Ambulance call-outs to ice users have tripled in two years and harm from ice (also known as crystal meth) has risen higher than the previous peak in 2006 – a period known as [the “ice age”](http://www.abc.net.au/4corners/content/2006/s1593168.htm. These are the findings of a report I co-authored in today’s Medical Journal of Australia.

While overall meth and amphetamine use remains stable in the general population, ice use is rising among some groups of existing drug users. However, it’s unclear whether these users alone are driving the rise in ice-related harms.

You’ve probably heard of ice and crystal meth, but let’s take a step back and look at the group of drugs.

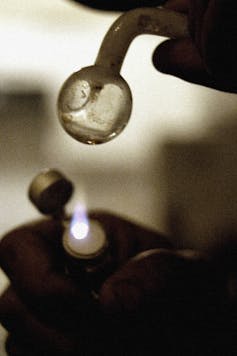

While “speed” is the street name for the powder form of both amphetamine and methamphetamine, “ice” or “crystal” specifically refers to the crystalline form of methamphetamine. Ice is generally smoked or used intravenously, leading to faster absorption and slower metabolism by the body, resulting in a more intense high.

The effects of amphetamine and methamphetamine range from increased energy, alertness and euphoria, to anxiety, paranoia, hallucinations and violence. Large doses can cause extremely high heart rate and body temperature, strokes and heart attacks; while long-term use may lead to dependence or even brain damage.

Piecing together the data

Meth and amphetamine use in the Australian general population [is high](https://theconversation.com/explainer-methamphetamine-use-and-addiction-in-australia-13280 compared with the United States or the United Kingdom, with 2.5% of Australians 14 years or older [reporting](http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=10737421314 use in the preceding year. This is double the rate of other developed countries.

Some studies suggest the proportion of Australians reporting recent use has been declining since 1998 - and the current reported proportion is the lowest in the past 15 years. But these estimates do not specifically ask about ice. And they don’t capture hard-to-reach populations such as dependent or poly-drug users, who take a combination of drugs to achieve the desired high.

Importantly, studies that address this paucity of evidence [show](http://ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/ndarc/resources/EDRS%202012%20national%20report%20FINAL.pdf rising ice use since 2009, with recent use almost doubling among Australians who regularly use ecstasy: 15% of ecstasy users also took ice in 2009, rising to 29% in 2012. Ice use among people who inject drugs has also increased, from 37% in 2009 to 54% in 2012.

Tracking the harm

With rising use comes rising harms. Our study found that from 2009/10 to 2011/12, meth and amphetamine-related ambulance attendances in metropolitan Melbourne doubled (from 445 to 880 cases), predominantly driven by rising ice-related attendances (from 136 to 592 cases).

The reasons for ambulance call-outs ranged from anxiety, paranoia or hallucinations to physical health problems, such as high heart rates, palpitations, gastrointestinal symptoms or injury resulting from assault, self harm or accidents.

The behavioural effects of ice, including confusion, agitation and aggression, adds to the complexity of paramedic assessment and treatment. More than three-quarters of ice and other meth and amphetamine-related attendances require transfer to hospital for further assessment in an emergency department.

We also found that in 2011/12, the rate of people seeking meth and amphetamine-related treatment was two to three times higher than in 2009/10, for both face-to-face treatment, including counselling and withdrawal programs, and telephone counselling.

Changing demographics?

But this many not be the full story. On the one hand, the characteristics of users for whom ambulances are called and those who attend drug treatment services have changed little. This suggests that the types of people using ice and other amphetamines may not be changing. Instead, existing users may be experiencing a greater number of harms.

On the other hand, anecdotal reports from treatment agencies and other sources suggest changing patterns of ice consumption, with greater availability, use and associated harms in regional areas where ice use has traditionally been low.

Emerging anecdotal evidence also indicates that use – and harm - is increasing among people in occupational groups not traditionally associated with stimulant use, such as young tradespeople and professionals. Little is known about how ice affects these emerging user populations; researchers and clinicians are particularly concerned about the interplay between physical, behavioural, mental health and social problems.

We know that ice-related harm is growing. But given we’re dealing with research data and anecdotal evidence, questions remain about the factors that might be driving the rise in harm: whether it’s new populations of users, more harms for existing users, or changing patterns of use.

It’s also unclear how these rising harms will impact on the community, particularly for delivering services to high-risk groups.

To minimise harms, we need to promote a greater understanding of ice use in the community to enable appropriate prevention, intervention and service responses that are evidence-based and target those who are most at risk.