Despite the enormous success of the environmental movement in the 1960s and 70s, we have fundamentally failed to use each of those battles to broaden the public understanding of why we were battling. It wasn’t just the power of environmentalists against developers, environmentalists against the oil industry. It was because we had a different way of looking at the world.

Environmentalism is a way of seeing our place within the biosphere. That’s what the battles were fought over. But we have failed to shift the perspective; or in the popular jargon, we failed to move or shift the paradigm. We are still stuck in the old way of seeing things.

I come to many of the politicians and corporate executives that environmentalists have been fighting all these years. They are driven by a totally different set of values, by the drive for profit, for growth, and for power. In that drive, they fail to see the bigger picture that environmentalism informs us about.

Look at the largest corporations like Apple, Walmart, Shell, Exxon, Monsanto – they are bigger and richer than most governments. And we treat them as if they are people. They are corporations, they’re not people. Why do we allow them to fund politicians, for God’s sake? They’re not people.

Politicians are running to look out for our future. But because corporations have the wealth to fund to a massive amount, after an election, guess who gets in the door to talk to the ministers and the elected representatives? It’s corporations. What we find is that governments now are being driven by a corporate agenda, which is not about our wellbeing and our happiness and our future.

Politicians today have very few tools with which to shape behaviour in society. One of the tools they do have is regulation. You set targets and you pass laws mandating them. And of course they are hated and fought tooth and nail by corporations – largely successfully.

Another tool they have – an enormous tool — is taxation. Taxation can be used to tax the things that we don’t want and pull the taxes off the things that we do want to be encouraged. We know that taxes work as a way of changing human behaviour. The carbon tax — putting a price on carbon — is by far the most effective way to begin to get corporations, to get companies, to get people to reduce their carbon footprint.

Your new Prime Minister ran on a promise to eliminate the carbon tax. I have no doubt he is going to do that, and will probably make this politically toxic now for at least a decade before it will be able to come back on the agenda. And this, of course, is just what corporations have wanted. But it works.

In Canada, we have the same kinds of arguments. We argue: oh, we’re a northern country; if we try to begin to reduce our carbon footprint it will destroy the economy. But we don’t look at what’s happening in a country very much like Canada – Sweden - a northern country which imposed a carbon tax in 1992.

They now pay $140 a ton to put carbon in the atmosphere. They’ve reduced their carbon emissions by 8% below 1990 levels, which is beyond the Kyoto target, and during that interval, their economy grew by more than 40%. So all this argument that we can’t afford to put a price on carbon – it will destroy the economy - is just what the corporations want believed and said.

There is in Canada a legal category where people can be sued and thrown in the slammer, called wilful blindness. If people in positions of power deliberately suppress or ignore information that is vital to the decisions they’re making, that is wilful blindness. I call it more than wilful blindness. I call it criminal negligence because it’s a crime against future generations, to avoid facing the reality.

That is what Mr Abbott is doing, by cancelling the (Climate) Commission, by firing Tim Flannery. It is criminal negligence through wilful blindness.

In my country we have a government that, I am ashamed to say, is even more intensely on this path because it has been in power longer than Mr Abbott. Stephen Harper, our Prime Minister, was a big admirer of John Howard and of George Bush, and he has cancelled virtually all research going on in Canada on climate change.

He has muzzled government scientists: they are not allowed to speak out in the public, even in areas in which they are expert, unless they are first vetted by the Prime Minister’s office. Scientific papers must go through the Prime Minister’s office before they are allowed to be submitted for publication. So we’re now getting science being moulded to fit a political, ideological agenda. He is laying off scientists in sectors like atmosphere research, forestry, and fisheries. So we can go into a very uncertain future basically blind.

In the book 1984, George Orwell speaks of “newspeak”, that when you can convince people that black is white and that war is peace, you can tell them anything. And what better way to allow people to believe whatever you say, by shutting down all avenues of serious, hard information.

How can we make truly informed decisions if the scientific community itself is shut down? I say to you, that in your society scientists better be up on the ramparts making sure you don’t fall on the path that Canada is on right now. When politicians are relieved of having to pay attention to real information – to science – they can base their decisions on what: the Koran? the Bible? My big toe has a bunion?

As a Canadian, I beg Australians to think hard on what’s happening in Canada, and please avoid that in your country.

So what do we do? For years in British Columbia, I’ve battled the forest industry over their clear-cut practices. To ward off these big battles, the British Columbia government set up a series of round tables where all of the stakeholders with a vested interest in a feature of that forest could come to the table and you’d then negotiate. They’re doomed to fail because what you do is you are fighting for your stake. Ultimately, what results is compromise. I just don’t think we’re at the point where we can compromise.

I’ve been asked by the vice president of Shell to meet with other environmentalists and his executives to talk about future energy strategies. But again, it was all couched within the perspective of “how do we pay for this” and “what is the economic cost of doing the right thing”? Same thing, the CEO of a consortium of tar sands companies, visited me and said: “will you talk to me?” And I said: “sure, I’m happy to talk, but I’ll only talk to you if we can agree on certain basic things. I don’t want to fight anymore. There’s no point fighting. Let’s start from a point of agreement.”

So, how about this? How about starting by saying, we are all animals, and as animals our most fundamental need, before anything else, is clean air, clean water, clean soil, clean energy and biodiversity.

But we’re also social animals, and as social animals, we have fundamental needs. What are our most fundamental social needs? Our most fundamental social need, it turns out, to my amazement, is love. Now, I’m not a hippie-dippie whatever. If you look at the literature, our most fundamental need for children is an environment of maximum love, and that they can be hugged, kissed, and loved. That’s what humanises us and allows us to realise our whole dimension.

If you look at studies of children growing up under conditions of genocide, racism, war and terror, children deprived of those opportunities, you find people who are fundamentally crippled physically and psychically. We need love, and to ensure love, we need to have full employment, and we need social justice. We need gender equity. We need freedom from hunger. These are our most fundamental needs as social creatures.

And then we’re spiritual animals. We emerged out of nature and when we die we return to nature. We need to know there are forces impinging on us that we will never understand or control. We need to have sacred places where we go with respect, not just looking for resources or opportunity.

I believe we are doomed to failure unless we come together to agree on what our most basic needs are. And then we ask: how do we create an economy; how do we make a living; how do we keep viable strong communities?

We’re doing it all the wrong way, because we take ourselves so seriously. And we think we’re so smart we create things that dominate the discussions. That’s the challenge and what has to change.

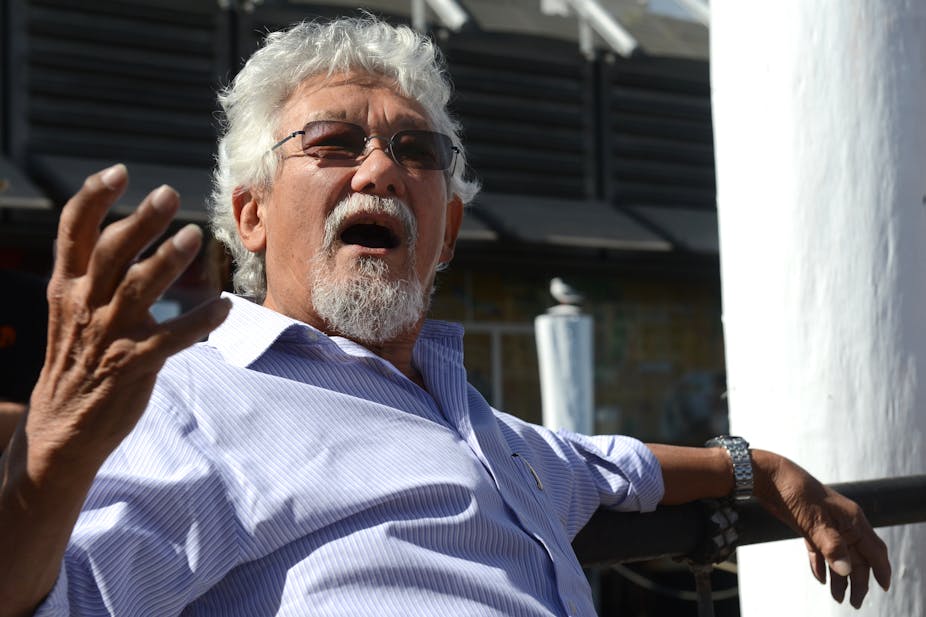

This is an edited excerpt from the 2013 Jack Beale Lecture on the Global Environment, “Imagining a sustainable future: foresight over hindsight”, delivered by Dr David Suzuki at the University of New South Wales on Saturday 21 September 2013.

To view David Suzuki’s speech in full, click here.