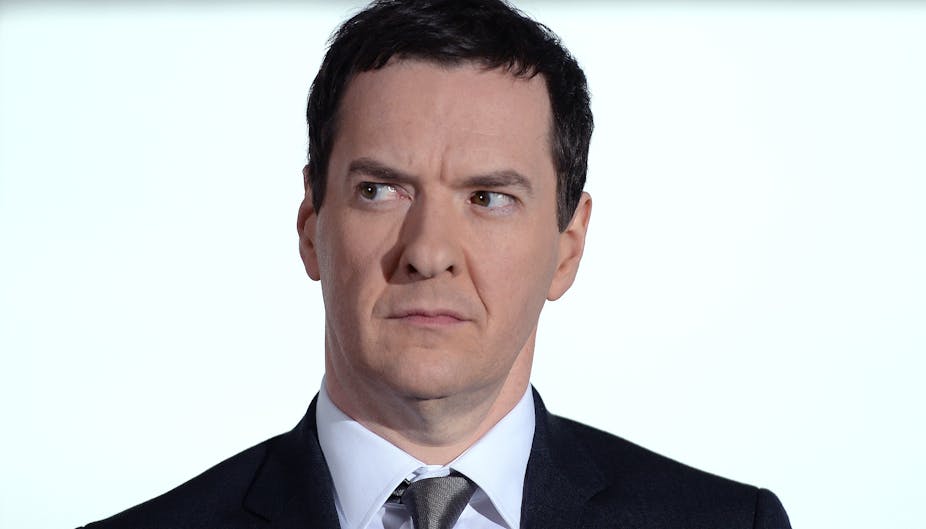

It’s nearly two and a half years since the moment which will, I am increasingly certain, be seen as a key turning point in British political history. Forget Brexit. I am talking, of course about Theresa May’s decision to sack George Osborne as chancellor of the exchequer on July 13, 2016. This moment was only conceivable because of that other moment, three weeks earlier, but it has shaped quite profoundly the political implications of the vote to leave the European Union.

I teach a course on economic policy-making, and my students will testify to the fact that I am mildly obsessed with the former chancellor. Barely a lecture goes by without me mentioning his enormous influence on the recent development of British economic policy, during a seismically significant period for the economy.

Let us be clear: Osborne’s economic stewardship was ruinous. Yet he is substantially better at politics than he ever was at policy. May’s decision to sack Osborne also had little to do with his record as chancellor, or indeed his opposition to Brexit. He was replaced by Phillip Hammond, who is as committed as Osborne to both austerity and EU membership.

Osborne’s Brexit

What Britain lost when Osborne was sacked was a focal point, within government, for soft Brexit. Hammond lacks the political skills, or alliances, to play this role. Osborne was never really loved by Conservative Party members – but he was respected. Had David Cameron decided against holding the EU referendum, as Osborne advised, then Osborne would have been the only serious candidate to succeed him as leader.

Osborne’s vision for the future of the British economy is, however, largely the same as that of the leading Brexiters. He was keen to recast the UK-EU relationship as an economic one. As Chancellor, he pursued “Global Britain” through the internationalisation of the City, and saw the EU’s new zeal for bilateral trade deals, enforcing deregulation, as consistent with, and indeed central to, his agenda.

Osborne’s understanding of the chaos that Brexit would cause explains his support for Remain, but as May’s chancellor, he would undoubtedly have seized the opportunity to push for a firm decoupling of the UK from the eurozone’s political integration, while situating Britain as the leading member of an emerging outer ring of the European single market.

This perspective has been thoroughly marginalised within the Conservative Party since 2016. But many of the party’s 2010 and 2015 intake of MPs – remainers and leavers alike – owe their careers to Osborne. It’s not difficult to imagine Osborne acting as a vital conduit between the prime minister and the parliamentary party.

Brexiters such as Boris Johnson know as well as anyone that leaving the EU will do little to advance the ideological agenda he shares with Osborne. He chose to lead the Leave campaign purely for political expediency, because rebranding himself as an authentic eurosceptic was his only hope of beating Osborne to the leadership or, more likely, once the referendum had been lost, securing a top job in a future Osborne cabinet.

Johnson has created a beast he lacks the werewithal to control. By leading the Leave campaign, he lent euroscepticism a veneer of centrist, cosmopolitan respectability. But without a coherent plan for soft Brexit emerging from the Conservative ranks, Johnson and co. have been increasingly caught between the rock of Theresa May’s vacuous vision and doomed leadership, and the hard place of Jacob Rees-Mogg’s jingoistic and economically illiterate ultra-Brexit.

The genesis of ‘no deal’

And thus we arrive at the absurdity of a no-deal Brexit. It has quickly become a political cliché, but it is worth restating that nobody voted for “no deal”. What the Leave campaign offered was a very comprehensive free trade deal as an alternative to EU membership. It was essentially an accelerated version of the path Britain was on anyway, as long as it remained outside the eurozone.

No deal was a fringe agenda, peddled only by marginal figures such as John Redwood. It only really entered the lexicon of mainstream politics after May’s Lancaster House speech in early 2017, in which she argued that “no deal is better than a bad deal”. How quickly we have forgotten what she was actually talking about. The “no deal” of the speech was referring to the prospect of a future trade arrangement – not the prospect of leaving the EU without a withdrawal agreement. The speech was a misguided and futile attempt to encourage the EU to negotiate both deals at the same time.

It was quickly consigned to irrelevance, as the EU understandably pointed out that unless Britain agreed an orderly withdrawal from the union, there could be no prospect of agreeing a new trade relationship. The EU cannot negotiate a trade deal with a country that is still a member of the bloc.

An orderly withdrawal meant, above all, finding a way to prevent Brexit wrecking the Irish economy, and jeopardising the Northern Ireland peace process – hence the need for an insurance policy (or “backstop”) should the trade deal take longer than two years to agree. Given that the Brexiters have frequently claimed that a new UK-EU trade agreement would be “one of the easiest in human history”, their indignation over the backstop is either senseless or duplicitous.

The lesser evil

In the absence of a genuine leader, coupled with a failure to communicate the difference between the withdrawal process and a subsequent trade deal, May has been cast as the chief advocate of soft Brexit, and vilified as a result. Yet her opposition to free movement of labour makes her vision for life outside the EU a lot “harder” than anything most of her Brexiter critics, who have few concerns about immigration, would have advocated.

Crashing out of the EU may be unthinkable, but that does not mean it will not happen. Osborne deserves his political wilderness, since his policies did so much to cause the divisions which produced the Brexit vote. His soft Brexit would, over the long term, probably have been just as destructive. But set against the avoidable tragedy of no deal, it might have been the lesser of two evils.