In Australia, there is an ongoing debate around the right for same-sex couples to marry. The majority of laws discriminating against lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people were repealed in 2008. Earlier this year, the Sex Discrimination Act (1984) was also amended to prohibit discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, gender identity or intersex status.

In order for LGBT people to achieve full equality, Dutch sexual orientation law expert Kees Waaldijk suggests that five steps must be completed. These are: decriminalising consensual sex between adults of the same sex; equalising the ages of consent; enacting anti-discrimination legislation; legally recognising same-sex relationships; and legally recognising same-sex parents.

There are parts of Australia that do retain some areas of discrimination against LGBT persons, including adoption of children by same-sex couples, and in Queensland, the continued existence of the “gay panic defence”. However, although homosexuality itself is no longer a crime, some men do still carry the burden of convictions they received in that era.

Australia has completed four of the five stages needed in order to achieve full equality for LGBT people. It is the fourth - not the fifth - stage that we are stuck on.

However, there are 76 countries where LGBT persons have not even completed the first step towards achieving equality. In these countries, consensual same-sex conduct is still a criminal offence attracting significant prison sentences - and in some countries, the death penalty.

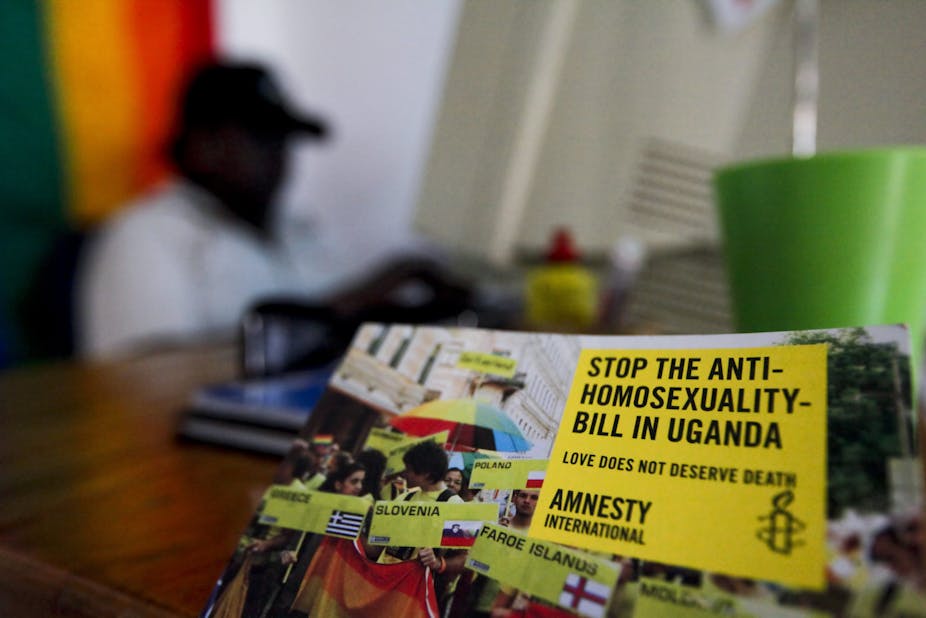

In recent years, many countries have endeavoured to further criminalise homosexuality, including Uganda, Liberia and Nigeria, with increasing instances of active enforcement.

In December 2012, a Cameroon appellate court upheld a three year jail sentence imposed on Jean-Claude Roger Mbede for “homosexuality”, on the basis of a text message he sent to another man. In Malawi in 2010, a judge imposed the maximum sentence of 14 years in prison with hard labour on a gay couple convicted of gross indecency and unnatural acts, after holding an engagement ceremony.

It is an indictment on the British Empire that of the 76 countries that still criminalise homosexuality, over half were once part of that empire and retained the anti-sodomy laws when they gained their independence. As a result, 41 of the 54 Commonwealth states still criminalise homosexuality, including neighbours of Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, the Solomon Islands, Malaysia, Singapore, and Sri Lanka.

Therefore, with the biennial Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) taking place in Sri Lanka in November this year, it is timely to ask: what, if anything, should Australia be doing to try and bring an end to the criminalisation of homosexuality in other Commonwealth nations?

CHOGM last met in Perth in 2011, and at that time ruled out supporting a Commonwealth-wide decriminalisation of homosexuality despite being urged to do so by Australia’s then-foreign minister Kevin Rudd. Indeed, agreement could not even be reached to publish the report by the Commonwealth Eminent Persons Group that looked at how the Commonwealth could be reformed. The report, which included input from former High Court justice Michael Kirby, apparently recommended the lifting of bans by all member states outlawing homosexuality.

If agreement could not be reached on decriminalising homosexuality when CHOGM was held in Australia, what are the prospects when it is held in one of the countries with anti-gay laws?

There is some cause for hope. For one, since the last CHOGM, a new organisation named Kaleidoscope Trust has been formed to work towards the repeal of all laws which criminalise individuals on the basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

Although Kaleidoscope Trust is based in the UK, an Australian branch, known as Kaleidoscope Human Rights Foundation has been formed to focus on reform in the Asia-Pacific region. This year, the Kaleidoscope Human Rights Foundation will be sending a representative to the Commonwealth People’s Forum - held immediately prior to CHOGM - which culminates in a roundtable dialogue between civil society representatives and foreign ministers attending CHOGM.

However, even if we witness steps towards decriminalising homosexuality in Commonwealth countries, that still leaves 35 non-Commonwealth countries with laws criminalising consensual same-sex sexual conduct. Mechanisms such as the individual complaints system run by the UN Human Rights Treaty Committee may be useful to advance reform.

There is also the power of dialogue within diplomatic circles. It remains to be seen if Australia’s new foreign minister Julie Bishop is willing to use her position to influence foreign leaders to move towards respecting the human rights of sexual minorities.

There is a long way to go before LGBT persons in many parts of the world pass through each of the five steps necessary to achieve equality. Australia has an opportunity at CHOGM - and other international gatherings - to clearly and firmly encourage the leaders of the 76 countries to at least take the vital first step.