There are two ways of responding to deadly violence such as the school shooting in Connecticut.

We can respond violently, as a way of protecting ourselves from the fear and anxiety we feel. Or, we can respond by making ourselves more vulnerable, by putting aside the guns and aggressive behaviours that feed the cycle of violence.

The violent response is driven by the fear that someone will attempt to kill me or someone close to me. In order to protect myself I therefore need to be able to defend myself against, and kill, the person who might threaten me. According to this way of understanding violence, it makes perfect sense to demand that teachers be armed with guns.

The person who responds violently to violence finds it difficult to see that they themselves, or a member of their circle of family and friends, may be the person who initiates violence. Rather, the threatening mass murderer is always “other,” a random killer, a mentally ill person, an ethnic other. Uncertainty, fear and vulnerability are repressed or denied, and anger and murderous desires are projected onto the threatening “other”.

In the violent response, my sense of safety derives from my ability to inflict violence on the “other” who threatens me. It is very disturbing, indeed, to suggest that you might take away my ability to protect myself from the vulnerability I feel.

In contrast, the vulnerable response actively wrestles with fear and the desire to inflict violence. The vulnerable response recognises that we all have the capability, and sometimes the desire, to inflict great suffering on others in response to our fears and anxieties. Rather than being driven by these murderous desires, I search for alternative responses to my fear and murderous desires.

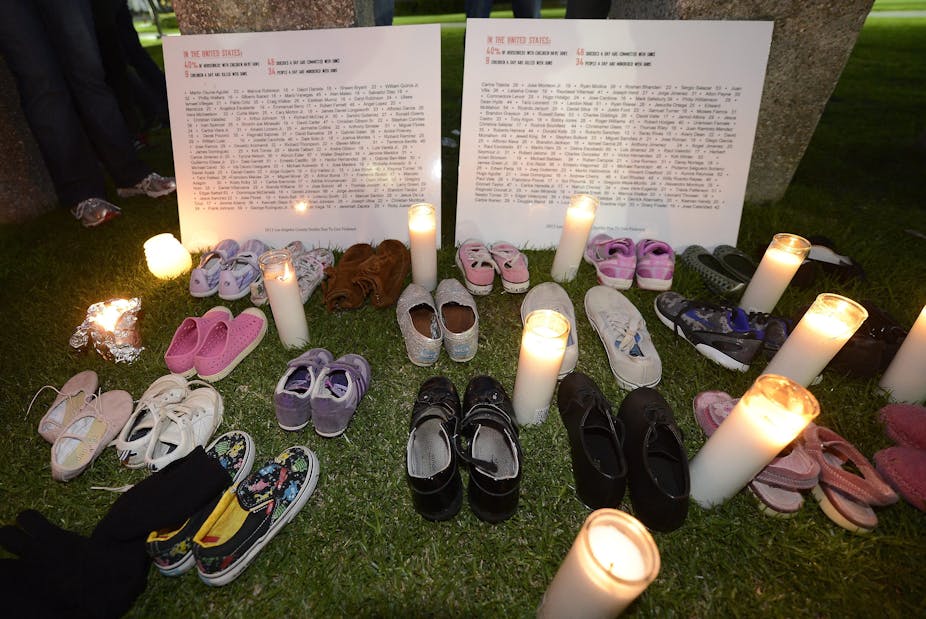

The person who chooses vulnerability keeps foremost in their mind the suffering that violence inflicts on others. My priority is to prevent or reduce suffering, even at the expense of making myself more vulnerable. From this perspective it makes sense to significantly reduce access to deadly weapons.

The person who chooses to be vulnerable, embraces their own frailty and the uncertainty that they feel. I choose to live with this vulnerability, rather than trying to overcome it. This takes great courage.

This description of different responses to violence draws on the work of Emmanuel Levinas. Levinas was responding to the violence of the Nazi mass murder of Jews. Judith Butler extends Levinas’ ideas in her comments about the US response to the September 11 tragedy. Her comments could equally be applied to the Connecticut school shootings:

Tragically, it seems that the US seeks to preempt violence against itself by waging violence first, but the violence it fears is the violence it engenders. … Suffering can yield an experience of humility, of vulnerability, of impressionability and dependence, and these can become resources, if we do not “resolve” them too quickly; they can move us beyond and against the vocation of the paranoid victim who regenerates infinitely the justifications of war.

These two types of responses are, of course, caricatures, or ideal types. Reality is much more complex and messy. Nonetheless, they are suggestive of things to consider in our responses to violence.

The difference between these two responses is a product of the way we understand ourselves emotionally. Statistics, logical argument, and carefully reasoned debate do not easily change these emotions.

Emotional self-understandings are culturally produced. As Jeffrey Alexander has noted, response to collective trauma is cultural work. The challenge is to find collective symbolic renderings of trauma that might help us escape the escalation and cycle of violence.

Anger and paranoia are popular in the mass media. Humility, precariousness, frailty and vulnerability are less popular. The angry hero’s story is an engaging narrative of a strong individual courageously overcoming obstacles, attacking, conquering, and violently subduing. The vulnerable narrative is more complex, acknowledging dependence and failure alongside achievement.

Public narratives that provoke fear and anxiety fuel the cycle of violence. They seek to escape vulnerability through destruction of the other, but only serve to facilitate the very violence they fear.

Self-understandings that embrace our fears and vulnerabilities lead us into more creative responses to a world that is often violent and increasingly uncertain.