This is an article from Curious Kids, a series for children. The Conversation is asking kids to send in questions they’d like an expert to answer. All questions are welcome – serious, weird or wacky!

Where does the oxygen come from in the International Space Station, and why don’t they run out of air? – The students of class 3E, Ferny Grove State School, Brisbane.

That’s a really good question. The short answer is the astronauts and cosmonauts (that means a Russian astronaut) bring oxygen from Earth, and they make oxygen by running electricity through water. This is called electrolysis.

The air and water on the Space Station all originally came from Earth. Astronauts and cosmonauts transport these vital supplies to the Space Station when they travel there on Soyuz capsules (a type of spacecraft). Astronauts and cosmonauts also receive supplies from uncrewed spaceships, such as the Russian Progress and American Dragon. Uncrewed means with no people on board.

But fresh supplies from Earth aren’t enough to sustain the Space Station. That means if you’re onboard the Space Station you are really, really into recycling.

Read more: Curious Kids: My tooth fell out. Why is it so spiky on the bottom?

The Space Station’s water recycling system produces pure drinking water from waste water, sweat and even urine. In the words of astronaut Douglas Wheelock, “Yesterday’s coffee is tomorrow’s coffee.”

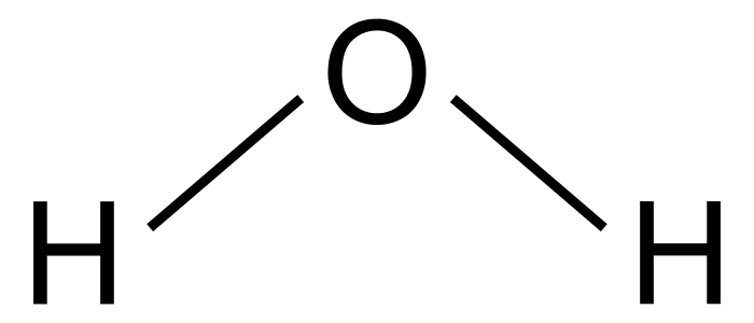

Water, which is made of oxygen and hydrogen atoms bonded together, is also used to maintain oxygen supply on the International Space Station. Using a process called electrolysis, which involves running electricity through water, astronauts and cosmonauts are able to split the oxygen from the hydrogen.

By the way, do NOT try this at home. Water and electricity do not mix, normally, and it can be very dangerous to try.

Electricity is one thing on the Space Station that doesn’t come from Earth, as the Space Station’s vast solar panels convert sunlight into power.

Read more: Explainer: the International Space Station

But what’s done with the hydrogen that’s left over? Using some chemistry and smart thinking, they’re actually able to turn it back into water!

The hydrogen is combined with carbon dioxide (that the astronauts and cosmonauts breathe out) to produce water and methane. So now there’s some more water to drink, while the methane is simply waste that is blown out into space through special vents.

So if you get a chance to see the Space Station tonight, you can marvel at many things.

Marvel at a spaceship travelling more than seven kilometres every second. Marvel that you can see where people live 400 kilometres above the Earth. And marvel at recycling that keeps people alive in the harsh environment of space.

Read more: What medicines would we pack for a trip to Mars?

Hello, curious kids! Have you got a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to us. You can:

* Email your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au

* Tell us on Twitter by tagging @ConversationEDU with the hashtag #curiouskids, or

* Tell us on Facebook

Please tell us your name, age and which city you live in. You can send an audio recording of your question too, if you want. Send as many questions as you like! We won’t be able to answer every question but we will do our best.