At different times ahead of the 2014 Commonwealth Games, various politicians called for politics to be kept out of the event. This didn’t prevent the organisers paying tribute to Glasgow’s part in the Free Mandela movement in the 1980s at the opening ceremony.

Given the way that both elite and grassroots sport is funded and provided for, it is always extremely political. This is even before one discusses sport and identity, a subject that has come up at the games many times before.

This is the third time Scotland has hosted the event, having previously held them in Edinburgh in 1970 and 1986. As the games had its origins in the British Empire Games, the competition accordingly reflects the UK’s – and Scotland’s – relationships with empire and decolonisation.

Olympic protests

South Africa’s system of apartheid ensured that it was banned from appearing at the Olympics and World Cup from the 1960s until apartheid ended in the early 1990s. The 1976 Olympics in Montreal was boycotted by 25 African nations after the IOC failed to ban New Zealand, which had recently allowed the South African rugby team to play in the country.

The Olympics survived, and went on to navigate two major Cold War boycotts in 1980 and 1984. It would also have survived the mooted but somewhat piecemeal Sochi 2014 boycott in relation to Russia’s treatment its LGBT citizens.

South Africa left the Commonwealth in 1961, so there was no question of the nation appearing at the games. But the Commonwealth Games became a protest forum for member countries in the 1970s and 1980s against the fact that South Africa had admirers within the conservative political and sporting establishments of the empire’s white dominions. They continually invited South Africa’s rugby and cricket sides to give tours of their countries.

Not cricket

After the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) invited the country’s cricket team for a tour of England in the summer of 1970, a comprehensive boycott was inevitable for Edinburgh’s games that same summer. The South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee called on Britain’s former imperial dominions not to attend the games if the tour went through – which they duly threatened to do.

Initially games organiser Herbert Brechin, a former lord provost of Edinburgh, accused the nations of blackmail and stated that the games would go on without them. In private, the games’ executive board confronted him on his comments, believing that a boycott would bring financial ruin. Almost immediately, his comments on the matter became more conciliatory. What actually saved the games, however, was largely the Labour government of Harold Wilson putting heavy pressure on the MCC to cancel the tour.

Yet the ongoing support for South Africa within the former imperial white dominions ensured that the Commonwealth Games would continue to be subject to boycott threats. Nigeria refused to attend the 1978 games in Vancouver, for example.

Margaret Thatcher took a different line on South Africa. She believed in trading with the country, in direct contravention of the “boycott, divestment, sanctions” programme called for by the anti-apartheid community. When the authorities allowed a South African rugby tour in 1984, moves began within the Commonwealth Games Federation to ban England. In the end this fell apart because protesters could not secure enough votes in the federation to make a ban go ahead.

But then came the case of white South African long-distance runner Zola Budd. The 1984 Great Britain Olympic team provocatively included her in its line-up, a controversial addition championed by sections of Britain’s right-wing press. The inclusion of Budd, with very tenuous family connections to Britain, subverted South Africa’s international sporting ban. And, when she was included in the 1986 England team along with Annette Cowley, a South African-born swimmer, the threats increased.

The timing of the Games took place at a critical juncture: the African National Congress had recently stepped up its guerrilla campaign against the government of South African president PJ Botha, and the games were scheduled to take place just before the next meeting of Commonwealth nations. African, Asian, and Caribbean nations were keen to make an example of the Thatcher government, and one by one they pulled out of the Edinburgh games.

The Edinburgh conflict

Edinburgh’s left-wing district council wanted to show its commitment to ending apartheid. An all-out boycott would prove tough, so it turned towards non-cooperation. The city had already confronted these issues when Budd had come to race at the Dairy Crest Edinburgh Games at the city’s Meadowbank stadium on July 23 1985. On that occasion, the council had unfurled a banner that read, “Edinburgh – Against Apartheid”. This was construed as political advertising. The event, which was due to be aired live on Channel 4, had its television transmission cut just before it went to air.

As the chaotic 1986 Games lurched from one crisis to another, Thatcher was invited to the city by the organisers. She became the district council’s primary target, and it ordered her to keep out of Edinburgh. This proved impossible, but Labour councillors nevertheless joined members of the Anti-Apartheid Movement in a picket line at Meadowbank stadium and the athletes’ village. Council leader (now a Labour MP) Mark Lazarowicz stated: “We don’t want to have in our city a woman whose support for Botha means that she… has the blood of suffering people on her hands.”

Once past the cordons, Thatcher fared no better. A tour of the athletes’ village resulted in the PM being grilled by English rower Joanna Toch over her government’s recommendations six years’ earlier that athletes boycott the 1980 Olympics over the Cold War. Canadian high jumper Nathaniel Brooks accused Thatcher of embarrassing herself by coming to Edinburgh, stating: “There is no atmosphere in the village and I believe she must take the blame for a lot of that.”

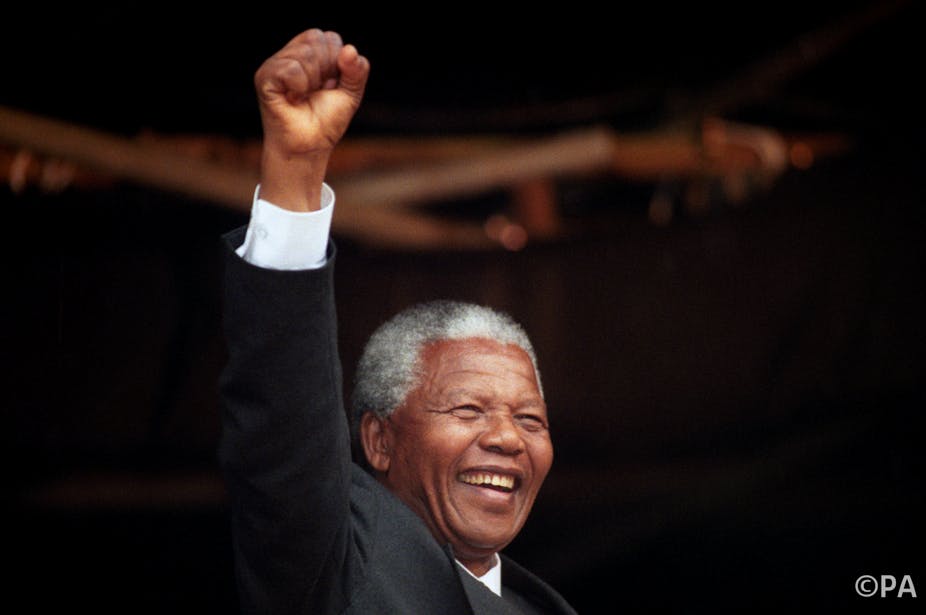

Scottish sport’s relationship with the South African question did not end in 1986. It’s easy enough to craft Scottish narratives of resistance to apartheid, which came to the surface for example during last night’s opening ceremony for Glasgow 2014 with the talk of that city’s support for Nelson Mandela’s liberation in the 1980s.

There was no mention of the fact that in 1989, the Scottish Rugby Union also invited South Africa’s team to the country. Those days of political boycotts have gone for the time being, but there is a a paradox about this year’s games all the same. In a year where Scotland holds a referendum on its place in the UK, a lot of work has gone into a sporting tournament that coyly acknowledges its place in the empire.