Throughout his political career, Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson has been lauded as a “character”. He is portrayed as bungling through escapades with effable charm, as being prone to innocent gaffes and as lurching from one humorous episode to another. It would all be so very “Carry On” if the repercussions of his words weren’t quite so serious.

In August 2018 Johnson wrote an article in The Telegraph, in which he discussed the recent banning of the niqab, or full-face veil in Denmark. In it, Johnson described Muslim women as looking like “bank robbers”. He said he found it “absolutely ridiculous that people should choose to go around looking like letter boxes”. Johnson described the expression of Islamic faith as a “problem” and customs of Muslims as “bizarre and unattractive”. No action was taken against Johnson at the time. Conservative peer Sayeeda Warsi, who has long highlighted the issue of Islamophobia in the party, called it “business as usual”.

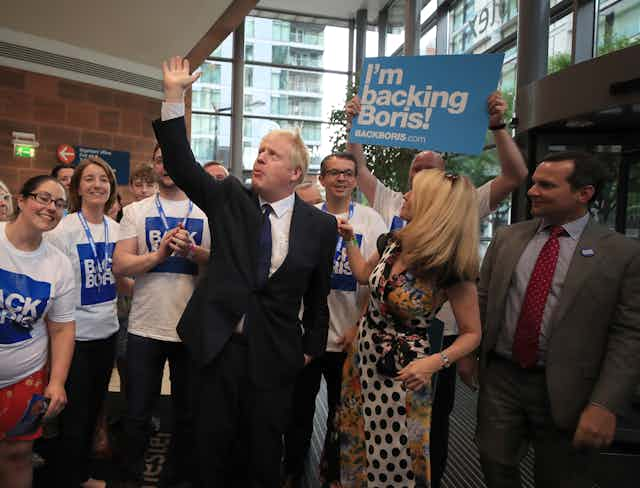

Now, Johnson is on the verge of becoming prime minister and the Conservative Party continues to deny it has a problem with Islamophobia. A recent poll showed that more than 43% of Conservative members would prefer not to have the country led by a Muslim. It also revealed that 67% of members believe the Islamophobic myth that areas of Britain operate under Sharia law. Sajid Javid never really stood a chance in this leadership contest. Successive Tory party members have been disciplined or suspended from the party for posting Islamophobic or racist content online (and then quietly readmitted and allowed to stand as potential election candidates).

Meanwhile, Johnson has downgraded his promise to hold an independent inquiry into Islamophobia in the Tory party if elected as leader. This will now be just a “general investigation”. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised. After all, what would an investigation into a Conservative Party that has elected a leader who calls niqabi women “letter boxes” actually look like?

In a televised BBC TV debate the contenders for leadership were challenged to commit to an independent external inquiry into Islamophobia in the Conservative Party. Javid put the other candidates on the spot, asking “shall we have an external investigation in the Conservative Party into Islamophobia?”. The agreement from the other candidates seemed reluctant. Jeremy Hunt contended that “racism was not restricted to any one political party”. Cool new guy, and ever the “diplomat” Rory Stewart, even found it difficult to call out Donald Trump’s blatant Islamophobic attacks on the London mayor, Sadiq Khan.

Islamophobia is and has long been a problem – both within the halls of power and on the streets of the UK. It’s not difficult to see how irresponsible sentiments and language used by politicians can influence opinions in our everyday public spaces. Nor is it too difficult to see how unscrupulous politicians are willing to take advantage of misplaced fears and moral panics over the “Muslim other”.

Following Johnson’s comments, Tell MAMA, the anti-Islamophobia charity which records anti-Muslim hate crimes, found a sharp rise in reports of abuse from women wearing headscarves or the face veil. They reported having scarves ripped off, being spat at and verbally abused, sometimes with the words Johnson used in the article – “letter boxes”.

Not sorry

Johnson has yet to apologise for the words used in his article, nor is any apology likely to be forthcoming. But political leadership comes with added responsibility. People do look to the words of political leaders and re-use them on the streets. What does Johnson’s continued popularity, among fellow Conservative MPs and party members say about accountability or responsibility in British politics?

It is grossly irresponsible to use Islamophobia to a political advantage. And yet, Islamophobia is a vote winner, even if that phobia is couched in catch all terms of the “Muslim problem” – a trope which includes fears of mass immigration and creeping Islamification. We just have to look at the rise of Trump, political campaigns across Europe, and indeed, the campaign for Brexit, if we doubt just how much currency the “moral panic” over the Muslim population has in current political climes. Johnson’s continuing popularity among the electorate shows that politicians are all too aware of the benefits Islamophobic rhetoric, especially when it seems to conform underlying prejudices, that the root of all social ills in Britain can be reduced to Muslims.

Johnson has often been touted as a “tell it like it is” figure, and trusted to champion the ordinary, average Brit. His comments on Muslim women were echoed across online Conservative Party forums, with comments comparing the niqab to an “SS Uniform” and the need to eradicate the “cancer of Islam and Middle Eastern cultures”.

Johnson was once described as a “poundland Trump” – a bit on the nose perhaps – but it’s possible to see how rising populism, and dog-whistle politics appealing to the lowest common denominator – rising anti-Muslim sentiments – are a sure currency during elections.

Niqab wearing Muslim women often bear the brunt of Islamophobia. Gendered Islamophobia – which takes into account intersections of race, religion, ethnicity and culture – shows that, overwhelmingly, Muslim women who veil are more likely to face anti-Muslim hostility, whether that’s verbal or physical abuse, because they are “visibly Muslim” . In 2018 statistics showed that veiling Muslim women remained number one victims of street level abuse.

What Johnson’s potential elevation to the highest echelon of British politics tells niqabi women is that, in the current political quagmire of nativism, populism and ethno-nationalism, anti-Muslim sentiments aren’t likely to hold you back, or impact negatively on political ambitions. In fact they’re likely to be rewarded.