How lonely it is, to lose someone. And always, how unexpected. Strange that human beings have been on the planet for at least 200,000 years – and still death takes us by surprise. It’s an absence that we’ve never quite become accustomed to. The notion of our own deaths is a spectre we can never quite imagine, seeming a rather absurd joke. Meanwhile the deaths of those we love plunge us into black isolation, a dull bubble of grief that afflicts us like an illness.

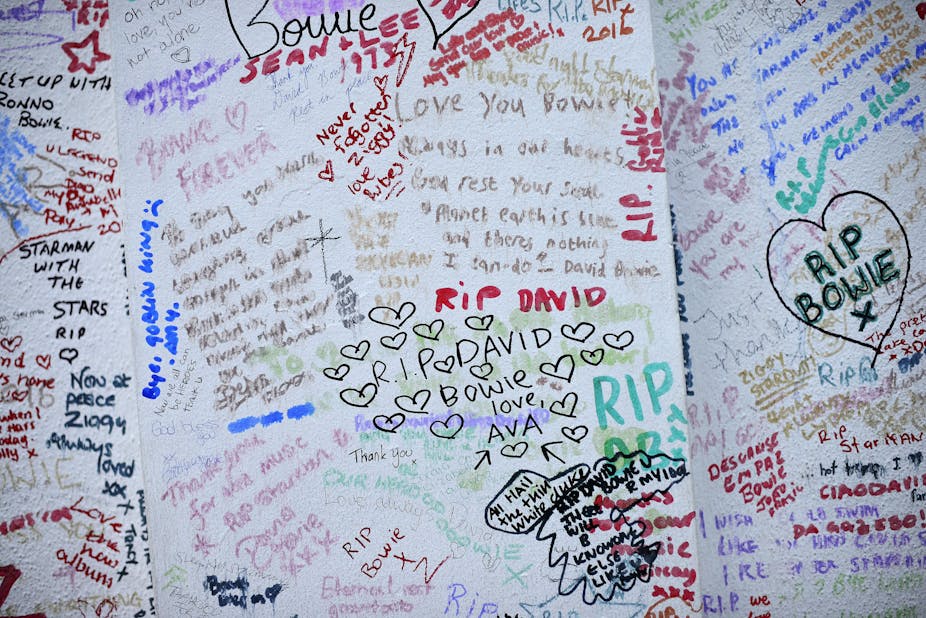

The deaths of David Bowie and Alan Rickman have resulted in emotional outpourings of shock and collective grief that have, it seems to me, filled more column inches and social media hashtags than the rest of the week’s news put together. The loss of Bowie in particular, who courted headlines just days before with the release of his album Blackstar, has sparked something approximating a national state of mourning. Followed so closely by the death of Rickman, there is a perception that British cultural life has suffered a major blow; the loss of these two iconic figures standing, in the collective psyche, for something cruel and unusual.

I confess that I have not been a particular fan of either of Bowie’s or Rickman’s work, and so the reaction is a phenomenon I’ve observed with the curious, but impartial, eye of an outsider. Of their respective repertoires, the two works with which I am most familiar are, coincidentally, implicitly concerned with death: Bowie’s 1980 hit Ashes to Ashes and Rickman’s role in Anthony Mingella’s 1990 film Truly, Madly, Deeply.

I was around 15 when I first saw Truly, Madly, Deeply. Rickman plays a ghost who returns to help his former lover – played by Juliet Stevenson – cope with a grief so intense that her life has been rendered unbearable. As a teenager, with limited experience either of love or loss, the plot failed to register a substantial impact. It passed quickly into the recesses of unmemory.

But revisiting the film as an adult was a different experience. Stevenson’s portrayal of the devastations of grief is unquestionably one of the finest, and starkest, ever committed to celluloid. And against today’s backdrop of what amounts to a public display of mourning, I’m reminded how at odds these public expressions of grief are with the private reality of mourning.

Because, collectively, we misunderstand the nature of death when we shake our heads and mutter over those who have left planet Earth, as if this is a great tragedy for them. It is not. It is a tragedy for those who are left behind. It is, and always has been, the living who suffer – not the dead.

Alongside loneliness and guilt – all the things we wished we’d said, or hadn’t said – comes an unexpected adjunct: fear. It was C S Lewis who wrote famously that no-one had told him how much grief felt like fear. Little wonder, then, that so much of what scares us is linked to the perpetual spectre of death.

And – as with Truly, Madly, Deeply, where the longed-for revenant, played by Rickman, soon becomes an uncomfortable guest – we are reminded to be careful what we wish for. Anyone who grieves will tell you that forefront in the psyche is the hopeless wish for the return of the one who is lost. That this desire is central to our collective psyche is evidenced by the defining Western creed of the past 2,000 years: that of Jesus Christ, who died and returned three days later, the cross signifying his eternal resurrection.

But elsewhere on our cultural landscape, the spectre of the revenant is a less welcome visitor.

In British folklore, a memorable example of the unwelcome revenant comes in the form of the demon lover – a young man lost at sea and who returns to wreak revenge on his former lover, whom he considers faithless for taking a new husband. In W W Jacobs’s short story, The Monkey’s Paw, an elderly couple wish for the return of their dead son, only to be horrified when the ghostly revenant comes banging on their front door. In Toni Morrison’s celebrated novel Beloved, a dead child returns to the living as a decidedly corporeal adult, and consumes everything in sight.

If cultural symptoms are anything to go by, it seems that, despite our increasing Western secularism, our anxieties and ambivalences regarding death – the great leveller – remain. Privately, we grieve for those we’ve loved. Publicly we grieve for those we’ve never even met – an anaesthetic form of mourning that allows us to play on the surface of death and its rituals without having actually to feel it – either truly, madly, or deeply.

But if it is resurrection we seek, then surely we can have it. Technology creates its own ghosts; and at the push of a button we can return the dead to life. Again, and again, and again …