Now it’s the Coalition that’s being accused of a “retiree tax”.

As interest rates have come down over the past four years, the rate that retirees are “deemed” to have earned for the purpose of the pension income test hasn’t budged, meaning that although retirees have been earning less (in some cases a good deal less), they haven’t been getting more access to the pension.

Depending on how you look at it, it’s either been making a mockery of the idea of an income test, or making the test more restrictive.

So how did it happen? Why is income “deemed” rather than actually measured when determining eligibility for government benefits, and is the system hopelessly compromised?

It’s important to understand what deeming is and where it came from if we are to understand the debate that will ensue when the government completes its review of the deeming rate in the next few weeks.

Where did deeming come from?

Modern day deeming was introduced by former prime minister Paul Keating in his final budget as treasurer in 1990.

As he explained in that budget speech:

many pensioners still disadvantage themselves by holding their savings in accounts that pay little or no interest

He was being diplomatic. It was widely believed that many retirees deliberately earned low rates on their savings in order to qualify for the pension or get a bigger pension. It cost the government money (while making the banks money) and it cost many of the pensioners money, because they lost more in interest than they gained in pension – although for those that used low earnings to ensure they at least got some pension, the associated benefits cards made it worth it.

From March 1991 cash and deposits were to assumed to be earning at least 10%, whatever they actually earned. If they earned more than 10% they were treated as earning more.

Except for the first A$2000. That was treated as earning only what it did, because many pensioners held small savings in low interest accounts for day to day purchases.

How has it changed?

Deeming is different today. It applies to more assets, including gold,

managed investments, superannuation account-based income streams and listed shares; and it is used to assess eligibility for more benefits, including veterans and disability pensions.

And it’s no longer a win-win for the government. If someone earns more than the deeming rate, their income is assessed at only the deeming rate.

In the words of the department of human services:

if your investment return is higher than the deemed rates, the extra amount doesn’t count as your income

There are two rates: one for the first $51,800 of financial assets (for a couple, the first $86,200) which is currently 1.75%, and the other for those assets in excess of that amount, which is currently 3.25%.

The threshold climbs in line with the consumer price index each July.

(In its first budget in 2014 the Abbott government tried to cut the threshold to $30,000 for singles and $50,000 for couples but was thwarted by the Senate.)

We deem by whim…

But there’s nothing automatic about setting the rates. It’s up to the government (specifically the minister for families and social services) to adjust them, or not, as it sees fit.

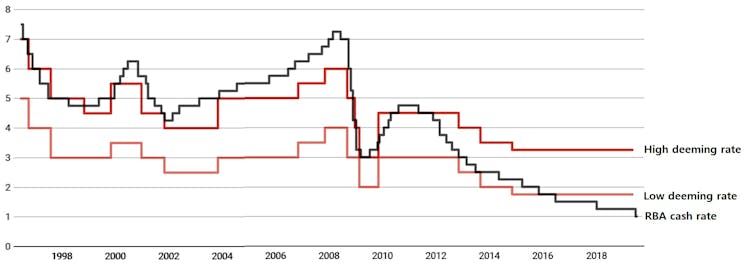

Both the high and low deeming rate used to be below the Reserve Bank’s cash rate (with the low rate typically 1.5 to 2 percentage points below the high rate), but after the cash rate dived in 2016 they have been left above it, in the case of the low rate, for the first time ever.

The high deeming rates mean many applicants are being means tested on income they haven’t received.

Deeming rates versus RBA cash rate, 1996 - 2019, per cent

…leaving rates curiously out of whack

Back when the deeming rates were lower relative to deposit rates, each of the big four banks offered “deeming accounts” that paid the deeming rates.

Today none of them do. They are not allowed to call accounts deeming accounts unless they pay the deeming rate, so instead they have retitled them “retirement accounts”.

The National Australia Bank’s retirement account (closed to new customers) pays just 0.20% for the first $10,000, well below the lowest deeming rate of 1.75%. The ANZ and the Commonwealth pay 0.25%. Westpac pays 0.3%. If you have more than $250,000 on deposit it pays 1.5% on the part above $250,000, which is still lower than the lowest of the two deeming rates.

Read more: Why pensioners are cruising their way around budget changes

Labor believes that not cutting deeming rates since 2015 has saved the government more than $1 billion per year in pension payments. It’s a significant portion of the $7.1 billion surplus it has forecast for 2019-20.

That is probably why the government has said it will take its decision about rates to its expenditure review committee, in what amounts to an admission that those decisions have as much to do with government finances as they do with treating applicants for pensions fairly.

There’s actually a case for extending deeming

As unrealistic as deeming rates have become, there’s a case for extending their use.

At the moment applicants for the pension face two means tests: one for assets and one for income.

Both the Henry Tax Review and the Abbott government’s National Commission of Audit recommended replacing them with a “merged means test” of the kind Australia had up until the 1970s.

Instead of an assets test, all assets would be deemed to earn a prudent rate of return; among them cars, holiday homes, investment properties, and high-value family homes.

The Commission put the case this way:

Exempting the principal residence from the means test is inequitable as it allows for high levels of wealth to be sheltered from means testing. For example, under current rules a single person who owns a $400,000 house and has $750,000 in shares ($1.15 million in total assets) would not be eligible for the pension, while a similar person with a principal residence worth $2 million and $100,000 in shares ($2.1 million in total assets) would be able to claim a pension at the full rate.

It’s a worthwhile idea whose time might come, but it is unlikely to come while deeming rates are seen to be unfair and capriciously set.

The government has an opportunity to restore confidence in deeming and pensions. The decisions it is about to make will show how important it thinks that is.

Read more: Words that matter. What’s a franking credit? What’s dividend imputation? And what's 'retiree tax'?