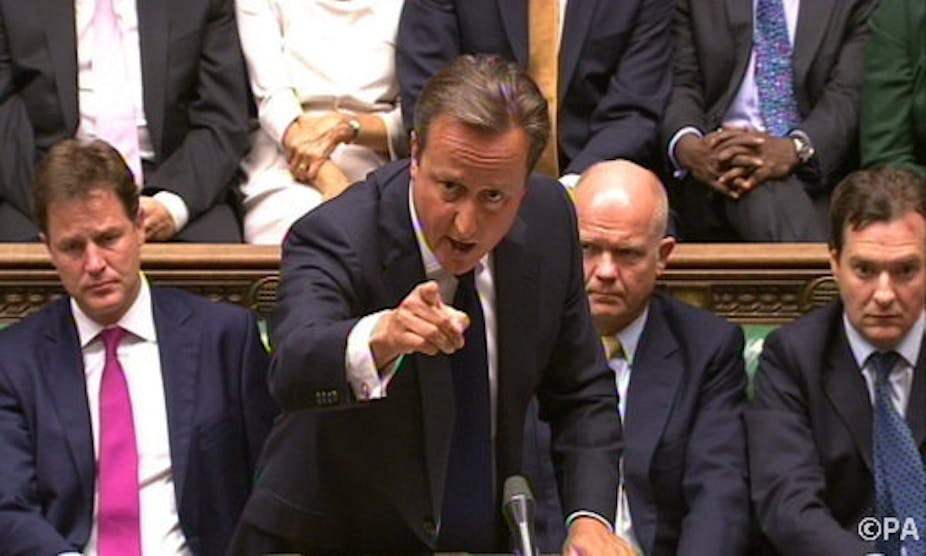

Explaining the outcome is – when you cut through the guff – relatively easy. Two factors came together. One crucial difference between Iraq and Syria - and between Syria and every other vote on military action since Suez in 1956 - is that those votes all saw the Labour frontbench support the government, whereas last night Labour voted against the government, on both their amendment (which was easily defeated by 332 votes to 220) and the government’s motion (more narrowly defeated by 272 votes to 285).

In 2003, Iain Duncan Smith led Conservative MPs into the same division lobby as Tony Blair in support of military action in Iraq. As a result, almost no matter how large the Labour rebellion, the government was bound to win.

That the government could not rely on Labour support last night is one reason why the outcome of the votes was so uncertain. And it is one of the reasons they lost the second one. But Labour’s votes are only half of the explanation. The other half is the scale of backbench rebellion on the government side. This is a government with a de facto majority of around 80; even without opposition support it should not be in this position. Its difficulties over Syria are emphatically not a result of being a coalition.

While there was some opposition from within the Lib Dems, this was not an occasion like the vote over parliamentary boundaries, where the Liberal Democrats defected en masse. The government’s problems were as much with Conservative backbench opponents of intervention. There were said to be at least 80 Conservatives with serious doubts about the idea of intervening in Syria; at least 30 of those voted against the government, others abstained.

Tory backbench flexing its muscles

This is just the latest piece of evidence of the steady rise of backbench independence, which I’ve been tracking over the last decade or more. This did not begin in 2010 – there were plenty of signs of it in both the 2001 and 2005 parliaments – but there has been a further step change up in the levels of independence being displayed by MPs since the last election. This is a parliament that has seen MPs vote to amend their own government’s Queen’s Speech, something that had previously been unprecedented. Now they are willing to do the same to its foreign policy. This is parliamentary influence, for good or ill.

Iraq aside, most recent rebellions over military foreign policy, especially on the government side, had been small. Rebellions on the Iraq bombing of 1998 were minor, involving just 22 Government MPs. The same applied to the vote over the bombing of Kosovo in 1999 which involved 13 and Afghanistan in 2001. The same was true of rebellions in this Parliament until last night. Over Iran, Libya and Afghanistan; none had involved more than five coalition MPs. There were some half-decent-sized rebellions amongst Opposition MPs against the first Iraq war in 1990-91, but not amongst government MPs. Iraq was very much the exception – until last night.

Contrary to myth, governments do lose votes in the Commons occasionally without resigning or resorting to votes of confidence. They even occasionally lose them over foreign policy – at least broadly defined. But no government has lost a vote over matters of defence or military involvement since at least the mid-19th century. The fact that the only comparable votes involve Lord Palmerston, Lord Aberdeen and even Lord North is a sign of how far back in time you have to search.