Following the explosion of do-it-yourself music in the 1990s, aspiring DJs and producers have been spoiled rotten. Home studios are increasingly commonplace now that there is such a wealth of affordable equipment to choose from and the process of making music is becoming a social experience rather than a solo adventure.

Where once music lovers hid away alone in a dark bedroom for days and weeks to produce their next demo, new technology is being used to encourage them to work as a team. According to John Richards, lecturer in music, technology and innovation at De Montfort University, today’s electronic music landscape has shifted away from do-it-yourself and towards a “do-it-together” mentality.

Amateur music makers are emerging from their studios and collaborating at workshops, events and live performances. For Richards, this shift began at the turn of the Millenium. “Laptops and PCs became common-or-garden tools that served many domestic functions,” he says. “And this too has extended to mobile devices and tablets. DIT culture looks to make specific time and space for something different in our lives.”

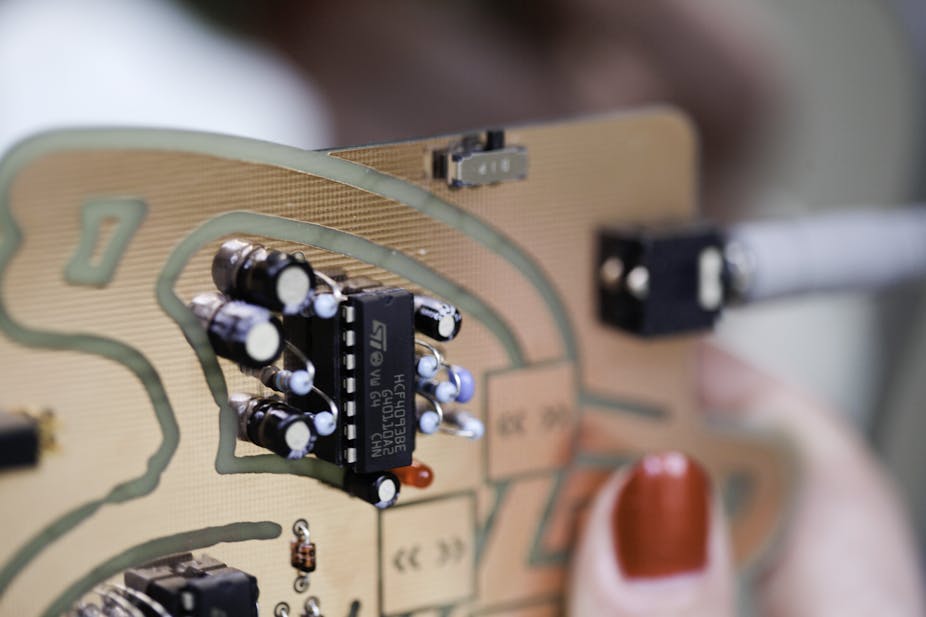

Richards’ own Dirty Electronics workshop is emblematic of this new participatory approach. As part of the Notation and Interpretation Festival at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, he ran a “solder and score” session, where attendees worked together to build an instrument by creating a giant modular system out of circuit boards, wooden boards and metal touch electrodes.

Once built, the participants’ sound devices were connected together and laid out on the floor, resulting in a modular system within which one person’s board fed into the next to produce sound.

“Despite being able to do so many things online, people are driven to get together and make something, often in the name of art,” said Richards. “Perhaps it is more poignant in the field of electronic music, which traditionally – particularly through the recording studio and latterly the laptop – encouraged a more solitary approach.”

Playing your nearest rubbish bin

Real life meetings like these are building on a phenomenon that has been growing for some time. Musicians are using the internet to collaborate.

The popularity of electronic music creation has given rise to the boutique synthesiser and these can be used to produce music with people all over the world.

Synthesisers can either be virtual, online tools or bought as physical hardware from specialised stores. Record labels are picking up on the trend too. Richards is working with one such company, Mute Records, to produce a new hand-held synthesiser in 2014. It’s a very different way of working for the company, said Richards. “It is not recorded music, per se, that is [being] distributed, but a physical sound-generating artifact and an experience.”

Bruno Zamborlin, a PhD student in Arts and Computer Science at Goldsmiths University in London and the IRCAM-Pompidou centre in Paris, specialises in the research of new interfaces for musical expression. He has developed Mogees, a small device which transforms everyday objects into musical instruments.

By attaching it to a variety of objects and surfaces, it converts vibrations into electrical signals, blurring the line between the physical and the digital world. These signals are then sent to a mobile phone which uses the Mogee software application to analyse the vibrations and turn them into musical sounds. So a rubbish bin or a tree can become an instrument in your own personal orchestra. You can then share your sounds with other users online and combine your work into a duet without ever even meeting.

“The most interesting effect of a DIT approach to music technology is the change of focus from the music produced with new instruments to the productions of the instruments themselves,” Zamborlin said, adding that the ability to build your own instruments is a valuable tool for both music enthusiasts and music teaching.