Digital networks and databases appear to crush historical distance. Archives of war increasingly come to us. A simple YouTube search throws up a chaotic mix of official and unauthorised, user-generated content, from helmet cam footage to images of snipers in the field.

But this immediacy, volume and pervasiveness can mean less reflection. The rawness of media memory distills a history without horizon and without hindsight. The sheer scale and complexity of digital data as primary source creates an immediate but unwieldy archive. It also hides what is really lost in paper’s demise.

And now the official guardians of military documents are going digital we should consider the future prospects for what are the prospects for the future of the history of warfare?

The making of history

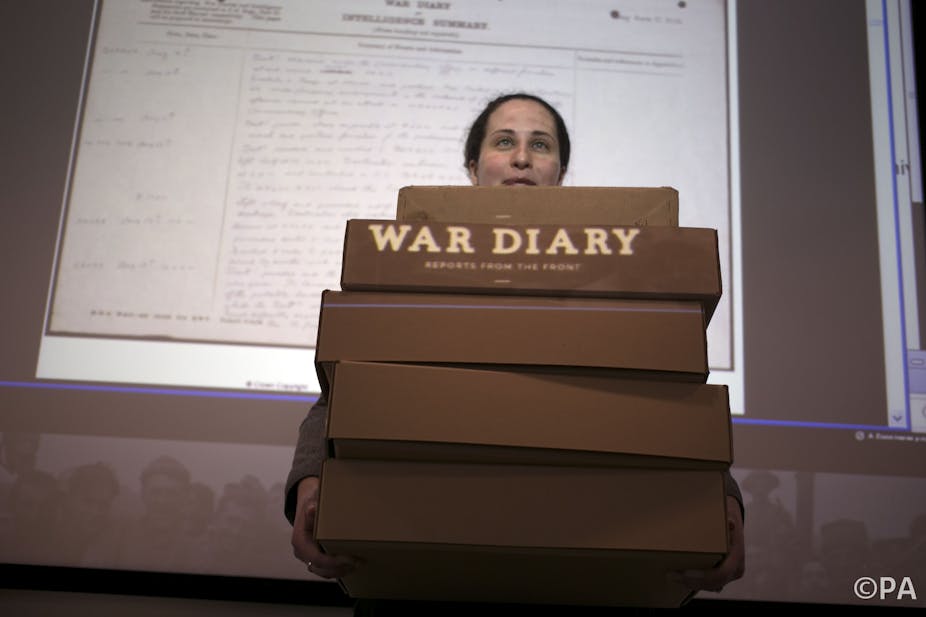

An official history of warfare in the UK in part depends on the systematic collection and collation of sources by the British Army’s Historical Branch. This is the keeper of the British Army’s Operational Records (previously called war diary and commander’s diary) that are recorded monthly by military units. The branch was founded in 1906 and uses these records to provide impartial analysis to support military planning, decisions and accountability.

The ability to quickly mobilise resources and expertise is critical to both live campaigns and the army’s internal, political and public legitimacy. It has been particularly important, for example, during the growing number of inquiries into the conduct of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. This collation of operational records is also fundamental to what kind of history of warfare involving UK forces can be written.

These records are subject to the 1958 Public Records Act, which established the 30-year rule as the time within which all government departments have to review and release their records. This is to ensure the preservation of materials with historical value for the nation in The National Archives (TNA), with those deemed not of value being destroyed or disposed of in other ways. The 30-year buffer protects those potentially subject to embarrassment or danger from the public revelation of their decisions or acts until such a time that events and the documents that pertain to them become less sensitive. This also applies to the records of war.

A perfect storm

The buffer is under pressure. The 2010 Constitutional Reform and Governance Act has led to the 30-year rule being reduced to 20. This means that two years of records are being processed every year from 2013 to meet this requirement in ten years. Yet, the very process of moving from 30 to 20 years is perversely punching holes in the very records in demand by historians.

A perfect storm of Ministry of Defence restructuring, austerity and part privatisation of records management threatens careful selection, collation and preservation, particularly since space is at a premium. The acceleration of the throughput of records (without the doubling of resources) will result in less discrimination in what is retained and what is destroyed.

This is a double whammy. There is a greater risk that valuable records will be lost and a greater chance that sensitive materials will slip through into the public domain. Faster history is not better history. Why not pause the throughput of the last of the paper records to afford proper time to assess, preserve and secure the basis of a full history?

Digital Search

The transition from physical to digital archives coincides with the 2003 Iraq War. Those records declassified and deemed of historical value will reach The National Archives from 2023. By 2026 there will no longer be new paper records being sent to the archive.

This might make records easier to find but something important is lost. The digital file strips away the subliminal context that comes with the finding, filing, handling and searching through the physical file. The mental map of the archive and its contents dissolve.

When libraries adopted microfilm as the standard means of handling newspaper collections, the problem was the same. As Nicholson Baker, US writer and creator of the American Newspaper Repository warned:

If you have a date and a page number you look that one citation up and leave; you’re rarely tempted to spend several hours splashing in the daily contextual marsh.

Without the material context – the content in front and behind each document – the information may be found but the story can be lost. Today’s seductive immediacy and apparent precision of digital search obscures much that could have been found and understood.

Handwritten (and even the typed) documents tend to provide the first drafts of history. This writing is more likely to preserve a stream of consciousness and the thoughts of the writer in the field at the time. The word-processed account militates against the survival of these original thoughts and hides edits made along the way by the author and by others.

Saving paper

Digital records also surpass human-scale management capacities. The complexity and volume of the millions of files, including still images and video, that have flowed out of Iraq and Afghanistan make even the records produced about the Great Wars look oddly out of proportion. How these are managed and how we are to assess which are safe for release and worthy of public interest remains an open question.

Take emails, for example. What proportion of this sticky web of communications will make it into the public domain? And what kind of history is likely to be distilled from what could potentially be millions of documents compared with the writings of wars of the previous century?

From 2026 there will be barely any new paper history of warfare left to emerge. Surely then, the remaining material records of wars yet to be released – the 1991 Gulf War, the Balkans (and indeed all Government paper records) – are worthy of preservation, as the last of their kind?

The history of warfare is at a critical juncture. We need to renew our faith in the paper archive and resist the idea that paper is too fragile a medium to hold our history. We have to save the last of the material wars and ensure that their rich histories are discoverable.