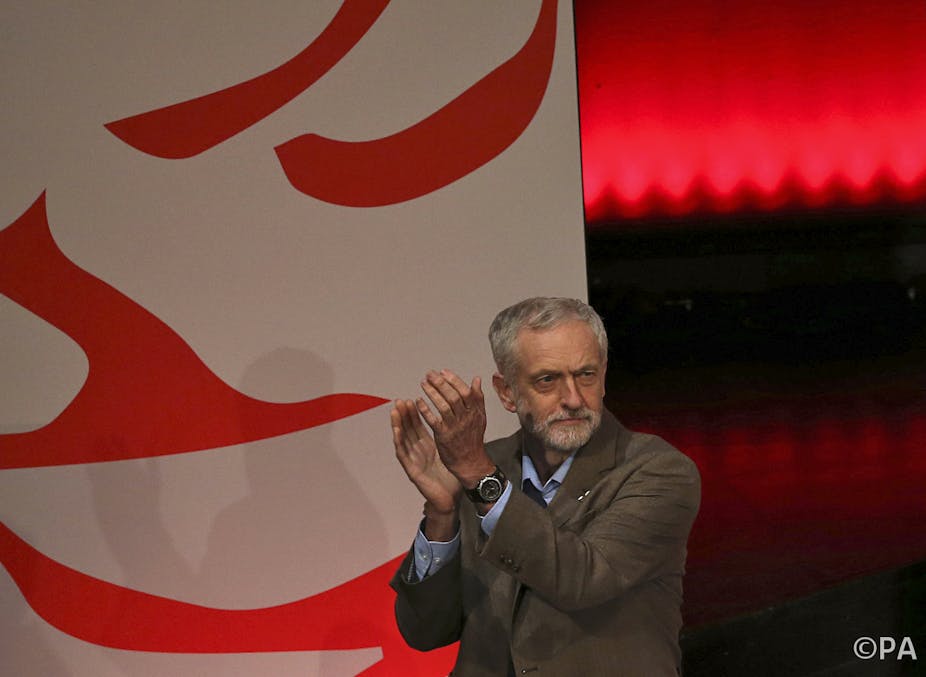

The unthinkable has happened. Jeremy Corbyn has won the Labour leadership election by a landslide, easily taking more than the other three candidates put together. With a huge groundswell of support from the several hundred thousand people who have joined the party since the last election, the radical democratic socialist has snatched Labour from under the noses of the establishment.

It comes at a time when the UK has never been more disillusioned with mainstream politics. The major parties are viewed as too similar, made up of representatives who are far-removed from the experiences of ordinary people – step forward Corbyn’s rival leadership contenders. What we are not used to is these perceptions affecting political participation. The way in which we used to register our discontent was by passively rejecting party politics. Only around 1% of the electorate are members of a political party, compared to nearly 4% in 1983 for example.

Corbynmania may be challenging this trend, however. In an extraordinary period in the history of the Labour party, an avowedly left-wing candidate has generated a level of support and enthusiasm that we don’t tend to associate with modern UK politics, or indeed with established democracies. The full implications of these events are as yet unclear but they may have sparked an appetite for a more participatory model of politics in this country.

At the end of 2014, Labour membership stood at 193,000, having not exceeded 250,000 since 2000. Then came Ed Miliband’s changes to the party rules for leadership contests, aimed at extending democratic engagement. These created a selectorate of three groups – members, supporters and trade union affiliates.

Supporters and full members have come to the party in large numbers, generating substantial fees in the process. Of the 554,000 eligible to vote in the current election – which is after the party’s weeding out of illegitimate sign-ups – 293,000 are full members (fees vary, but can be £50), 113,000 are supporters (fees £3), and the remaining 148,000 are trade union affiliates. While Corbyn has been most popular among the union sign-ups, he has enjoyed widespread support among all three groups.

On the face of it, participation in UK politics has obviously been enhanced by the Labour leadership campaign – albeit perhaps in a shallow form given it was possible to sign up for the price of a latte. The real test of engagement will be whether these £3 supporters remain involved. Harriet Harman has suggested this group will naturally convert to full membership to influence policy, but these are probably false hopes.

People power

The Corbyn surge may also have wider implications. The swell of enthusiasm for this radical candidate involves rejecting right-wing austerity economics, inequality and elitism, and it has the feel of a mass movement. Clearly the UK is not immune to forces that have already been evident in European and US politics. The Corbyn message has appeared authentic, sincere and consistent, not labels commonly attached to politicians.

Perhaps even more important has been its sense of hope and optimism, reminiscent of the Yes campaign in the Scottish independence referendum. A positive vision can be inspiring, particularly at a time when many citizens in the UK and elsewhere are desperate for some good political news. Corbyn recognises that popular trust in politics is critical and requires nurturing. This is why he advocates a Labour party built on genuine input from the grassroots.

Corbyn’s campaign has taken the shape of a traditional style of politics, namely the political meeting. He has addressed more than 100 meetings and rallies, with many spillover talks and many people turned away – further echoes of the Scottish Yes campaign – and this has combined with a modern, professional and energetic online campaign.

What we are observing in Labour politics might even have been inspired by events north of the border. Remember that Yes backers the SNP and Scottish Greens both experienced a dramatic increase in membership following the referendum. There was even a rise in membership of the heavily defeated Liberal Democrats following the general election. Note the break from the past here: until recently, membership increases were associated with election success, not failure.

A new politics?

Put this all together and it begins to look like we may be entering a new age of protest politics, born of deep disillusionment with the political mainstream. Voters on the centre-left may be persuaded that a viable alternative exists and politicians who can articulate this alternative might inspire a new generation – in a reversal of the politics that ended the social-democratic consensus of the 1970s.

Then again, we must bear in mind that the politics of party membership is unrepresentative of the electorate at large. What wins an internal party debate is unlikely to win a general election. Conventional wisdom suggests this will be protest to no end. That won’t stop the Corbynistas hoping that this is the beginning of a reshaping of the ideological debate in UK politics – and perhaps even a new model of democratic politics. But for them to be right we’ll still need to see the sort of sea change that has not happened in this country for a very long time.