Last month, cultural appropriation became a big issue in the Canadian publishing and media world after the trade association magazine, Write published a special issue featuring work by Indigenous authors. The editor of the magazine, Hal Niedzviecki, wrote a glib editorial in defence of cultural appropriation.

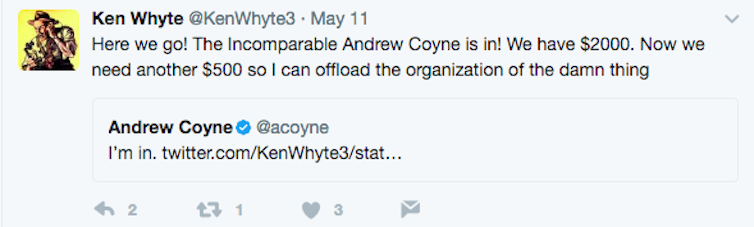

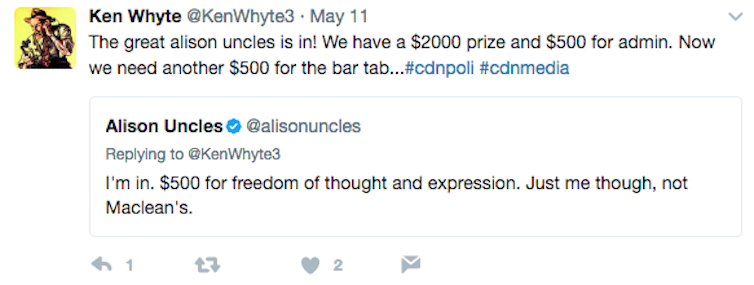

Niedzviecki resigned and immediately after Canadian media executives irreverently pledged donations toward a “Cultural Appropriation Prize” on late-night Twitter in support of his editorial. The main thrust of the offending Twitter conversation seemed to be that white media elites and writers felt they were under threat of being censored.

White media elites felt they were under threat of being censored

The argument was framed in the high-minded rhetoric of freedom and creative license, but underneath that thin veneer, it relied on a belief in white victimization that you’d expect from fringe white nationalists rather than the top one per cent of Canadian mainstream media.

As a scholar of the book publishing industry, I can say with empirical authority that the notion of white people being under threat in publishing crumbles in the face of evidence. As I show in my new book, Under the Cover: The Creation, Production and Reception of a Novel, book publishing is the same as it ever was: it is white-dominated and it’s easier for white people to gain entry to it. Although my research on book publishing is based in the United States, as the sociologist Sarah M. Corse has shown, the U.S. and Canadian book publishing industries are deeply intertwined, and more often than not are actually the same industry.

If you want to throw an all-white party, invite book publishers

To understand the real barriers to book publishing, the most important places to look are the points of entry themselves. In publishing, those access points are guarded by literary agents and acquisition editors. They are the gatekeepers, and across the U.S., the gatekeepers of publishing are 95 per cent white. If those gatekeepers had their own state, it would be the whitest state in the U.S. If they had their own country, it would be the whitest country in the world. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, if you wanted to throw a party with only white people in attendance, you’d invite veterinarians, farmers, mining machine operators and book publishers.

While it is hypothetically possible that those white gatekeepers could privilege racialized authors over white ones, the reverse is actually true. Regardless of their race, about 38 per cent of the 1,200 literary agents in the United States I’ve studied show an equal interest in representing “general” fiction. But when that fiction covers topics of ethnic and multicultural diversity, white agents run for the hills, with only 15 per cent willing to even take a look.

Racialized authors work harder and submit more widely

Simply put, racialized authors — who are overwhelmingly the ones writing ethnic or multicultural fiction – are the authors who face longer odds of getting published. And like people of colour across different occupations, research shows these authors respond by working harder and submitting more widely, putting more effort and sweat equity into their searches than their white counterparts. This is done in an effort to balance out the discrimination they know they will face.

Yet even in my interviews with racialized authors who could secure publishing contracts, they described a process in which their novels were ping-ponged back and forth between being “too racialized” at first, and then not racialized enough.

Racialized authors are often asked to dumb down their stories

As a Black, southern literary writer explained to me, he had to “dumb down” his manuscript populated by Black southern characters because his editor didn’t believe “people talk that way” – the cultural specificity and accuracy of his novel was whitewashed out.

In the marketing and promotion stage, however, even after having their novels culturally denuded, racialized authors found themselves ghettoized and pigeon-holed again. One African-American novelist told me the painful story of her fears that her work of literary fiction would be pushed back into the “African American interests” section of bookstores rather than being shelved with the rest of the literary fiction.

A widely celebrated Chinese American literary novelist sardonically told a racially diverse room of her fans about a conversation with her publisher: “I told them: ‘Just promise me you won’t put any lanterns or fireworks on the cover because these are stories about people. Yes, they happen to be Chinese, but they’re stories about people.’ So as you’d expect, it has goldfish on it. The only thing I left them.”

Don’t forget these are the success stories. These are the racialized authors who make it.

Regardless of the statistically and experientially indefensible claims made by Cultural Appropriation Prize supporters, the real “race problem” in book publishing is the same as it is all over the world: white people are blessed with large and small advantages that they may not even understand. Racialized people are penalized with large and small disadvantages that they have no choice but to understand. If you don’t know where to stand on the cultural appropriation debate, just look at the numbers.

This article has been updated to correct the timing of Niedzviecki’s resignation. He resigned before the Twitter affair, not after.